Stunning images from Very Large Telescope capture unique views of planet formation

"This is really a shift in our field of study."

Stunning images captured by the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile reveal unique insights into planet formation around young stars.

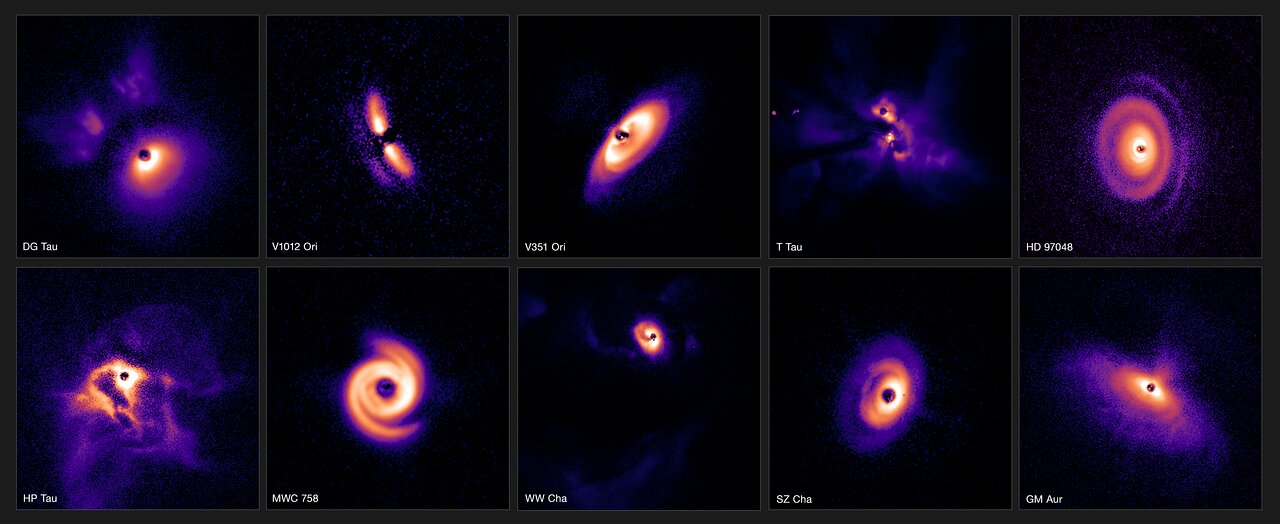

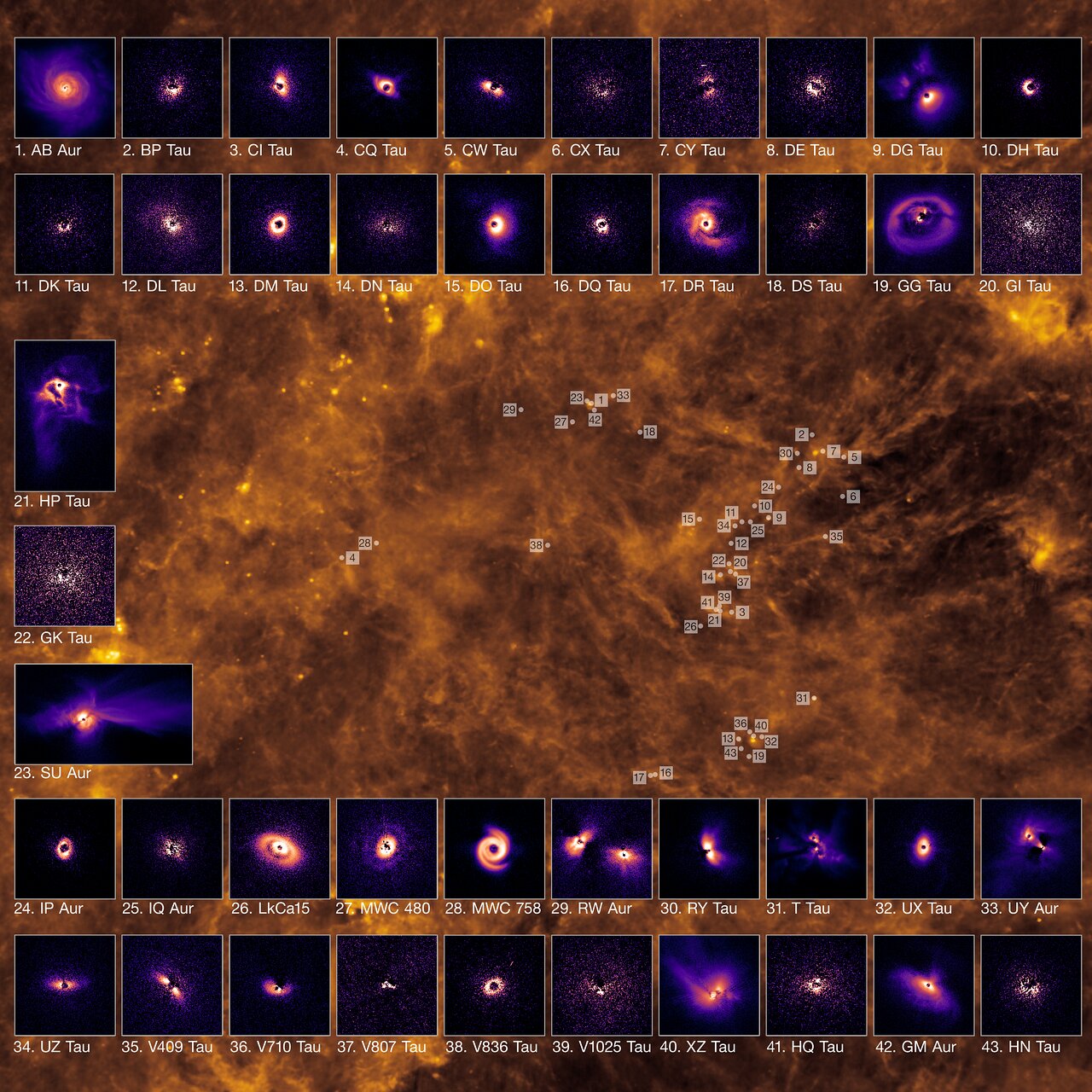

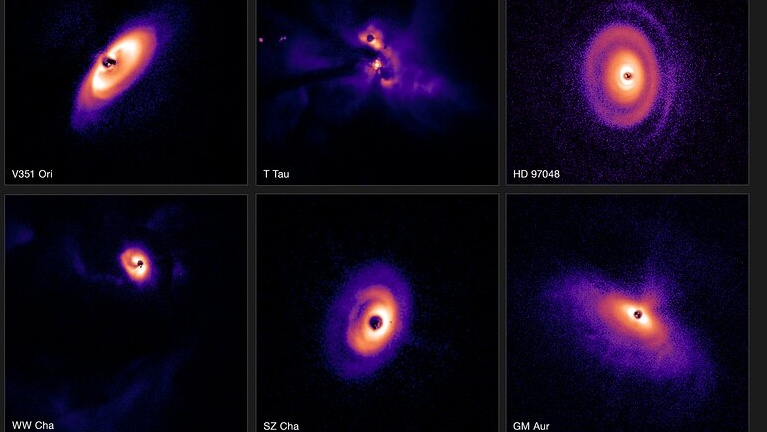

In these portraits, emerging planet systems look more like miniature galaxies rather than disks of debris. The figures showcase clearly defined spiral arms arising from thick dust. Others exhibit less-defined clouds of luminescent matter. For astronomers, these observations present a unique opportunity to study how planets are born. The collection of images, captured by one of the world's most powerful telescopes, is one of the largest of its kind, framing more than 80 young stars and their planet-forming disks.

Related: A baby star's planet-forming disk has 3 times more water than all of Earth's oceans

"This is really a shift in our field of study," Christian Ginski, a lecturer at the University of Galway in Ireland and lead author of three papers detailing the observations, said in a statement. "We've gone from the intense study of individual star systems to this huge overview of entire star-forming regions."

The young stars and their fledgling planets come from three major star-forming regions in the Milky Way galaxy. Some live in either the Taurus or Chameleon I gas clouds, both of which are located some 600 light-years from Earth, and others hail from the somewhat more distant Orion gas cloud about 1,600 light-years away.

The researchers found a wide variety of planet-forming disks that displayed significant differences based on which site they came from. In the Orion cloud, for instance, the astronomers observed groups of two or more stars surrounded only by faint planet-forming disks. Some of the most massive stars in the region had oddly shaped disks, suggesting a presence of very large planets that distort their respective disks with their enormous gravitational pulls.

"Some of these disks show huge spiral arms, presumably driven by the intricate ballet of orbiting planets," Ginski said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Others in the dataset feature rings and large cavities, most likely carved out by forming planets. Still others are smooth and seemingly inactive.

More than 5,000 exoplanets, planets orbiting other stars than the sun, have been discovered by telescopes in space and on Earth since the 1990s. Some of the uncovered planetary systems look completely different from our solar system, and astronomers are therefore still trying to figure out what factors influence the outcomes of planet-forming alchemy. To observe these processes, however, is a difficult task. Regions where stars form are not only far away, but also usually obscured with dust.

To produce the latest collection of images, the astronomers used the VLT's Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet Research instrument (SPHERE), which holds a powerful adaptive optics system that can correct for blurring caused by Earth's atmosphere and produce sharper images. The researchers were thus able to image stars only half as massive as the sun, which most other instruments cannot do, according to the statement. Additional observations taken with the VLT's spectrograph X-shooter and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array provided information about the mass of the stars hosting the imaged planets as well as the amount of surrounding dust.

The researchers hope that, in the future, when the new Extremely Large Telescope comes online in Chile, they will be able to obtain more detailed images, perhaps detecting even small, rocky planets in inner regions of the emerging planetary systems.

Three papers describing the observations were published on Tuesday, March 5, in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics (here, here and here).

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.