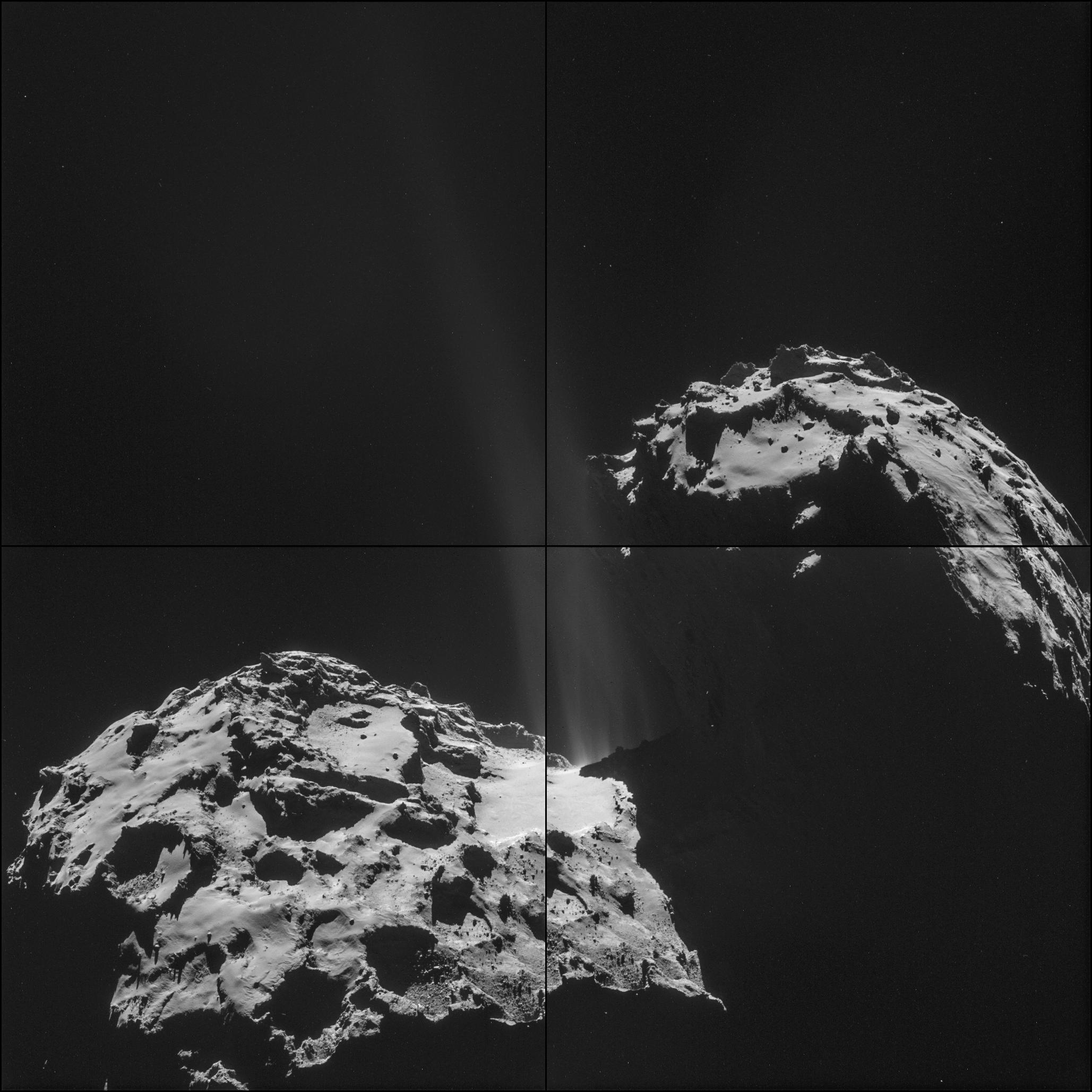

Comet Emits Cosmic Stench, Rosetta Spacecraft Reveals

What does a comet smell like? A pungent cocktail of rotten eggs, horse pee and formaldehyde, apparently.

The European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft caught up with Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Aug. 6 and has been taking measurements of the icy object ever since. The Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis instrument, or ROSINA, has detected some pretty stinky fumes coming from the comet's coma, the fuzzy cloud around its core.

Comet 67P's rotten-egg smell comes from hydrogen sulfide, and the horse-stable odor comes from ammonia. These scents are blended with the fainter almond smell of hydrogen cyanide, the vinegarlike odor of sulphur dioxide and the sweet-smelling scent of carbon disulphide, researchers said.

"If you could smell the comet, you would probably wish that you hadn't," European Space Agency (ESA) officials wrote on the Rosetta spacecraft blog.

However, the density of these foul-smelling sources is low. The coma is mostly made of water and carbon dioxide mixed with carbon monoxide. Still, the rich chemical mix is surprising since the comet was still 250 million miles (400 million kilometers) from the sun when the observations were made.

ESA scientists expect the chemicals to change as 67P draws closer to the sun, and studying the changes will help reveal the chemical composition of the comet.

Because comets are leftovers from the solar system's formation 4.6 billion years ago, learning about 67P's composition could help astronomers gain insight into the conditions present during those early days. The knowledge could also help solve the mystery of how water ended up on Earth — whether it was present from the time of the Earth's formation or if it was delivered later via comets colliding with Earth, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This all makes a scientifically enormously interesting mixture in order to study the origin of our solar system material, the formation of our Earth and the origin of life," ROSINA principal investigator Kathrin Altwegg, of the University of Bern in Switzerland, said in a statement.

The Rosetta mission, which launched in 2004, is gearing up for a big event next month: On Nov. 12, the Rosetta mothership will drop a lander called Philae onto 67P's surface in the first-ever attempt at a soft landing on a comet.

Follow Kelly Dickerson on Twitter. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Kelly Dickerson is a staff writer for Live Science and Space.com. She regularly writes about physics, astronomy and environmental issues, as well as general science topics. Kelly is working on a Master of Arts degree at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism, and has a Bachelor of Science degree and Bachelor of Arts degree from Berry College. Kelly was a competitive swimmer for 13 years, and dabbles in skimboarding and long-distance running.