NASA's OSIRIS-REx probe could make a 2nd stop at infamous asteroid Apophis

The space rock comes incredibly close to Earth in April 2029.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Hot on the heels of successfully snagging hunks of space rock in October, the scientists behind NASA's OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample-return mission are contemplating sending the spacecraft to study a second asteroid in 2029, this time the infamous Apophis.

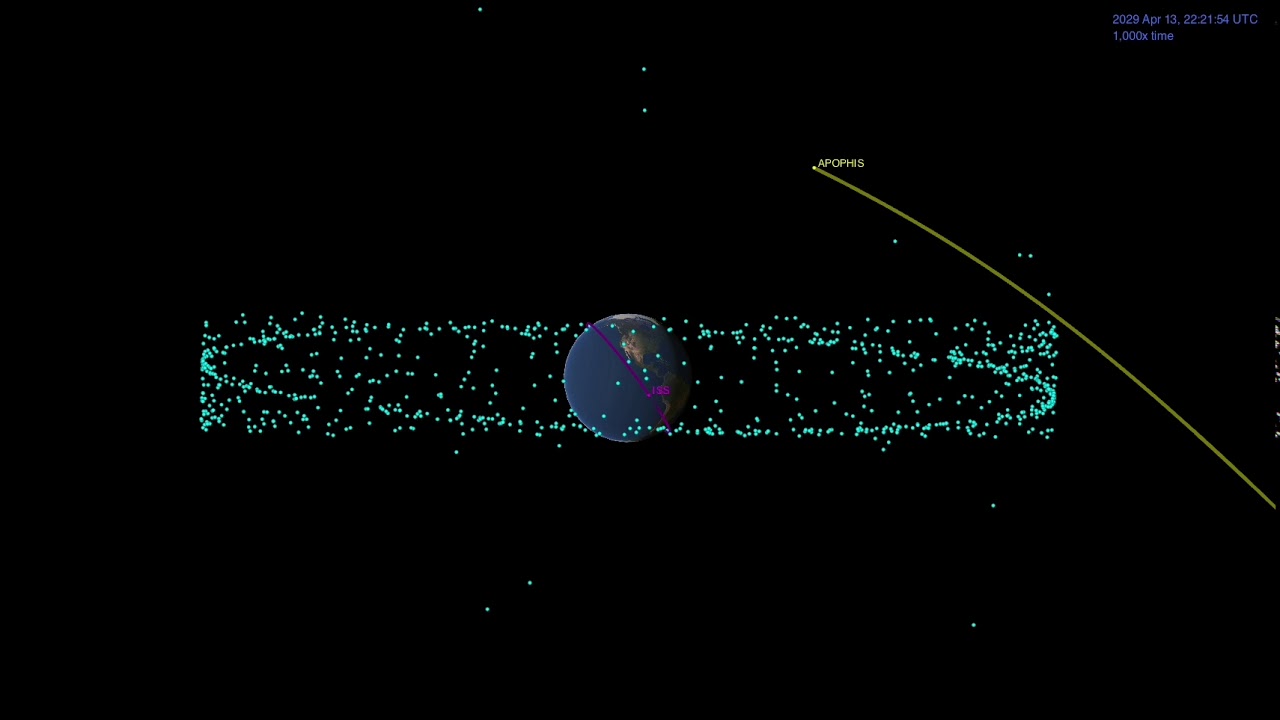

If that appointment comes to be, the spacecraft will arrive at Apophis in April 2029, just over a week after the asteroid makes a hair-raisingly close approach to Earth, within about 19,800 miles (31,900 kilometers) of our planet's surface. Scientists are confident that the asteroid won't impact Earth, but Apophis still has quite a reputation for a space rock, and discovering OSIRIS-REx could visit it provided an unexpected opportunity for the mission.

"Definitely it was a surprise, a very good surprise," Dante Lauretta, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona and the principal investigator for OSIRIS-REx, told Space.com of the moment in October 2019, when a team member reported that the spacecraft could make a long stay at Apophis.

Related: Huge asteroid Apophis flies by Earth on Friday the 13th in 2029 — a lucky day for scientists

"I thought for sure extended-mission targets were going to be flyby kind of opportunities, more traditional," Lauretta said. "Those are pretty easy to design in the inner solar system. But when [the OSIRIS-REx mission designer] came back and said we could put the spacecraft into orbit around a second large near-Earth asteroid, I was really excited."

But of course, the priority for the OSIRIS-REx team has been the primary mission of the spacecraft (formally dubbed the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer): collect and deliver a sample from the asteroid Bennu for scientists to analyze in their laboratories on Earth.

That task is going smoothly: OSIRIS-REx collected its space rock on Oct. 20 and will leave Bennu for the long journey home sometime this spring, arriving in September 2023. And just like the Japanese Hayabusa2 asteroid-sampling mission, which returned its samples from an asteroid called Ryugu in December, only a small capsule will actually return to Earth, jettisoned by the main spacecraft, which will then be free to explore other destinations — assuming, of course, the paperwork comes through.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The OSIRIS-REx team plans to propose an extended mission to NASA in the summer of 2022, Lauretta said. Visiting Apophis is one option for what that extended mission could look like, but so far, it's the only target that engineers have found the spacecraft could visit long-term. And a flyby might not do the spacecraft justice in terms of its capabilities and current condition, which Lauretta said is "excellent."

"We don't have a solution that gets us to rendezvous with another asteroid at all right now," Lauretta said. "It really is the unique nature of the Apophis close approach to the Earth in 2029 that even enables us to do this."

Same spacecraft, new asteroid, new science

OSIRIS-REx has lost only one mode of one instrument; otherwise, everything is in working order, Lauretta said.

In fact, a second asteroid visit would give scientists the opportunity to use an instrument that never actually studied Bennu: OSIRIS-REx was equipped with two lasers for the spacecraft to shoot off the rock and study the echo to facilitate its landing and sampling maneuver. But when the spacecraft arrived, mission personnel learned the asteroid was far too rocky for the system to work and devised an alternative navigation system.

Most lasers don't last long in space, so having two working lasers on a spacecraft older than a decade is rare, Lauretta said. "Having two fresh lasers that we've never used, I'm actually kind of excited about that," he said. "Especially because we built the hardware and we never got to use it. I just feel bad for the instrument. Like, aww, you got all the way to Bennu and all you got to do is get checked out and then we turned you off and you never got to see any action."

In general, an observation campaign at Apophis would likely look quite similar to what the spacecraft did at Bennu.

First, there's a long chain of approach observations, starting with the asteroid seen as just a speck of light, slowly growing into a whole new world. That sequence would begin perhaps around April 8, 2029. OSIRIS-REx won't have a front-row seat to Apophis' close approach, which will occur on April 13.

But seeing the aftermath of the encounter could more than make up for the late arrival, Lauretta said. Scientists expect the brush with Earth's gravity to affect Apophis itself — its precise location, spin and even the space rock's surface and interior structure. The spacecraft would be able to look for signs of what took place during the close approach. "We're really interested in the effect that passing deep into the Earth's gravity field has on the asteroid properties," Lauretta said.

Particularly prominent might be a change in how the asteroid spins. A second possibility the spacecraft could explore is that the close approach would sculpt the space rock's surface as Earth's gravity tugs at Apophis.

"It could trigger mass movement on the surface, and we would definitely be looking for that," Lauretta said. "Even though we might not see the motion due to the gravitational interaction with the Earth, we could see evidence that things had moved recently: freshly exposed surfaces, maybe even a population of particles that were kicked up, that are in orbit around Apophis."

But Lauretta isn't convinced that the drama of the asteroid's flyby is necessary to justify sending OSIRIS-REx on to Apophis once its precious cargo is delivered. Bennu and Apophis belong to different asteroid families with similar structures, and OSIRIS-REx was designed to create incredibly detailed portraits of large space rocks.

"In order to get as much science out of this vehicle as possible, it would be great to go to a different asteroid with a different composition, and collect the same kind of high-fidelity data that we had to generalize our understanding of the physical environment of asteroid surfaces as we've learned from the OSIRIS-REx mission," Lauretta said.

Sending OSIRIS-REx to visit a second asteroid could also help solve perhaps the biggest mystery the spacecraft discovered at Bennu: streams of particles shooting off the rock into space. "Those surprised us so much at Bennu," Lauretta said. "That's a day that I'll never forget, when I saw that first image of what looked like an eruption from the asteroid. And we don't know what's causing those."

The ejections could depend on Bennu's water-rich composition, or they might be a more common trait. As an asteroid of similar size and structure but very different stony material, Apophis could settle that question. "One of the hypotheses is that this is due to micrometeoroids impacting the asteroid," Lauretta said. "If that's the case, Apophis should have just as many particles as Bennu."

And then there's that ineffable quality that Apophis carries with it, from its discovery in 2004, when scientists' measurement of its orbit was uncertain enough that in some scenarios, its 2029 flyby went very, very badly indeed, with the asteroid slamming into Earth. Additional observations cleared up the concern, but it's a difficult reputation to shake for an asteroid named after a mythological Egyptian serpent of chaos.

"It really does enable some unique science," Lauretta said. "Quite honestly, any large asteroid that popped up as a rendezvous target would be super exciting for us. The fact that it was Apophis! Apophis is just famous, so everybody knows exactly what I'm saying when I tell them the asteroid that we want to target."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.