Mystery Surrounding Brightest Cosmic Objects Said Solved

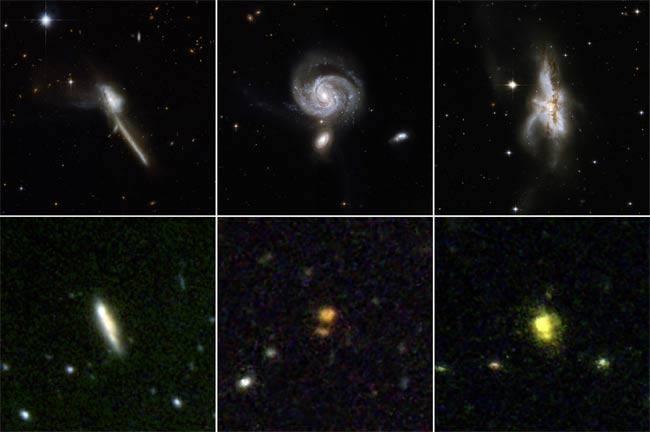

Quasars are regions around giant black holes where matter isgobbled up and light is flung back into space. The origin of these blazingobjects has been unclear, but a new study found they likely form when twomassive galaxies collide.

Not just any large black hole becomes aquasar ? the distinction is reserved for those supermassive black holesthat are growing. As they feed on swirling matter around them, friction andheat release copious amounts of radiation that make quasars some of thebrightest objects in the universe.

So in order to have a quasar, a galaxy must contain asufficient store of mass in its center ready to be eaten by the supermassiveblack hole there. And the best way to get this supply of food concentrated inthe galactic center is a merger between two large, gas-rich galaxies, the studyconfirmed.

This concept was first suggested by University of Hawaiiastronomer David Sanders in 1988. But it wasn't until now that observationalevidence of distant galaxies from the early universe confirms this.

Sanders and a team of astronomers led by Ezequiel Treister,also of the University of Hawaii, combined data from the Hubble,Chandra and Spitzer space telescopes of far-away galaxies and searched forsigns of quasars that were obscured by gas and dust around them. Thetelescopes, which scan the universe in optical, X-ray, and infrared light,respectively, allowed the astronomers to cut through some of the haze.

The astronomers found a sizeable sample of these distanthidden quasars, and calculated how many obscured quasars there were at variousdistances, which represent various epochs in the universe's history, becausethe farther they looked, the longer that light took to reach Earth.

The researchers think that newborn quasars are often hiddenfrom view, but that over time the surrounding material falls into the blackhole, leaving the quasar visible. That would suggest that obscured quasars aremore often farther away ? earlier in time ? but more recently many of them havetransitioned to their visible phase. And their observations confirmed this.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We made a simple model in which every galaxy mergergenerates a quasar that is first obscured and then un-obscured," Treistertold SPACE.com. "The agreement is just remarkable. That does indicate thatpretty much every galaxy merger generates a quasar."

Supermassive black holesare thought to reside in the center of most galaxies, including our own MilkyWay. But many of these have not undergone mergers with other galaxies, and solack enough spare gas waiting to be gobbled. Other galaxies may once havehosted quasars, but the quasar's food ran out and it died down into arelatively sedate central black hole.

The Milky Way doesn't seem to have undergone any majorcollisions with other large galaxies in the past. However, our neighborgalaxy Andromeda is supposed to slam into the Milky Way in the distant future.

"When the Milky Way collides with Andromeda, if at thattime there's enough gas available, that gas will probably end up in the centeraround the black hole, making a quasar," Treister said [more collidinggalaxies images].

The scientists report their findings in the March 26 issueof the journal Science.

- ImageGallery: Spectacular Photos From the Revamped Hubble

- The Strangest Things in Space

- Video Show ? The Black Hole That Made You Possible

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.