Meet the Solar System's Dwarf Planets

For three-quarters of a century, schoolkids learned that our solar system has nine planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto.

But things changed five years ago. On Aug. 24, 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) struck Pluto from the list, demoting it to the newly created category of "dwarf planet." The move was spurred by the discovery of multiple large bodies orbiting even farther from the sun than distant Pluto — particularly an object called Eris, which appeared to be bigger than Pluto.

As a result, the IAU came up with a new definition of "planet": A body that circles the sun without being some other object's satellite, is large enough to be rounded by its own gravity (but not so big that it begins to undergo nuclear fusion, like a star) and has "cleared its neighborhood" of most other orbiting bodies.

Since Pluto shares orbital space with lots of other objects out in the Kuiper Belt — the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune — it didn't make the cut. So Pluto was newly classified as a dwarf planet, which tend to be smaller than "true" planets and fall short on the "clearing your neighborhood" criterion.

Although hundreds, or perhaps thousands, more solar system bodies may eventually join the list, the IAU officially recognizes just five dwarf planets at the moment. Here's a brief tour of all five: Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake and Ceres.

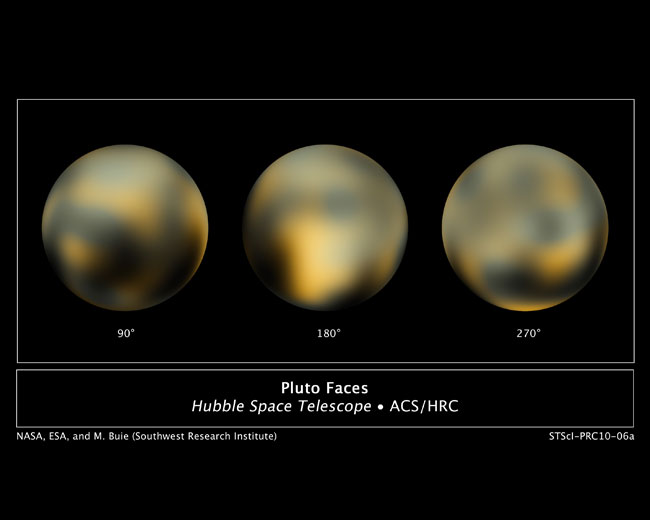

Pluto: The demoted former planet

Pluto was discovered by American Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. It's about 1,455 miles (2,352 kilometers) across — less than 20 percent as big as our planet. And Pluto is just 0.2 percent as massive as Earth.

Pluto has an extremely elliptical orbit that's not in the same plane as the eight official planets' orbits. On average, the dwarf planet cruises around the sun at a distance of 3.65 billion miles (5.87 billion km), taking 248 years to complete one circuit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Because it's so far from the sun, Pluto is one of the coldest places in the solar system, with surface temperatures hovering around minus 375 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 225 degrees Celsius).

Pluto has four known moons: Charon, Nix, Hydra and a newly discovered tiny satellite currently called P4. While Nix, Hydra and P4 are relatively small, Charon is about half as big as Pluto. Because of Charon's size, some astronomers regard Pluto and Charon as a double dwarf planet, or binary system.

Eris: The troublemaker

Caltech astronomer Mike Brown led the team that discovered Eris in 2005. The find spurred the IAU to strip Pluto of its planethood and create the "dwarf planet" category a year later.

That decision remains controversial to this day, making Eris' name quite fitting: Eris is the Greek goddess of discord and strife, who stirred up jealousy and envy among the goddesses, leading to the Trojan War. Eris has one known moon, Dysnomia.

Eris is virtually the same size as Pluto, but it's about 25 percent more massive, suggesting that Eris contains considerably more rock (and less ice) than its Kuiper Belt neighbor. Like Pluto, Eris has a highly elliptical orbit. But Eris is even more far-flung, orbiting the sun at an average distance of about 6.3 billion miles (10.1 billion km). It takes Eris 557 years to complete one lap around the sun.

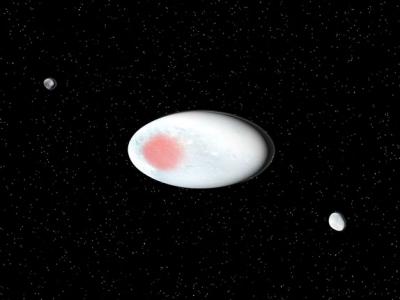

Haumea: The oddball

Haumea, a Kuiper Belt denizen orbiting slightly beyond Pluto, was discovered by Brown and his team in late 2004. It's one of the weirdest objects in the solar system.

Haumea measures about 1,200 miles (1,931 km) across, making it nearly as wide as Pluto. But Haumea is just one-third as massive as Pluto, partly because it's not spherical. Rather, Haumea is shaped like a giant American football.

The dwarf planet also completes one full rotation in less than four hours, making it one of the fastest-spinning bodies in the solar system. This super-charged spin is responsible for Haumea's oblong shape, pushing the dwarf planet outward substantially at the equator. Haumea makes one complete lap around the sun every 283 years.

Haumea has two known moons, Hi'iaka and Namaka.

Mysterious Makemake

Brown's team also discovered Makemake, spotting the dwarf planet in 2005. Astronomers aren't sure of Makemake's exact size, but the dwarf planet is thought to be about three-quarters as big as Pluto. It's therefore likely the third-largest dwarf planet, after Eris and Pluto.

Makemake orbits the sun from slightly farther away than Pluto, at an average distance of 4.26 billion miles (6.85 billion km), and completes an orbit every 310 years or so.

Makemake is the second-brightest Kuiper Belt object (after Pluto) and can be seen with a high-end amateur telescope, according to the IAU.

Ceres: Queen of the asteroid belt

Ceres is the only dwarf planet not found in the freezing cold, faraway Kuiper Belt. Rather, it orbits in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, completing one lap around the sun every 4.6 years.

Ceres is by far the largest object in the asteroid belt, containing about one-third of the belt's mass. However, at 590 miles (950 km) across, it is the smallest known dwarf planet.

Because it's so much closer to Earth than the other dwarf planets, Ceres was discovered far earlier. Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi spotted it first, on Jan. 1, 1801. For the next half-century, many astronomers regarded Ceres as a true planet. That changed when it became apparent that Ceres was just one of many bodies hurtling through space in the asteroid belt.

These days, most astronomers regard Ceres as a protoplanet, saying it likely would have continued growing into a full-fledged rocky planet like Earth or Mars if Jupiter hadn't shaken up the asteroid belt long ago.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.