James Webb Space Telescope gazes into a galactic garden of budding stars (image)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

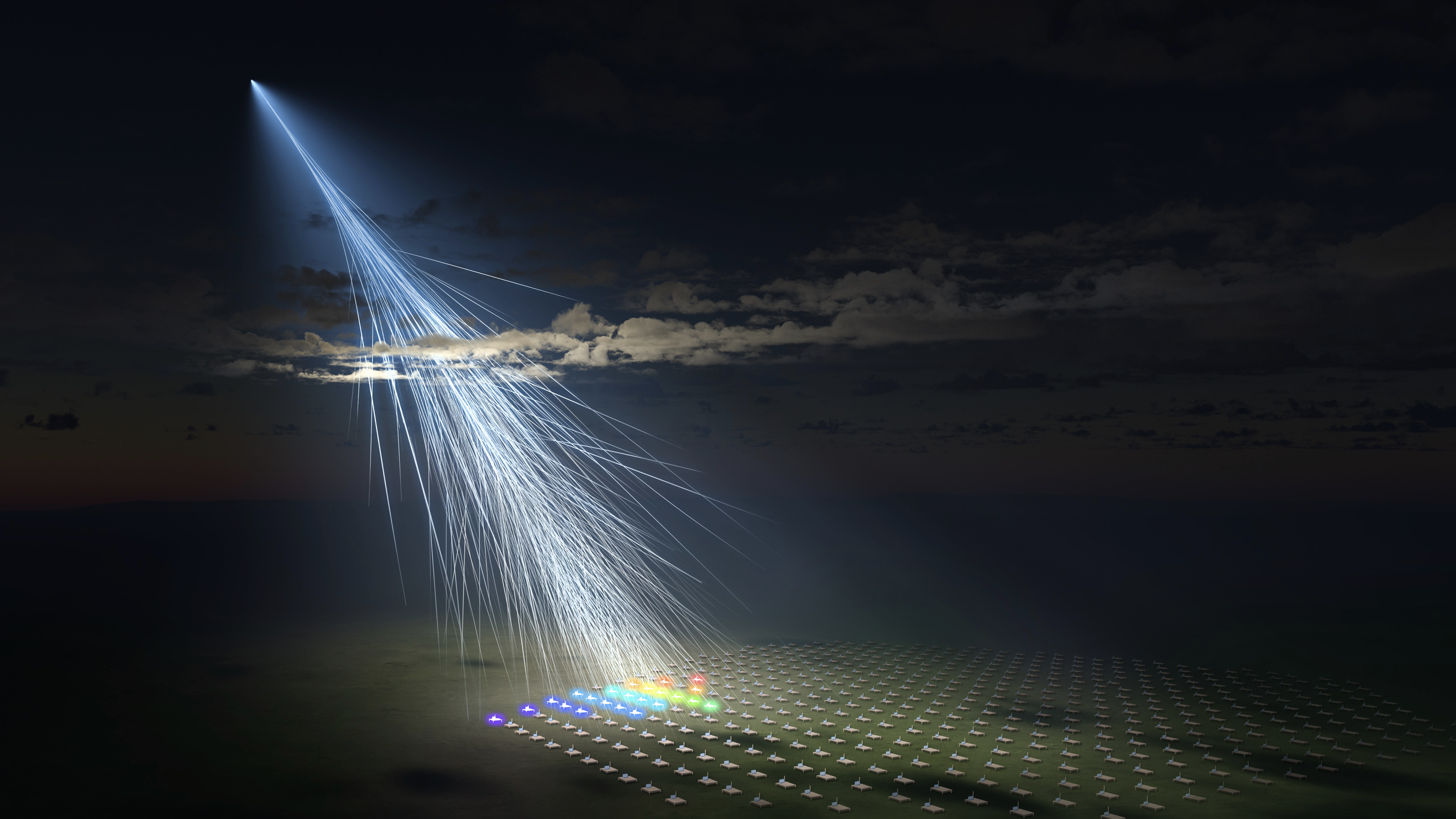

This stunning spiral isn’t a gateway to the abyss. It’s the galaxy M83, as seen through the eyes of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). More specifically, the spaceborne observatory captured this image by tapping into one of its powerful infrared devices, the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

Also known as NGC 5236, M83 is a barred spiral galaxy located about 15 million light-years from us. It's of particular interest to astronomers trying to learn more about star formation. The James Webb Space Telescope's MIRI is their current tool of choice in that quest because, as its name suggests, it observes the universe through infrared wavelengths between 5,000 and 28,000 nanometers. (By comparison, visible light, or the light human eyes are built to see, has wavelengths between 380 and 750 nanometers.)

Related: James Webb Space Telescope detects quartz crystals in an exoplanet's atmosphere

In the image, bright blue regions in the middle indicate areas of dense stars in M83’s galactic center. The bright yellow tendrils spindling out indicate stellar nurseries, or regions where large batches of new stars are actively forming. And the orange-red splashes mark regions rich in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are carbon-based compounds that MIRI’s wavelengths are ideal for detecting.

Astronomers turned MIRI onto M83 as part of the Feedback in Emerging extragalactic Star clusters (FEAST) program. FEAST observations have the goal of understanding how star formation is linked to stellar feedback in galaxies. Stellar feedback refers to the process in which stars eject matter and energy as they form.

By learning more about this relationship, astronomers can hone their models to better decode how stars are born and how they grow. FEAST will include observations of six total galaxies — and previously, FEAST astronomers turned JWST onto M51.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.