Future moon astronauts may 3D-print their supplies using lunar minerals

They could make shelters, household items, protective gear and maybe even satellites.

For over two decades, astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) have relied almost entirely on materials shipped from Earth for scientific research and daily life — an exception is water, which is recycled from wastewater on the station.

Thanks to the growing commercial space industry and a global interest in long-term missions beyond the ISS, which sits 250 miles (402 kilometers) above ground, scientists are developing methods to manufacture supplies off-Earth. The end results would help reduce flight costs during interplanetary travels to the moon, Mars and maybe beyond, advocates say.

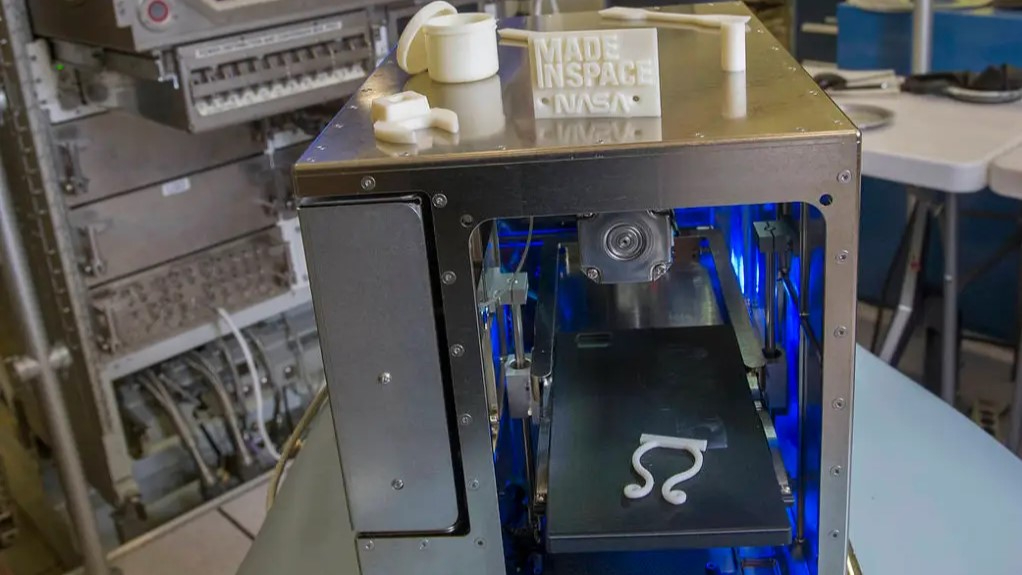

In a recent update on the topic, scientists are studying how 3D printing — a popular technique of building objects by wringing out chosen materials like molten plastic, glass or metal — works in microgravity. Because 3D printing relies on spitting the material of choice from a nozzle, layer by layer as it hardens into a desired pattern, gravity is an important aspect of the mechanism.

Related: Watch NASA test a 3D-printed rocket nozzle designed for deep space (video)

Scientists imagine the effort could help astronauts build various resources on-demand someday, from space station parts to nanosatellites, and even to full-scale satellites from mined asteroid material. Moreover, it might be possible to 3D print habitats on the moon and other planets down the line as well, ultimately minimizing the number of necessary cargo resupply missions.

"A spacecraft can't carry infinite resources, so you have to maintain and recycle what you have and 3D printing enables that," study lead author Jacob Cordonier of West Virginia University said in a statement. "You can print only what you need, reducing waste."

On Earth, a 3D printer can effortlessly design all sorts of things including camera lenses, guitars, cell phone cases and even full-scale implants and prosthetic body parts. In space, though, even slight movements can wreak havoc on intricate designs — and gravity dictates those movements. Yet how any type of object-building material behaves while squeezing out of a printer in space versus on Earth is not very well understood.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That's where the new study comes in. Cordonier and his team found titanium dioxide foam, the material used to build 3D objects in this case, oozed out differently in microgravity compared to Earth's gravity and recorded those variations. The researchers say this knowledge would be useful in pinning down how various parameters of the printer, like building speed and pressure, are likely to interact in microgravity.

Titanium was selected for several reasons. First off, it's lightweight and more resistant to corrosion as compared to stainless steel, meaning it's a cost-effective choice for 3D-building objects in space. And second, the moon itself has minerals like titanium, which means future lunar explorers might be able to mine their 3D printing material straight from the ground.

"We know the moon contains deposits of minerals very similar to the titanium dioxide used to make our foam," study co-author Konstantinos Sierros, a professor in the mechanical and aerospace department at West Virginia University, said in the statement. "So the idea is you don't have to transport equipment from here to space because we can mine those resources on the moon and print the equipment that's necessary for a mission."

Previous research has confirmed that regions on the moon are abundant in titanium ore, and few lunar rocks even sported 10 times more of the precious mineral than when compared to how much is contained in rocks on Earth. Lastely, the material is known to block out almost all ultraviolet (UV) light emanating from the sun, the new study shows.

On Earth, our planet's protective blanket of atmosphere occludes a significant amount of UV light. "In space or on the moon, there's nothing to mitigate it besides your spacesuit or whatever coating is on your spacecraft or habitat," said Cordonier.

So all kinds of astronaut equipment constructed using titanium dioxide could be an effective shield against UV light. But as if that wasn't enough, it also appears the mineral can use light to promote useful chemical reactions like purifying air, or even water.

The team has previously 3D printed on a parabolic flight completed with a Boeing 727, when the path's peak led to 20 seconds of weightlessness. Next, they envision sending the printer on 6-month trip to the ISS to monitor the printing process in detail.

This research is described in a paper published last month in the journal ACS Publications.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.