Why is Pluto not a planet?

It's a question that has sparked debate across the world.

Textbooks had to be rewritten. Members of the public were outraged. Our understanding of the solar system itself was forever changed on Aug. 24, 2006, when researchers at the International Astronomical Union (IAU) voted to reclassify Pluto, changing its status from a planet to a dwarf planet — a relegation that was largely seen as a demotion and which continues to have reverberations to this day.

Today, the debate about Pluto exposes difficulties in the definition of "planet." The IAU defines a planet as a celestial body orbiting the sun, with a nearly spherical appearance, and that has (for the most part) cleared debris from its orbital neighborhood. But even this set of metrics is not universally agreed upon.

Earth, and even Jupiter, have not cleared many asteroids from their orbital regions despite their large size. Moreover, there are small worlds that are circular and that orbit the sun and yet are not considered planets, such as Ceres.

Related: 15 stunning places on Earth that look like they're from another planet

Elizabeth Howell, Ph.D., is a staff writer for the spaceflight channel since 2022 and a contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before that. She has covered space missions all over the solar system and beyond, including New Horizons.

Pluto's so-called demotion from planetary status raises larger issues about how to define any object in the solar system, or even in space more generally. It shows that science cannot, sometimes, slot objects into easy categories. Because if the definition of a planet once again widens, it is unclear how to assess the numerous non-circular objects that circle our sun. This may even put the asteroid belt into question, referring to the huge band of small objects between Mars and Jupiter. Or what happens if a planet is somehow broken up into pieces?

All the same, as the Pluto debate took place almost 20 years ago, many still don't quite understand all the fuss, nor why Pluto was knocked from its planetary position. But the solar system's transformation from nine planets to eight (at least by the standard IAU definition) was a long time in the making and helps encapsulate one of the greatest strengths of science — the ability to alter seemingly steadfast definitions in light of new evidence.

What is a planet, anyway?

The word planet (in English) stretches back to antiquity, deriving from the Greek word "planetes," which means "wandering star." The five classical planets — Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn — are visible to the naked eye and can be seen shifting in strange pathways across the sky compared with the more distant background stars.

After the advent of telescopes, astronomers discovered two new planets, Uranus and Neptune, which are too faint to spot with the naked eye (Note that this definition of "planet" is following the Greco-Roman tradition on which the International Astronomical Union or IAU's community definitions are based. The names of planets vary by culture and the naked-eye planets were observed around the world during antiquity.)

When astronomers discovered Ceres (today considered a dwarf planet), they initially categorized it as a "planet" among scientific communities of the day. But that began to change as further measurements showed it was smaller than other planets ever seen at the time. Eventually, Ceres was lumped into a group of rocky bodies, called "asteroids", of which we now know of hundreds of thousands of these in the asteroid belt alone.

Pluto was found and classified as a planet in 1930 (note the IAU was formed in 1919) when astronomer Clyde Tombaugh of the Lowell Observatory in Arizona compared photographic plates of the sky on separate nights and noticed a tiny dot that drifted back and forth against the backdrop of stars. Right away, the solar system's newest candidate was considered an oddball, however. Its orbit is so eccentric, or far from circular, that it actually gets closer to the sun than Neptune for 20 of its 248-years-long trip. It also is tilted to the ecliptic, which is the plane upon which the other solar system planets orbit.

In 1992, scientists discovered the first Kuiper Belt object, 1992 QB1, a tiny body orbiting out in Pluto's vicinity and beyond the orbit of Neptune. Many more such objects were soon uncovered, revealing a belt of small, frozen worlds similar to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Pluto remained the king of this region, but in July 2005, astronomers found the distant body Eris, which at first was thought to be even larger than Pluto.

A planetary conundrum

Researchers had to ask themselves these questions: If Pluto was a planet, then did that mean Eris was one as well? What about all those other icy objects out in the Kuiper belt, or the littler objects in the asteroid belt? Where exactly was the cut-off line for classifying a body as a planet? A word that had seemed straightforward and simple was suddenly shown to be oddly slippery.

An intense debate followed, with many new proposals for the definition of a planet being offered.

"Every time we think some of us are reaching a consensus, then somebody says something to show very clearly that we're not," Brian Marsden, a member of the IAU Executive Committee in charge of coming up with a new meaning for the word planet, told Space.com in 2005.

A year later, astronomers were no closer to a resolution, and the dilemma hung like a dark cloud over the IAU General Assembly meeting in Prague in 2006. At the conference, researchers endured eight days of contentious arguments, with four different proposals being offered. One controversial suggestion would have brought the total number of planets in the solar system to 12, including Ceres, the largest asteroid, and Pluto's moon Charon.

The suggestion was "a complete mess," astronomer Mike Brown of Caltech, Eris' discoverer, told Space.com.

Near the end of the Prague conference, the 424 astronomers who remained voted to create three new categories for objects in the solar system. From then on, only the worlds Mercury through Neptune would be considered planets. Pluto and its kin — round objects that shared the neighborhood of their orbit with other entities — were henceforth called dwarf planets. All other objects orbiting the sun would be known as small solar system bodies.

The New Horizons mission and the planet debate

A contingent of professionals did not take the decision lightly. "I'm embarrassed for astronomy," Alan Stern, a leader of NASA's New Horizons mission, which flew past Pluto in 2015, told Space.com, adding that less than 5 percent of the world's 10,000 astronomers participated in the vote.

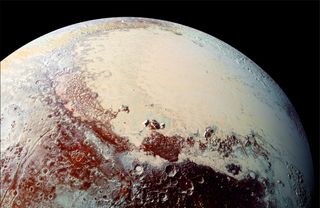

New Horizons was a significant turning point in the planet debate, as its swift flyby by Pluto showed a world that is far more dynamic than anyone imagined. Large mountains, battered craters and signs of liquid flowing upon its surface all point to a world that underwent massive geological change since its formation. On this basis alone, people like Stern have said, Pluto should be considered a planet since it is a dynamic place, a place that is not so static that only micrometeorites disturb its surface.

Views of Charon, Pluto's moon, also show a very dynamic place, including a red cap on its pole that appears to change appearance with the slow seasonal change that far out in the solar system. Notably, Pluto possesses several moons while two established planets, Mercury and Venus, do not. (Numerous asteroids and dwarf planets also have moons, which make the definition of a planet even more complicated.)

Such views are shared by many in the public. In 2014, shortly before the flyby, experts at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, debated different definitions of a planet. Science historian Owen Gingerich, who chaired the IAU's planet-definition committee, asserted that "planet is a culturally defined word that changes over time." But the audience watching the CfA debate overwhelmingly chose a different participant's definition — one that would have brought Pluto back into the planetary fold.

Alternative classification schemes continue to pop up. A 2017 proposal defined a planet as "a round object in space that's smaller than a star." This would make Pluto a planet again, but it would do the same to the Earth's moon as well as many other moons in the solar system, and bring the total number of officially recognized planets up to 110. A year later, Stern, along with planetary scientist David Grinspoon, wrote an opinion article in The Washington Post arguing that the IAU's definition was "hastily drawn" and "flawed" and that astronomers should reconsider their ideas.

Will Pluto ever become a planet again?

Such pleas have fallen on deaf ears so far, and it seems unlikely the IAU will revisit the controversy any time soon. Astrophysicist Ethan Siegel responded to Stern and Grinspoon in Forbes by writing: "The simple fact is that Pluto was misclassified when it was first discovered; it was never on the same footing as the other eight worlds."

Mike Brown also chimed in. "So, hey, Pluto is still not a planet. Actually, never was. We just misunderstood it for 50 years. Now, we know better. Nostalgia for Pluto is really not a very good planet argument, but that's basically all there is. Now, let's get on with reality," Brown wrote on Twitter, where he has embraced his role in the redefinition with the handle @plutokiller.

Why does it matter?

With kids these days (who weren't even born when Pluto was a planet) asking why the definition even matters, astronomers have said that it is no easy answer and we may have to look beyond our solar system in considering what makes a planet and what does not.

More than 5,000 exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system, have been discovered to date and they are showing a huge set of worlds. From "super-Earths" between the size of Earth and Uranus, to "hot Jupiters" orbiting close to suns, to a range of other planetary sizes, the types of planetary environments to consider are changing rapidly.

What this proliferation of planet-forming options shows us is that each solar system may be its own unique environment. While we can say more generally that stars can form planets from collapsing gas and dust in their environment, the individual dynamics that control planet formation are far more complicated. For example, are there multiple stars involved? How much dust is available? Is there a black hole or a supernova blowing the valuable dust and gas away that planets need to grow?

Even if planets are lucky enough to grow up, how they are connected with other planets early in their formation is poorly understood. As worlds interact with each other, their mutual gravities appear to shift planets closer and further from their parent star or in some cases, to fling worlds out of the solar system together.

What this all shows is that our definition of a planet may have to become more situational to account for the number of scenarios in which a world may form. Perhaps planets may be tied to particular formation circumstances or particular zones. All that seems to be known for sure is that as we collect data, planethood and the debate that Pluto has engendered will continue to be debated for quite some time yet.

Additional resources

Learn more about the Kuiper Belt from NASA's Solar System Exploration website. See images of Pluto from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flyby.

References

International Astronomical Union. "Pluto and the Developing Landscape of Our Solar System." https://www.iau.org/public/themes/pluto/

Johns Hopkins Applied Research Laboratory. (2022.) "New Horizons." http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/

NASA. (2019, Dec. 19.) "What is a Planet?" https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/in-depth/

NASA Science Solar System Exploration. "Kuiper Belt." https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/solar-system/kuiper-belt/overview/

Siegel, Ethan. (2018, May 8). "You Won't Like The Consequences Of Making Pluto A Planet Again." Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2018/05/08/you-wont-like-the-consequences-of-making-pluto-a-planet-again/

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace