Welcome Back, Pluto? Planethood Debate Reignites

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The long-simmering argument about Pluto's planethood has just flared up again.

For more than 75 years after its 1930 discovery, Pluto was regarded as our solar system's ninth planet — a distant and frigid oddball, to be sure, but a member of Earth's immediate family nonetheless. Then, in 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) reclassified Pluto as a "dwarf planet," a newly created category that the organization explicitly stressed made Pluto distinct from the eight "true" planets.

A true planet, according to the IAU's newly devised definition, must meet three criteria: It must circle the sun and no other object (so, moons are out); it must be big enough to be rounded into a sphere or spheroid by its own gravity, but not so large that its innards host the fusion reactions that power stars; and it must have "cleared its neighborhood" of other orbiting bodies. [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

Pluto failed at this last hurdle, because its neighborhood — the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune known as the Kuiper Belt — is far from cleared.

Many scientists and Plutophilic members of the public objected strongly to the IAU's decision, on various grounds. For starters, some folks pointed out, the new planet definition rules out anything not orbiting the sun — meaning that the hundreds of billions of exoplanets in our Milky Way galaxy aren't planets at all, at least according to the IAU.

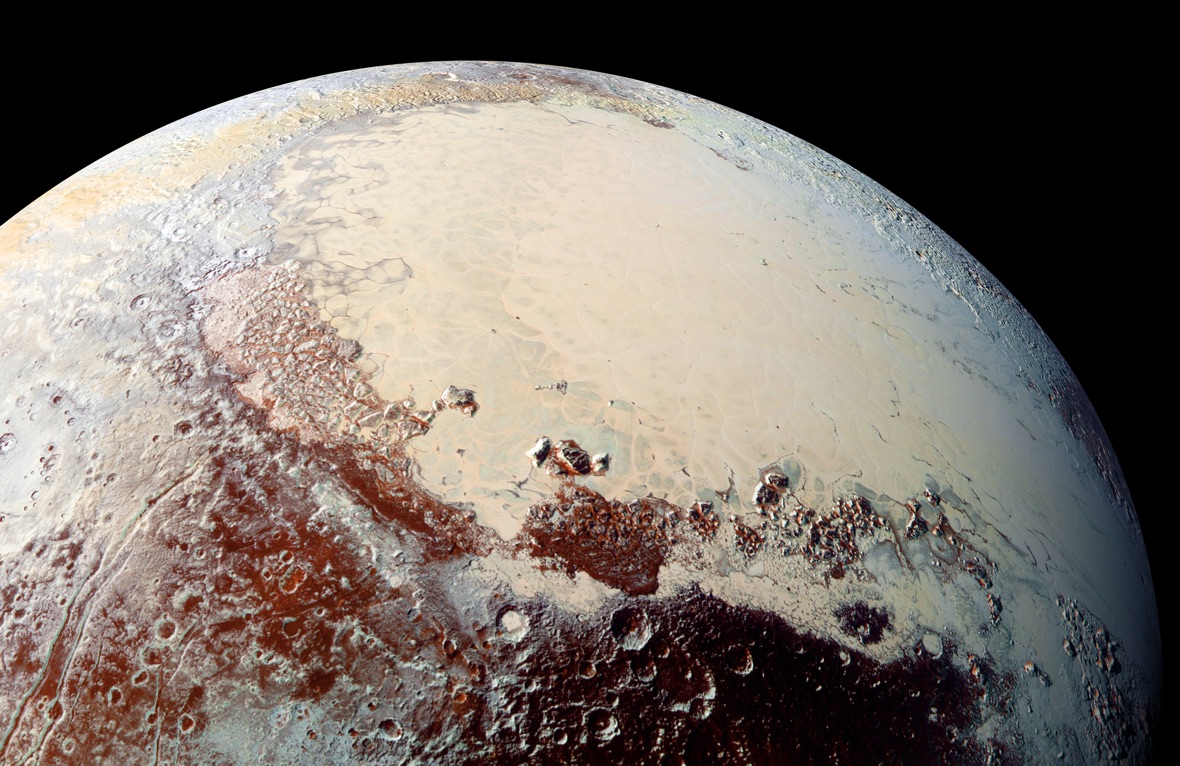

And the "clear your neighborhood" requirement seemed ridiculous to many researchers, including Alan Stern, the principal investigator of NASA's New Horizons mission, which famously flew by Pluto in July 2015. Stern has been a vocal proponent of Pluto's planethood and has argued that the IAU's decision stemmed at least partly from a very nonscientific desire to keep the solar system's planetary stable down to a "manageable" number.

Which brings us to the most recent flare-up. Stern and planetary scientist David Grinspoon have just published a book about the Pluto flyby, called "Chasing New Horizons: Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto" (Picador, 2018). On Monday (May 7), The Washington Post published a "Perspectives" piece the two scientists wrote titled, "Yes, Pluto Is a Planet."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the piece, Grinspoon and Stern took aim at the IAU's "hastily drawn" and "flawed" planet definition, reserving special ire for the "clearing your neighborhood" requirement.

"This criterion is imprecise and leaves many borderline cases, but what's worse is that they chose a definition that discounts the actual physical properties of a potential planet, electing instead to define 'planet' in terms of the other objects that are — or are not — orbiting nearby," the scientists wrote. "This leads to many bizarre and absurd conclusions. For example, it would mean that Earth was not a planet for its first 500 million years of history, because it orbited among a swarm of debris until that time, and also that if you took Earth today and moved it somewhere else, say out to the asteroid belt, it would cease being a planet." [Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

The duo pushed instead for a much simpler "geophysical planet definition," which was presented last spring at a planetary science conference in Texas. And this definition is indeed simple; boiled down, it holds that planets are "round objects in space that are smaller than stars."

Under this definition, Pluto and other dwarf planets, such as Ceres and Eris, are considered planets, as are large moons like Jupiter's Europa, Ganymede, Io and Callisto and Saturn's huge satellite Titan (as well as Earth's own moon). Indeed, the solar system's planet count would easily top 100 if everyone agreed to use the geophysical definition.

But getting such widespread agreement about this, and about Pluto's "official" classification, will be a hard row to hoe. For example, astrophysicist and author Ethan Siegel argued in a piece for Forbes on Tuesday (May 8) that a cosmic object's environmental context is important to understanding the object's nature.

"The simple fact is that Pluto was misclassified when it was first discovered; it was never on the same footing as the other eight worlds. The 2006 move by the IAU was an incomplete attempt to repair that mistake," Siegel wrote.

The geophysical definition, he added, "is a step in the opposite direction: It's a step towards making a larger, more confusing mistake that will render a definition meaningless to the majority of people who use it."

And then there's the pithy take by California Institute of Technology astronomer Mike Brown, whose discovery of outer-solar-system objects helped spark the rethink of Pluto's place in the solar system.

"So, hey, Pluto is still not a planet. Actually, never was. We just misunderstood it for 50 years. Now, we know better. Nostalgia for Pluto is really not a very good planet argument, but that's basically all there is. Now, let's get on with reality," Brown wrote via Twitter, where his handle is @plutokiller.

Will the geophysical planet definition catch on? Will the IAU welcome Pluto back into the "true planet" fold, along with Ceres, Europa, Titan, Earth's moon and many other objects? Who knows? But it seems clear that people will be fighting about this stuff for a long time to come.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.