Huge Asteroid Apophis Flies By Earth on Friday the 13th in 2029. A Lucky Day for Scientists

COLLEGE PARK, Md. — The solar system has a sense of humor: A decade from now, on Friday, April 13, 2029, a large asteroid will streak across the sky — but it's a cause for excitement, not fear, scientists say.

That asteroid, called Apophis, stretches about 1,100 feet (340 meters) across and will pass within 19,000 miles (31,000 kilometers) of Earth's surface. That might sound scary, but scientists are positive that it will not hit Earth. Instead, it's a once-in-a-lifetime chance for scientists to truly understand asteroids near Earth.

"The excitement is that an object this large comes this close about once per thousand years, so it's all about, What's the opportunity?" Richard Binzel, a planetary scientist at MIT, said yesterday (April 30) during the International Academy of Aeronautics' Planetary Defense Conference, which is being held here this week. The asteroid's proximity and size will also add to the encounter's brightness, so Apophis will capture eyeballs — about 2 billion people should be able to see it pass by with their naked eyes, he said.

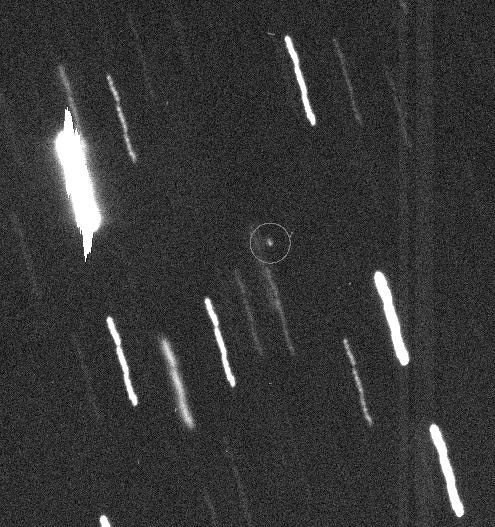

Related: Huge Asteroid Apophis Revealed in Photos

And of course, scientists have a full 10 years to plan before the space rock makes its closest approach. That means they have time to draw up a wish list of what they'd like to learn, sort out what can be tackled from Earth and dream up spacecraft designs that could give them a front-row seat to the flyby.

Although scientists are positive Apophis won't hit Earth in 2029, they can't yet rule out possible collisions many decades in the future, and there are plenty of other large space rocks orbiting the sun in Earth's neighborhood. Experts in planetary defense track these objects and prepare techniques that could divert any that do pose a threat. And data gathered about Apophis could inform what scientists know about these other asteroids, since this particular space rock seems superficially similar to about 80% of the potentially hazardous asteroids scientists have identified to date.

Related: Asteroid Apophis Gives a Earth Close Shave in 2029 (Infographic)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Asteroid scientists and planetary defense experts have already begun that work, with a series of presentations at the conference here highlighting topics they'd like to consider between now and the 2029 Apophis flyby.

Those proposed investigations bridge the two disciplines, asking questions applicable both to humanity's self-interest and to our greater understanding of the solar system we live in. Take, for example, the interior structure of Apophis, which would be a vital piece of information for engineers to understand if they want to try to break apart the space rock or push its collision course away from Earth. But that information would also likely offer clues to how Apophis formed.

"You could argue, is this science or planetary defense?" Binzel said. "But there is no argument, it's all one and the same."

A key topic of interest is the degree to which Earth's gravitational pull may distort Apophis during the 2029 close approach. Some scientists believe that previous flybys would have also stretched the space rock, and that other asteroids could be similarly affected during their own close approaches.

One question that asteroid scientists have that is also vital for planetary defense experts is the extent to which the sun's radiation nudges Apophis' orbit. That phenomenon, called the Yarkovsky effect, results from the temperature differential between the day and night sides of the asteroid.

Related: It's Time to Get Serious About Asteroid Threats, NASA Chief Says

The tweaks the Yarkovsky effect cause in an asteroid's orbit are so small that scientists struggle to distinguish the nudges from instrument hiccups. Although scientists have pinpointed Apophis' trajectory in 2029 to within a path just 7.4 miles (12 km) wide that stays thousands of miles away from Earth, they can't quite rule out possible impacts decades in the future — and that's in part because of uncertainty about the Yarkovsky effect.

In addition to flagging some key priorities for the next decade, scientists also discussed some top-level mission concepts that could lay the groundwork for spacecraft to visit Apophis before, during or after its close approach.

The successes of the past year or so have put engineers on a strong footing for such missions: NASA's Mars InSight mission placed the first robotically deployed seismometer on another planet. The first interplanetary cubesats flew with that spacecraft as the MarCO mission. And both NASA's OSIRIS-REx and Japan's Hayabusa2 have excelled at operating close to small asteroids.

Pieces of all those missions showed up in discussions about what scientists could send to Apophis. Several speakers discussed the possibilities offered by cubesat missions, including missions that paired twin spacecraft, as MarCO did.

Scientists also advanced the idea of putting a seismometer on the space rock — one design would impale Apophis like a harpoon — to pick up tiny vibrations through the space rock that could help scientists understand the interior structure of Apophis and how it's affected by Earth's gravity. Also among the ideas is a mission that would create an artificial crater on Apophis, as Hayabusa2 just did at an asteroid called Ryugu, in order to see below the weathered surface of the asteroid.

Some of those ideas may be too risky to be worthwhile, however, since scientists would need to be positive the manhandling wouldn't risk meddling in Apophis' current, safe trajectory. "We've got to be really careful, because this specific object will have intense public and even political pressure to avoid doing anything to change its orbit," James Bell, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University, said during his presentation. "That said, it's an opportunity for NASA and other space agencies, for it to be the PR event of the decade."

And that's the careful balance that asteroid scientists and planetary defense experts will need to achieve over the course of the next decade — making the most of the scientific and outreach opportunities Apophis' close flyby offers without causing panic, or still worse, accidentally creating a truly dangerous situation where there wasn't one before.

"The world will be watching," Binzel said. "It's up to us to get ready."

Editor's Note: This article was corrected to include James Bell's affiliation of Arizona State University.

- Humanity Will Slam a Spacecraft into an Asteroid in a Few Years to Help Save Us All

- Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space

- Wow! Asteroid Ryugu's Rubbly Surface Pops in Best-Ever Photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.