The Sentinel 6 satellite is now tracking Earth's rising sea levels with unprecedented accuracy

The new European-American ocean-monitoring satellite Sentinel 6 Michael Freilich has started delivering ultra-precise measurements of rising sea levels on Earth a six-month shakedown period.

As the globe's climate changes, Earth's oceans are warming and rising. To keep a watch on the waters, scientists have been relying for three decades on eyes in the sky: satellites that closely track how seas are behaving around the world. And the latest such satellite, Sentinel 6 Michael Freilich, has just begun to send back data.

The spacecraft, named after the late NASA climate scientist Michael Freilich, lifted off from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California last November. In time, Sentinel 6 will be able to give scientists more precise data about ocean surfaces than its predecessors, accurate to only a few centimeters. As a result, it'll allow meteorologists to better track weather patterns, such as nascent hurricanes and accurately monitor temperatures and rising sea levels.

For now, its mission has just begun. "It's a relief knowing that the satellite is working and that the data look good," said Josh Willis, a project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in a statement. "Several months from now, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich will take over for its predecessor, Jason-3, and this data release is the first step in that process."

Related: Seas will likely rise even faster than worst-case scenarios predicted by climate models

Sentinel-6 is the latest launch in a proud lineage of ocean-watching satellites that began in 1992 with TOPEX/Poseidon, which for the first time enabled scientists to observe processes in the oceans on a global scale with a regular frequency. The Jason series soon followed: three satellites that launched in 2001, 2008, and 2016, respectively. Jason 3, the last of these, is still hard at work measuring sea levels and helping weather forecasters.

Sentinel-6, part of the European Union's Earth observation program Copernicus, now trails Jason-3 by 30 seconds in their orbits at an altitude of 830 miles (1,336 kilometers). The two satellites scan 90% of the world's oceans at regular intervals. Scientists then compare data from the two satellites to ensure that Sentinel-6 is up to the task before it takes over from Jason-3 as the main sea level monitoring craft.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

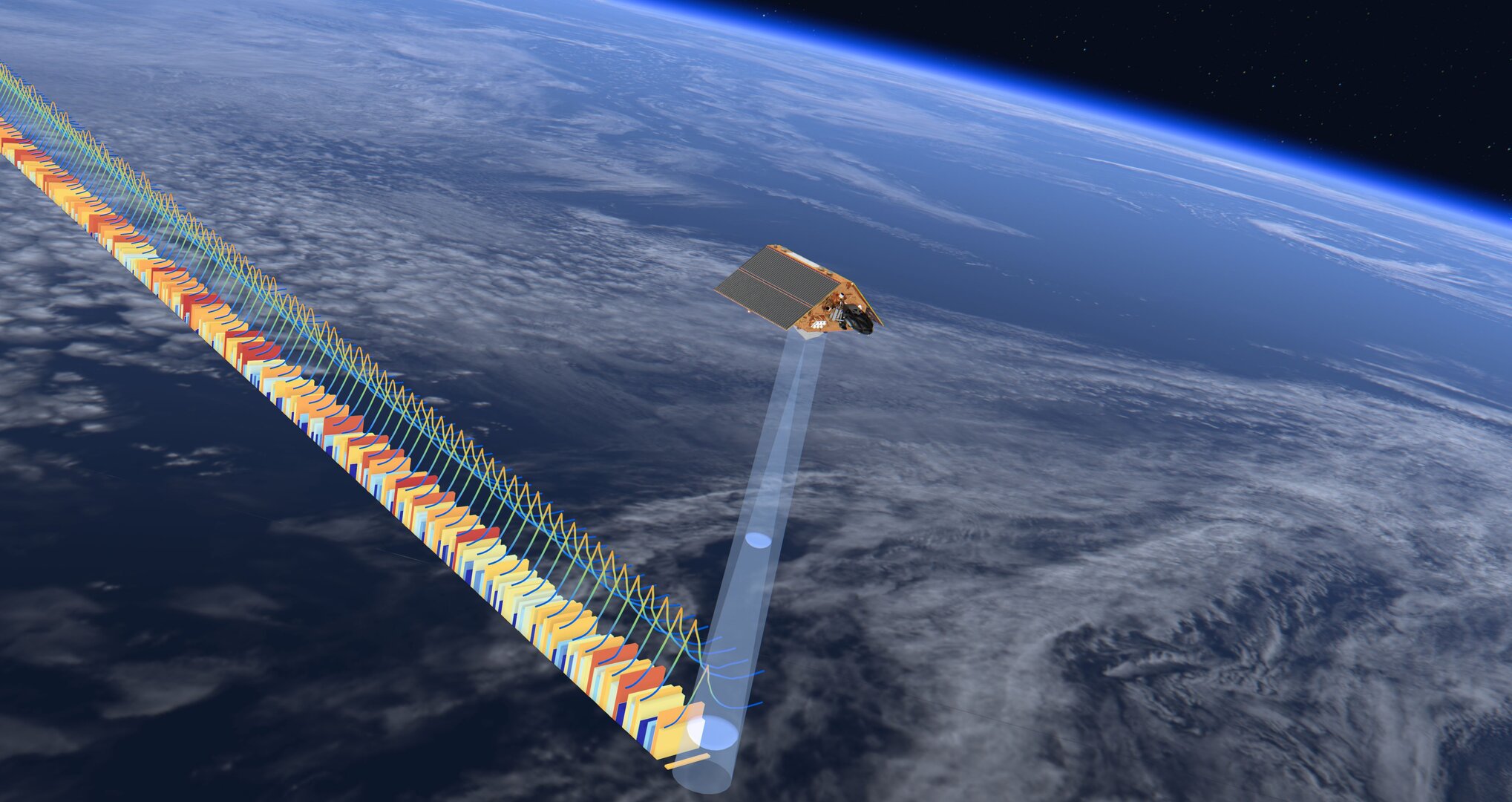

Sentinel-6’s main improvement over its predecessor is its advanced altimeter, called Poseidon-4. Based on synthetic aperture radar (SAR) technology, Poseidon-4 takes more precise measurements than conventional radar altimeters thanks to its ability to analyze the Doppler effect of the radar signal as it bounces off the sea surface and returns to the spacecraft. (Doppler effect is the shift in the frequency of the signal emitted by a moving source as it moves toward and away from the recipient.)

"To manage the transition from Jason-3's lower resolution measurements to Sentinel-6's high-resolution products with confidence, the Poseidon-4 altimeter acquires both conventional low-resolution measurements simultaneously with high-resolution synthetic aperture radar measurements," Craig Donlon, ESA's Sentinel-6 mission scientist, said in a European Space Agency statement. "We are really pleased to see that the data from Sentinel-6 show great performance based on validation by independent measurements on the ground."

Two streams of data from Sentinel 6 are now available to the global weather forecasting community, providing information about the sea surface height with accuracies of 2.3 inches (5.8 cm) and 1.4 inches (3.5 cm) respectively. The first data stream is available immediately upon acquisition. The second is released two days later after additional processing. Later this year, even more precise data sets, accurate to 1.2 inches (2.9 cm), will be released to climate researchers, NASA and ESA said in their statements.

In addition to NASA and ESA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and France's National Centre for Space Studies contributed to the mission. The spacecraft is operated by the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT) in Darmstadt, Germany.

Sentinel-6 won't be the last of its kind. A twin satellite, Sentinel-6B, is scheduled to launch in 2025. The two Sentinel-6 satellites will ensure that scientists will keep receiving the most accurate data about sea levels in the fourth decade of satellite measurements.

This data is especially important as climate change accelerates global sea level rise, a trend scientists have observed over the past three decades and worry is set to continue.

The ocean absorbs more than 90% of the heat trapped by the planet due to the increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, NASA said in the statement. As the water heats up, its volume expands, causing sea-level rise. As the planet warms, the melting ice sheets add further height. As a result, many low lying coastal areas all over the world already face frequent flooding with some potentially becoming uninhabitable in the future. The Sentinel-6 duo will help scientists better predict what awaits communities in the at-risk regions in the future.

"These initial data show that Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich is an amazing new tool that will help to improve marine and weather forecasts," said Eric Leuliette, program and project scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Maryland. "In a changing climate, it's a great achievement that these data are ready for release."

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.