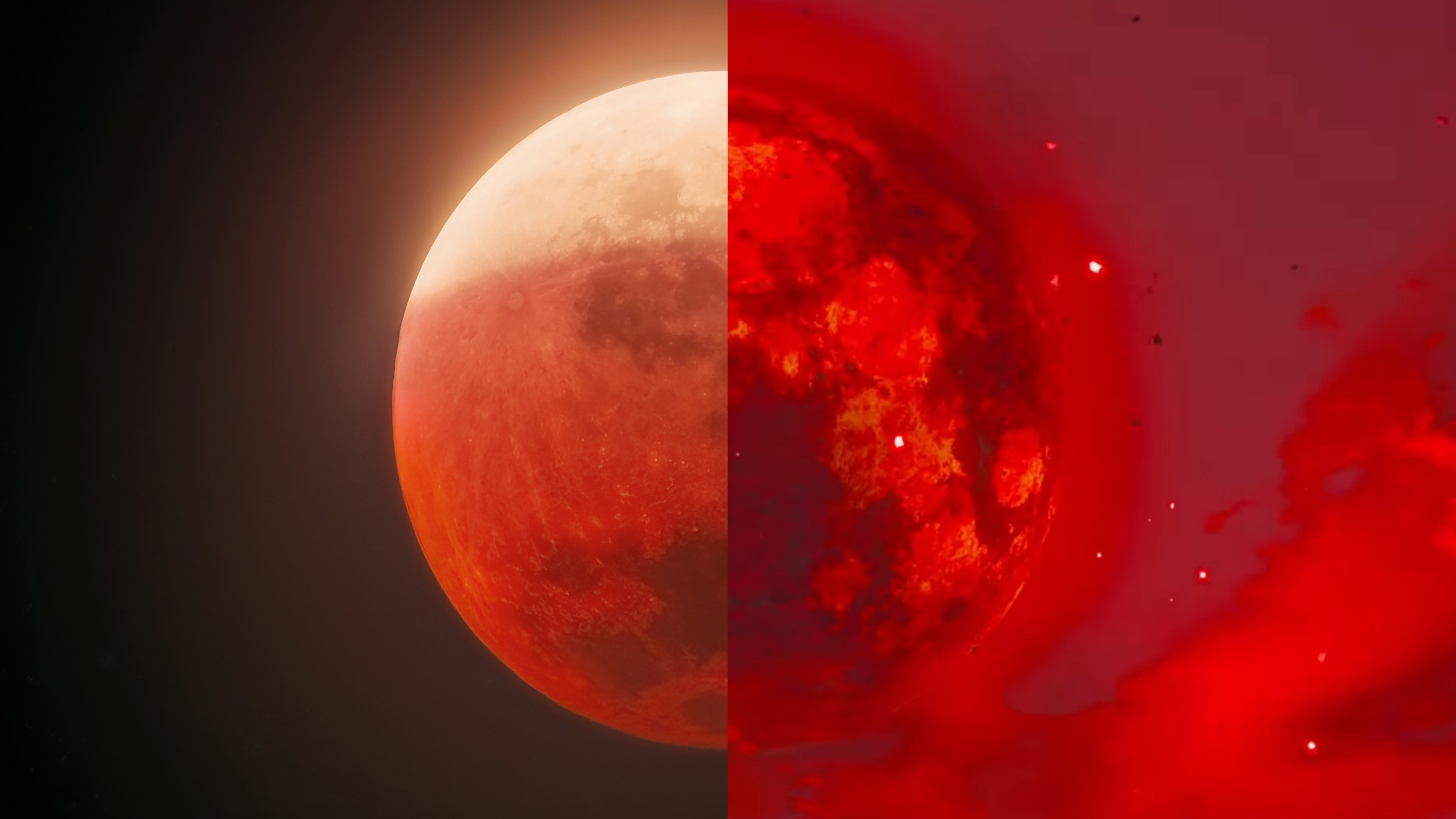

A baby star's planet-forming disk has 3 times more water than all of Earth's oceans

"I had never imagined that we could capture an image of oceans of water vapor in the same region where a planet is likely forming."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers have discovered that a planet-birthing disk of gas and dust that surrounds an infant star is drenched with enough water to fill Earth's oceans three times over.

Water, a key element needed to form and sustain life as we know it, has always been considered to play an important role in forming planets. This is the first time that astronomers have been able to map the distribution of water in a cool, stable disk of gas, or "protoplanetary disk," that is ideal for planet formation.

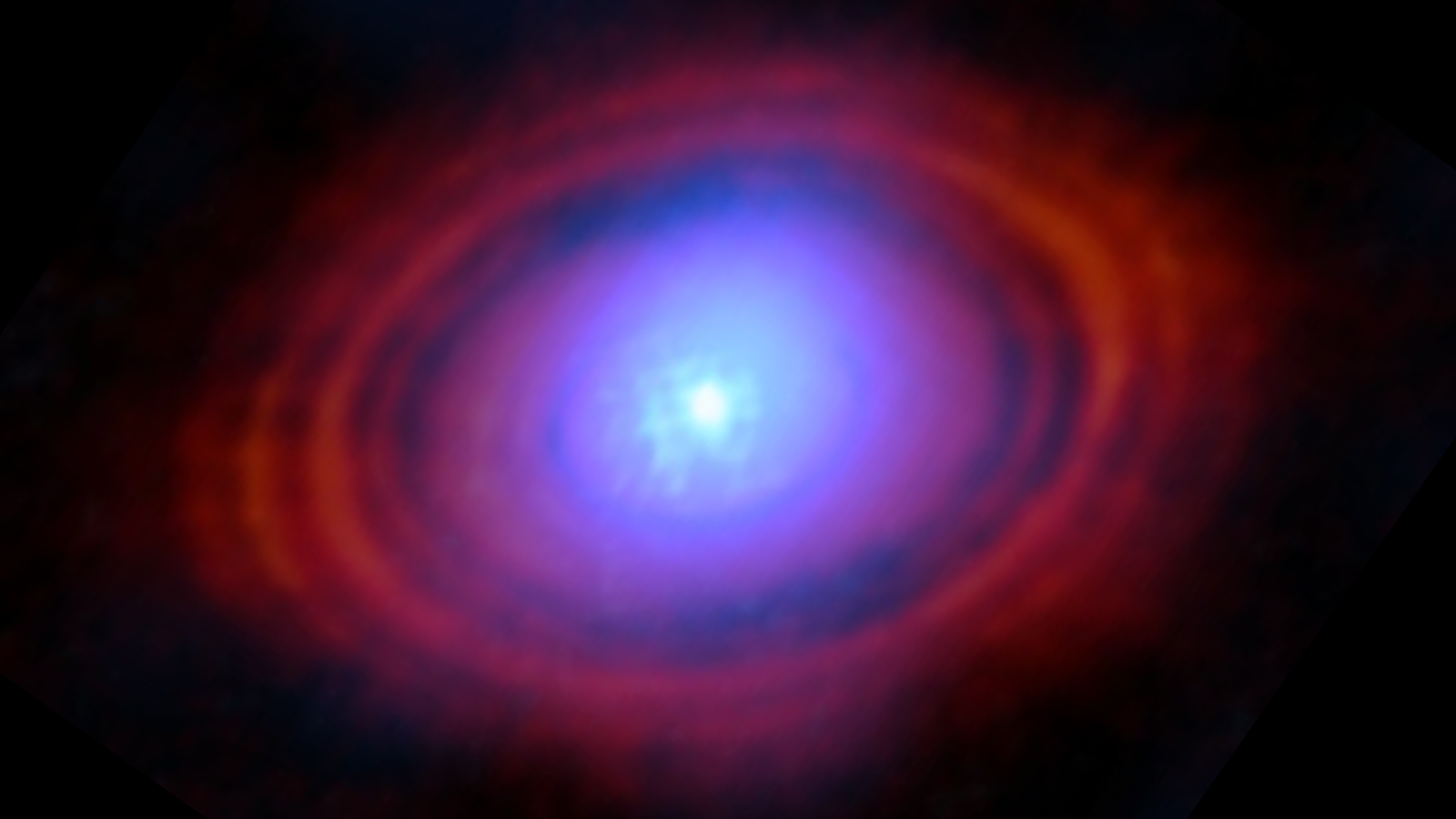

The team behind the breakthrough used the Atacama Large Millimeter/ submillimeter Array (ALMA) to zoom in on water vapor locked up in gas and dust within a protoplanetary disk surrounding the sun-like star HL Tauri, located 450 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Taurus.

"I had never imagined that we could capture an image of oceans of water vapor in the same region where a planet is likely forming," Stefano Facchini research leader and an astronomer at the University of Milan, said in a statement. "Our results show how the presence of water may influence the development of a planetary system, just like it did some 4.5 billion years ago in our own solar system."

Related: James Webb Space Telescope bites cosmic burger to create 1st ice map of planet-forming disk

ALMA gets into the groove around HL Tauri

HL Tauri is part of one of the largest and closest star-forming regions to Earth called the Taurus Molecular cloud, which contains a stellar nursery of hundreds of newborn stars called T Tauri stars. ALMA's sensitivity allowed astronomers to determine the distribution of water in different regions of the HL Tauri disk.

The most significant volume of water in the disk was found in a curved gap that scientists have known about for some time. Ring-shaped grooves in the disk are thought to be carved out as forming planets orbit young stars, gathering mass like a snowball rolling down a hill. Finding water in one of these grooves suggests it is being accrued by budding planets. If true, that water would've impacted their chemical compositions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our recent images reveal a substantial quantity of water vapor at a range of distances from the star that includes a gap where a planet could potentially be forming at the present time," Facchini added.

Not only does this discovery mark an important development in our understanding of planet formation, but it also represents quite an achievement for ALMA. Distinguishing water at such incredible distances is made pretty tricky for ground-based telescopes due to the obscuring effects of vapor in Earth's atmosphere.

ALMA is comprised of an array of telescope antennas located in the Atacama Desert region of Northern Chile. At an elevation of 16,400 feet (4,999 meters), ALMA lives high in the dry atmosphere of Chile, minimizing the effect water vapor has on its observations.

"To date, ALMA is the only facility able to spatially resolve water in a cool planet-forming disk," Wouter Vlemmings, team member and a professor at Chalmers University of Technology, said in the statement.

Astronomers may soon be able to see this planet-forming disk in even greater detail. Not only is ALMA undergoing upgrades, but work is underway in Chile on the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). Both of these instruments could soon use their "high and dry" status to help astronomers better understand the role of water in planet formation.

"It is truly remarkable that we can not only detect but also capture detailed images and spatially resolve water vapor at a distance of 450 light-years from us," team member and University of Bologna astronomer Leonardo Testi said.

The team's research was published on Thursday (Feb. 29) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.