Venus Has Wild Climate Shifts and the Secret May Be In Its Clouds

The planet's reflectivity may be the key.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

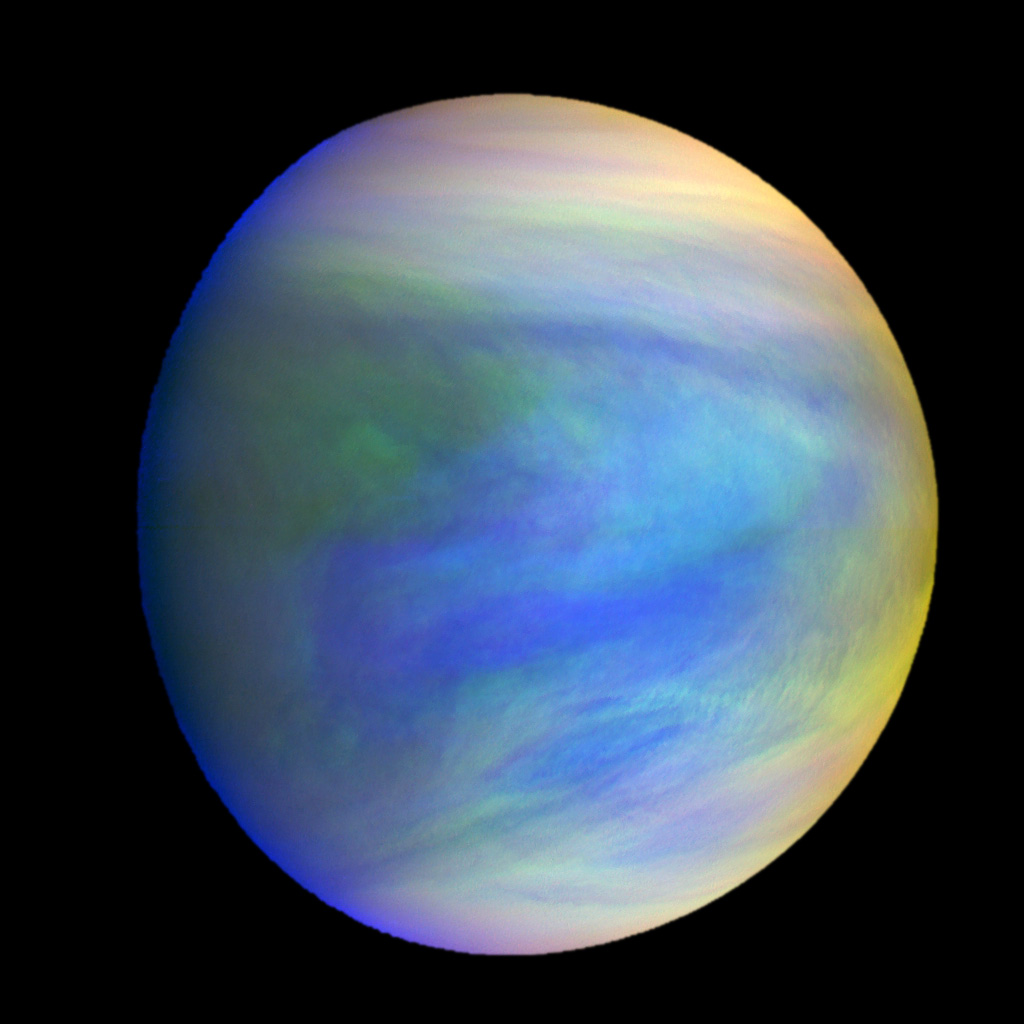

Venus, long billed as Earth's much hotter twin, holds many mysteries within the thick envelope of clouds that surround it — which may also be responsible for the planet's dramatic climate changes.

A new study on a decade of ultraviolet observations of Venus from 2006 to 2017, showed that the planet's reflection of ultraviolet light decreased by half before shooting back up again, researchers said.This change resulted in large variations in the amount of solar energy absorbed by Venus' clouds and the circulation in its atmosphere, causing the changes in the planet's climate, they added.

"Current climate changes on Venus have not been considered before," Yeon Joo Lee, a researcher at the Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics at the Technical University of Berlin, and lead author of the study, told Space.com. "Moreover, the level of UV-albedo [ reflectivity] variations is significantly large, so sufficient to affect atmospheric dynamics."

Article continues belowRelated: How Venus Turned Into Hell, and How the Earth Is Next

Researchers combined observations from Europe's Venus Express mission, Japan's Akatsuki Venus orbiter, NASA's Messenger spacecraft (which flew by Venus on the way to Mercury) and the Hubble Space Telescope for the study.

The weather on Venus, like that of the Earth, is affected by solar radiation and the changes in the reflection of its surrounding clouds. But unlike Earth, Venus' clouds are made up of sulfuric acid and contain dark patches that scientists have referred to as "unknown absorbers" as they absorb most of the heat and ultraviolet light emitted by the sun.

The new study suggests that these absorbers may be what is causing these changes in Venus' climate, although the team of scientists believe that the only way to know for sure is through further observations.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"At least one more decade [[of] observation. That will cover one more solar-activity cycle, and we will be able to find out whether or not this change is cyclic," Lee said.

The weather on the planet is already quite extreme, with temperatures reaching 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsuis), and winds sweeping across Venus' surface at a speed of 450 m.p.h. (724 kilometers/h).

If further observations were to prove that solar activity is connected to this change in climate, then it could be applied to all other planets with aerosols, solid or liquid particles that reflect sunlight, such as Earth and Titan, according to Lee. However, the degree of change would be different in each one.

Lee said she is developing plans for more research on the unknown absorbers in Venus' clouds, adding that a future mission to Venus could help researchers gain a better understanding of the planet's changing climate.

- 10 Weirdest Facts About Planet Venus

- Can Venus Teach Us to Take Climate Change Seriously?

- The Strange Case of Missing Lightning at Venus

Follow Passant Rabie on Twitter @passantrabie. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Passant Rabie is an award-winning journalist from Cairo, Egypt. Rabie moved to New York to pursue a master's degree in science journalism at New York University. She developed a strong passion for all things space, and guiding readers through the mysteries of the local universe. Rabie covers ongoing missions to distant planets and beyond, and breaks down recent discoveries in the world of astrophysics and the latest in ongoing space news. Prior to moving to New York, she spent years writing for independent media outlets across the Middle East and aims to produce accurate coverage of science stories within a regional context.