Pluto's Planet Title Defender: Q & A With Planetary Scientist Alan Stern

After being recognized as the solar system's ninth planet for three-quarters of a century, Pluto was demoted to a newly created category, "dwarf planet," five years ago today (Aug. 24).

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) devised that category in 2006 in response to the discovery of large objects besides Pluto in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune.

To qualify as a full-fledged planet, the IAU decided, an object had to meet the following criteria: It must circle the sun without being some other object's satellite; it must be large enough to be rounded by its own gravity, but not so big that it begins to undergo nuclear fusion like a star; and it must have "cleared its neighborhood" of most other orbiting bodies. [Q & A With 'Pluto Killer' Mike Brown]

Pluto failed to meet the third criterion, since it shares space with other big Kuiper Belt objects. So IAU members at a 2006 meeting voted to strip Pluto of its planethood.

Alan Stern didn't like the move then, and he doesn't like it now. Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., thinks the IAU's new definition of "planet" is flawed and unscientific.

As the fifth anniversary of Pluto's demotion neared, SPACE.com caught up with Stern, who is also principal investigator of NASA's New Horizons mission, which is sending a spacecraft to Pluto for the first time ever.

Stern talked about the IAU's decision, the outer solar system's many dwarf planets and why he's so excited about New Horizons' Pluto visit in 2015.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SPACE.com: How do you feel on the fifth anniversary of Pluto's reclassification? Do you still think it was the wrong move?

Alan Stern: I think the IAU really embarrassed themselves with this. They created a problem for themselves and for astronomy. It [the definition] created an unworkable algorithm for deciding what's a planet and what's not.

After all, it produces patently ridiculous results, so people just move on. I see professional PhD astronomers refer to objects the IAU would not consider planets as planets all the time.

It shouldn't be so difficult to determine what a planet is. When you're watching a science fiction show like "Star Trek" and they show up at some object in space and turn on the viewfinder, the audience and the people in the show know immediately whether it's a planet, or a star, or a comet or an asteroid.

And that's at a moment's notice. They do not need to know things like, "What else is around it? And, let's see, we're going to integrate orbits, we're going to find out if it's cleared its zone, or it might some day, or maybe it could but it didn't." That's making something hard out of something easy, and it reflects poorly on astronomy and astronomers.

SPACE.com: One of your chief objections is the "clearing your neighborhood" stipulation. Under that definition, Earth wouldn't be a planet in some circumstances, right?

Stern: That's an example of what's so ridiculous about it. Suppose that in your mind, you created a solar system exactly like ours, except at each of the orbits of the nine classical planets, you put an Earth. As you go further outward in the solar system, you cross a boundary where Earth is no longer able to clear its zone, because the zone is too big.

It turns out that happens around the orbit of Neptune, maybe Uranus. So you would have nine identical objects, six of which you would call a planet and three of which you would not. They're identical in every respect except where they are. [Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts]

In no other branch of science am I familiar with something that absurd. "We're going to call it a cow, except when it's in a herd." A river is a river, independent of whether there are other rivers nearby. In science, we call things what they are based on their attributes, not what they're next to.

And the IAU definition is even worse, because it produces different categorizations for identical objects, depending on where they are. Get this — Earth at the same distance from the sun [as Pluto] would not be a planet by the IAU’s measure, because Earth can’t clear that zone either. I would say any definition that produces a result where Earth is not a planet under any circumstance is immediately indicted as ridiculous, because one thing we all agree is a planet is planet Earth!

That's crazy. No wonder teachers and students are frustrated, confused, unhappy. It reflects poorly on astronomy, to have something so illogical.

SPACE.com: Why do people care so much about Pluto's status? Why do they get so worked up?

Stern: I think there are several reasons. Some people say it's illogical. Some people say they grew up with it, and they see no reason to change it. Some people say the definition the IAU came up with is flawed. So a lot of people just ignore it. They decide, "The IAU has no police force; I'm going to call what I see as a planet a planet, and those guys can catch up later."

SPACE.com: Does it actually matter what we call these things? Or is it just semantics?

Stern: I think it matters.

In science, we take large numbers of disparate facts and reduce them to see patterns. We use the patterns to reduce the amount of information. It's the reason we name species and genera and families in biology. It's also the reason we have names for certain types of geological features, and so on in other fields. [Infographic: Pluto - A Dwarf Planet Oddity]

We see the patterns, and we make conclusions from those patterns. It's very important. In astronomy, we categorize what a star is, what a galaxy is, what a comet is, et cetera.

My field is called planetary science. It seems to me absurd to be in the position, as planetary scientists, not to understand the basic attributes of those objects after which the field is named.

Basically, we lived in a very naïve world for a very long time, where we only knew of nine planets — terrestrial planets, gas giants, and this one misfit, Pluto. But when we looked in the Kuiper Belt, we found a bunch of Pluto-sized planets.

So it's the terrestrial planets and the giant planets that are the misfits. The IAU treated it in a very unscientific way, saying, "We just won't count those things as planets." And you had some very accomplished astronomers in some cases saying, "We can't have 50 planets. My daughter will never remember the names of all of them."

That's not a very scientific way of going about it, since we have countless numbers of stars, galaxies, asteroids and everything else.

I think the IAU had a wonderful opportunity to actually excite the public about astronomy by saying, "Look, we've discovered something wonderful. There's a third class of planet we didn't know about. There's more of them than anything else." [Meet the Solar System's Dwarf Planets]

But instead of embracing new data and saying, "We learned something new," they retrenched. And retrenched in a way that I think is essentially unforgivable, because it teaches disrespect for science. This new definition, which creates a circumstance where Earths aren't a planet in every circumstance — it just doesn't breed respect for science.

People can look at pictures of objects that obviously look like planets, and they get ruled out because they happen to be near something else — not what they are, but what they're near — again, it breeds a disrespect.

And when you show pictures of scientists voting, it's just awful. Because there are a lot of people in our society who think science is arbitrary and political — that global warming and climate change aren't real, that evolution is just an idea. And when it appears that science is decided by votes, it makes all of science look arbitrary.

SPACE.com: What's the legacy of the decision going to be? Are people going to ignore it and say, "There are thousands of interesting bodies out there — let's just deal with them on their own merits?"

Stern: I think that's what's already taking place. Most planetary scientists aren't even in the IAU. The IAU's made up primarily of people who study galaxies, mostly, and stars. So the members are not experts on planets in most cases.

Moreover, the people who voted at the IAU’s Prague meeting [in 2006] were a very small fraction — I think 4 percent was the number — of the IAU, again most of them not planetary scientists.

Yet, thanks in part to a largely scientifically naive press, the public feels like the IAU is somehow this Supreme Court. But it's almost like you've asked the wrong group to decide. It's as if you went to the wrong type of lawyer. Say this is a technical matter that has to do with financial law, and you went to a divorce lawyer. Well, they're lawyers, yes, but they don't really know the technical details of financial law. Asking the IAU to define planets, when most IAU members aren’t even planetary scientists, is just about as crazy!

SPACE.com: Let's talk about the science a little bit. How has our understanding of the solar system been shaken up by these discoveries in the Kuiper Belt in the last two decades?

Stern: The first big revelation of the Kuiper Belt was, it expanded the scale of the solar system. It's the biggest structure in the planetary region. It dwarfs the region of the giant planets. [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

The second is, it changed our view of what the outer solar system is. The outer solar system now starts just beyond Neptune. And the region a lot of people used to call the outer solar system is now called the giant planet region, or the middle zone.

The third thing it did is that it told us there are very large numbers of planets in the solar system. Easily 90, and probably more like 900. And it showed us that most planets in the solar system are small ones. The small planets, the Chihuahuas if you will, outnumber the German shepherds and the Great Danes 10 or 100 to one.

And the last thing it did is, when you look at the different dwarf planets — you look at Sedna and Eris and Haumea and Makemake — there's a huge degree of diversity between them. That's not as surprising as it might seem, because when you look at the satellites of the giant planets, there's a huge amount of diversity. Io is nothing like Europa, and Titan is nothing like Triton, and none of them are like Enceladus.

But we'd been dealing in planetary science with extremely small-number statistics. We had nine planet examples — apparently four rockies, four giants and one misfit — whereas with the satellites, we had dozens. And with asteroids, we had thousands. With comets, we had hundreds.

The more we explore, the more you start to see lots of diversity in each group. But with the planets, we had so few examples before the Kuiper Belt that you couldn't see the patterns yet. Now we're seeing the patterns.

We just lived in a very limited, data-poor world because of technology until the 1990s. It's like you were a biologist who grew up on a small island, and you thought all lifeforms were the few categories that were on that island. And then you developed the technology to see what was going on on all the other islands and the continents of Earth. And you realized that your original view was hopelessly naïve.

That's what we're finding in planetary science, as a result of not just the Kuiper Belt but also discoveries about extrasolar planets. There are planets that have densities like balsa wood, and planets that are darker than coal, and hot Jupiters and super-Earths. I suspect we're just scratching the surface of the diversity — both in the Kuiper Belt and around other stars.

SPACE.com: What is New Horizons going to teach us about Pluto and the outer solar system that we don't know now?

Stern: If I knew, then I wouldn't have to go, now would I? [laughs.] This is the lesson of planetary exploration: Every time we go to a new kind of object and see it up close, we really get blown away.

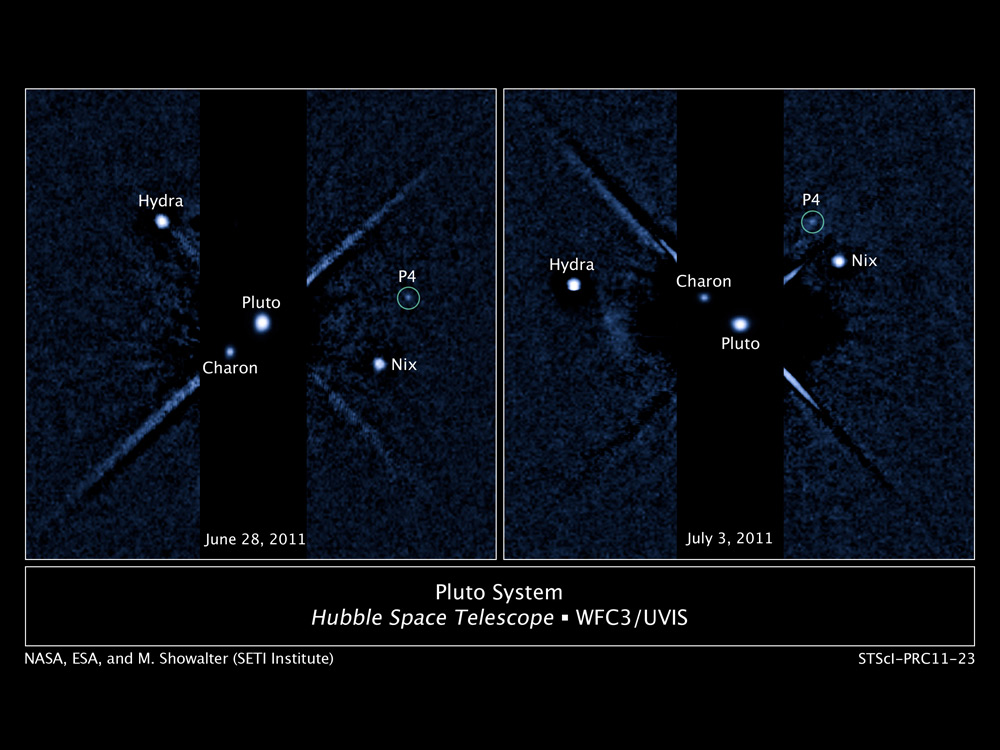

Pluto is the prototype of the dwarf planets. And each time we look at it with a new technology, which is hard to do because it's so far away, we learn something amazing. Like, the atmosphere forms and collapses every orbit. Or this tiny little planet already has four moons, and by the way all bets are off how many more moons we can't see because it's too far away.

We know about polar caps on Pluto. We know it's got multiple different snows on its surface. Nitrogen snows there, methane snows there, carbon monoxide snows there. Just the few things we already see from a distance are crazy. Wait until we get up close with the spectacular set of cameras, spectrometers and other instruments New Horizons is carrying!

That's why I don't make bets about what we’ll find, because we're going to a completely new class of object, and we're going to go right up close. It's going to blow our doors off.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.