When is October's partial solar eclipse and who can see it?

Just before Halloween 2022, the sun will appear as if a monstrous bite has been taken from it as the moon's shadow falls on parts of the Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

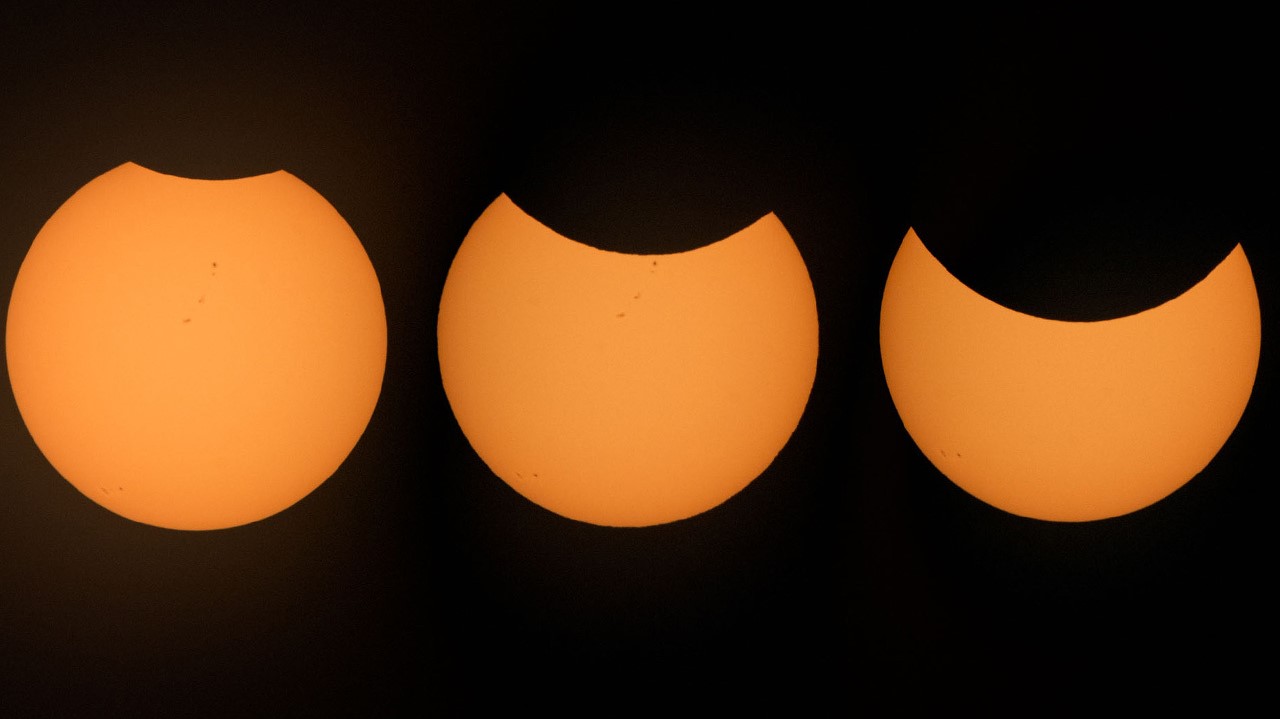

On Tuesday, Oct. 25, 2022, just six days before Halloween the moon will pass in front of the sun creating a partial solar eclipse. The sun will appear as if a huge bite has been taken from it depending on where observers are located across the globe.

The partial eclipse will be visible in the northern hemisphere in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Guernsey in the United Kingdom and will be at its most extreme in the north pole and Russia.

Unfortunately, this partial solar eclipse on Oct. 25 won't be visible in the U.S.

Article continues belowRelated: Solar eclipse guide 2022: When, where & how to see them

Occurring between around 5 a.m. and 9 a.m. EDT (0900-1300 GMT) about 82% of the sun's disk will be obscured by the moon's shadow at the event's maximum — known as the point of central eclipse.

During this particular eclipse nowhere on Earth will experience a total solar eclipse. This is because during the Oct. 25 eclipse the moon and the sun will not be perfectly aligned and as a result, the moon will not completely cover the sun. Instead, the sun will appear to take a crescent shape, almost as if a bite has been taken out of it.

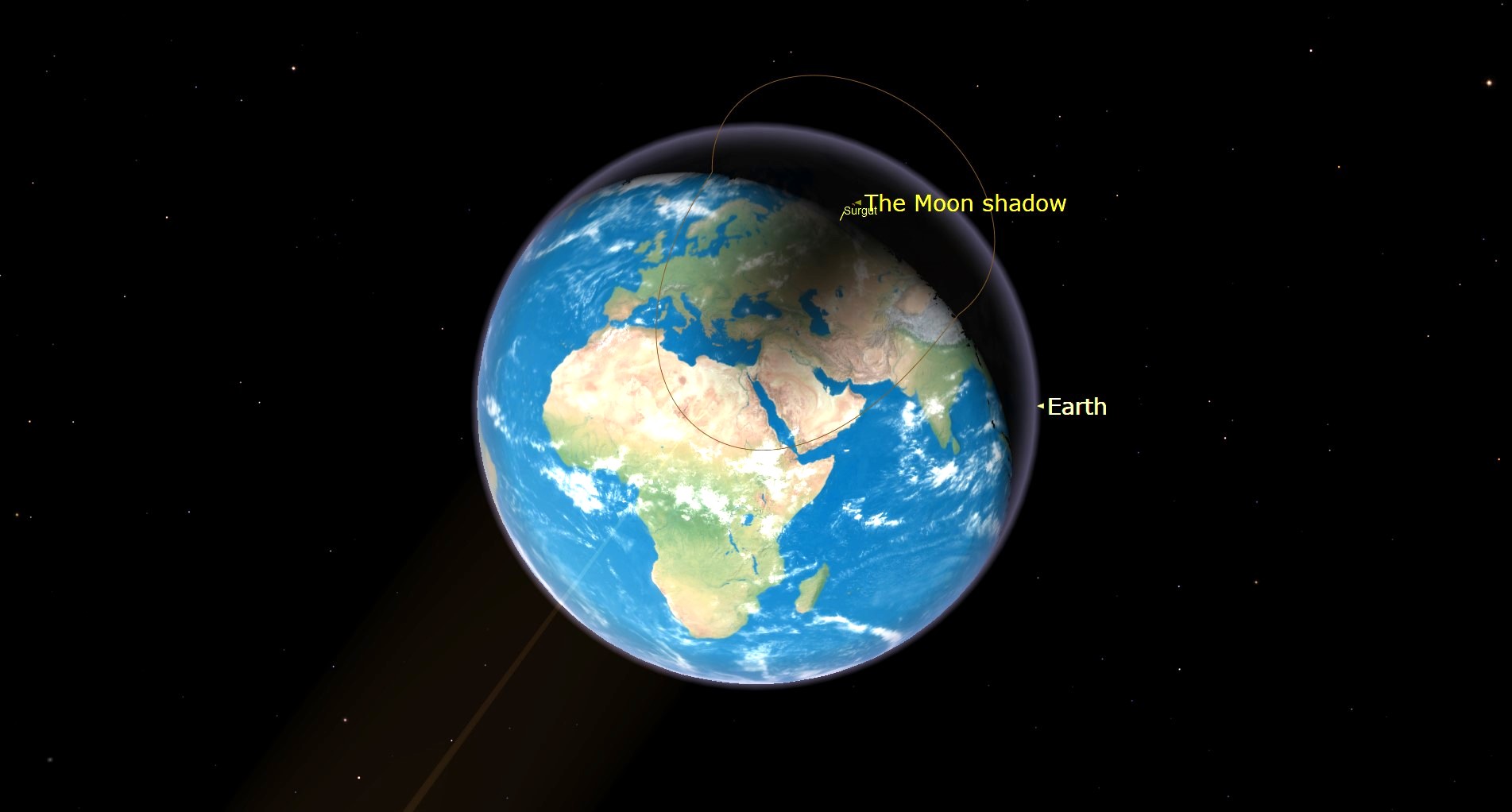

Eclipses happen when the moon passes between the Earth and the sun and casts a shadow on part of the planet either fully or partially blocking the light from the sun. Solar eclipses are never visible across the entire planet because the moon is much smaller than the Earth and its shadow is only a few hundred miles wide.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The point of central eclipse where any eclipse is at its maximum is the point on Earth where an imaginary line connecting the centers of the sun and the moon meets our planet's surface. Observers from this point see the moon directly centered on the middle of the sun.

This point isn't fixed during an eclipse, however. As the moon continues in its orbit its shadow sweeps across the planet at between 1,000 and 5,000 miles per hour taking the point of central eclipse with it.

As a total eclipse proceeds, the point of central eclipse moves across the surface of Earth from west to east. During a partial eclipse, like the one at the end of October, this point either passes above the north pole or below the south pole and doesn't cross the Earth's surface.

That means only the edge of the moon's shadow falls on Earth explaining why the sun doesn't get completely eclipsed.

On Oct. 25 the point of central eclipse will pass over the north pole where 82% of the sun will be eclipsed. From Russia up to 80% of the sun will be eclipsed, this proportion drops to 70% in China, 63% in Norway, and 62% in Finland.

NEVER look at the sun with binoculars, a telescope or your unaided eye without special protection. Astrophotographers and astronomers use special filters to safely observe the sun during solar eclipses or other sun phenomena. Here's our guide on how to observe the sun safely.

Regular sunglasses are not sufficient to use while observing the sun. Observers hoping to view the eclipse should use solar viewing or eclipse glasses. If these aren't available another, indirect viewing method such as using a pinhole projector to project sunlight on a surface.

Looking to photograph the partial solar eclipse? Our How to photograph a solar eclipse explains what it takes to capture one of nature's most spectacular sights.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.