The Orionid meteor shower peaks this week, but don't expect to see many 'shooting stars'

Ask anyone to name a comet and there's a 90% certainty that the comet that is chosen will be Halley's. This most famous of comets, Halley's comet travels around the sun in an elliptical orbit that takes it beyond the orbit of Neptune and as close to the sun as inside the orbit of Venus; a trek that takes roughly 75 years to complete. Halley made its last visit to the sun in 1986 and it will return to the vicinity of the sun and Earth in midsummer of 2061.

I'd love to be around to greet Halley for a second time when it returns, but that's not likely to happen. You see, I was not quite 30 years old at its last appearance; I'll stick to my vitamins and do a lot of good wishing, but ... well, you do the math. It's possible, but not probable. And yet, during these next few mornings, both you and I will have a chance of sighting a few pieces of Halley — "comet litter" if you will — zipping through our atmosphere in the form of meteors.

The orbit of Halley's Comet closely approaches the Earth's orbit at two places. One point is in the early part of May, producing a meteor display known as the Eta Aquarids. The other point comes in the middle-to-latter part of October, producing the Orionid meteors.

A big handicap for viewing in 2021

The Orionid meteor shower is predicted to peak early on Thursday morning (Oct. 21). Under ideal conditions (a dark, moonless sky) about 20 of these very swift meteors can be seen per hour. The shower appears at about one-quarter peak strength for about two days before and after Oct. 21.

There is, however, a major drawback if you plan to watch for these meteors this year: a practically full moon. The full moon of October is traditionally known as the "Hunter's Moon" and in 2021 that will occur Wednesday (Oct. 20). Thereafter it will be waning (losing illumination) but it will still be virtually full when the Orionids are reaching their peak early tomorrow morning.

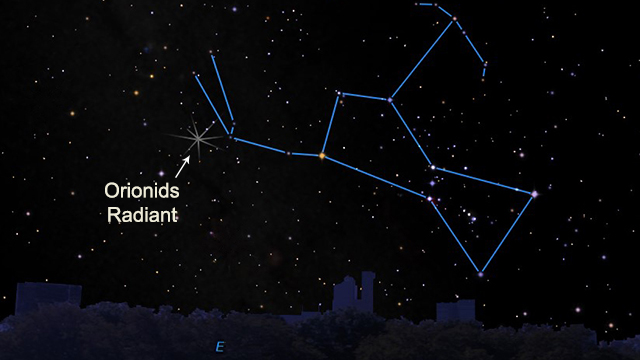

So, most of these streaks of light will likely be obliterated by the bright moonlight. Still, an exceptionally bright Orionid meteor, darting from out of the region of the constellation Orion (from where we get the name "Orionid") might still be glimpsed.

At 41 miles (66 kilometers) per second, they appear as fast streaks, faster by a hair than their spring sisters, the Eta Aquarids of May. And like the Eta Aquarid meteor shower, the brightest "shooting stars" tend to leave long-lasting trains.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And indeed, studies have shown that about half of all Orionids that are seen leave trails that lasted longer than other meteors of equivalent brightness.

Where and when to look

Currently, the Orion constellation (from which Orionid meteors appear to originate) appears ahead of us in our journey around the sun and has not completely risen above the eastern horizon until after 11:30 p.m. local daylight time. At its best during the predawn hours at around 5 a.m. — Orion will be highest in the sky toward the south. The Orionids are one of just a handful of known meteor showers that can be observed equally well from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Orionid activity tends to noticeably ramp up by around Oct. 17, when the first forerunners begin to appear. After peaking on the morning of Oct. 21, activity will begin to slowly descend, dropping back to only a few per hour around Oct. 25. The last stragglers can be sighted sometimes into the beginning of November.

Comet crumbs

If you do catch sight of one early these next few mornings, keep in mind that you'll likely be seeing the incandescent streak produced by material that originated from the nucleus of Halley's Comet. When these tiny bits of comet collide with Earth, friction with our atmosphere raises them to white heat and produces the effect popularly referred to as "shooting stars."

So it is, that the shooting stars that we have come to call the Orionids are really an encounter with the traces of a famous visitor from the depths of space and from the dawn of creation.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.