We need more rules for space junk and moon bases, NASA and US officials say

Departments working outside of Earth's atmosphere spoke to a group advising the VP Kamala Harris-chaired National Space Council on policy ideas.

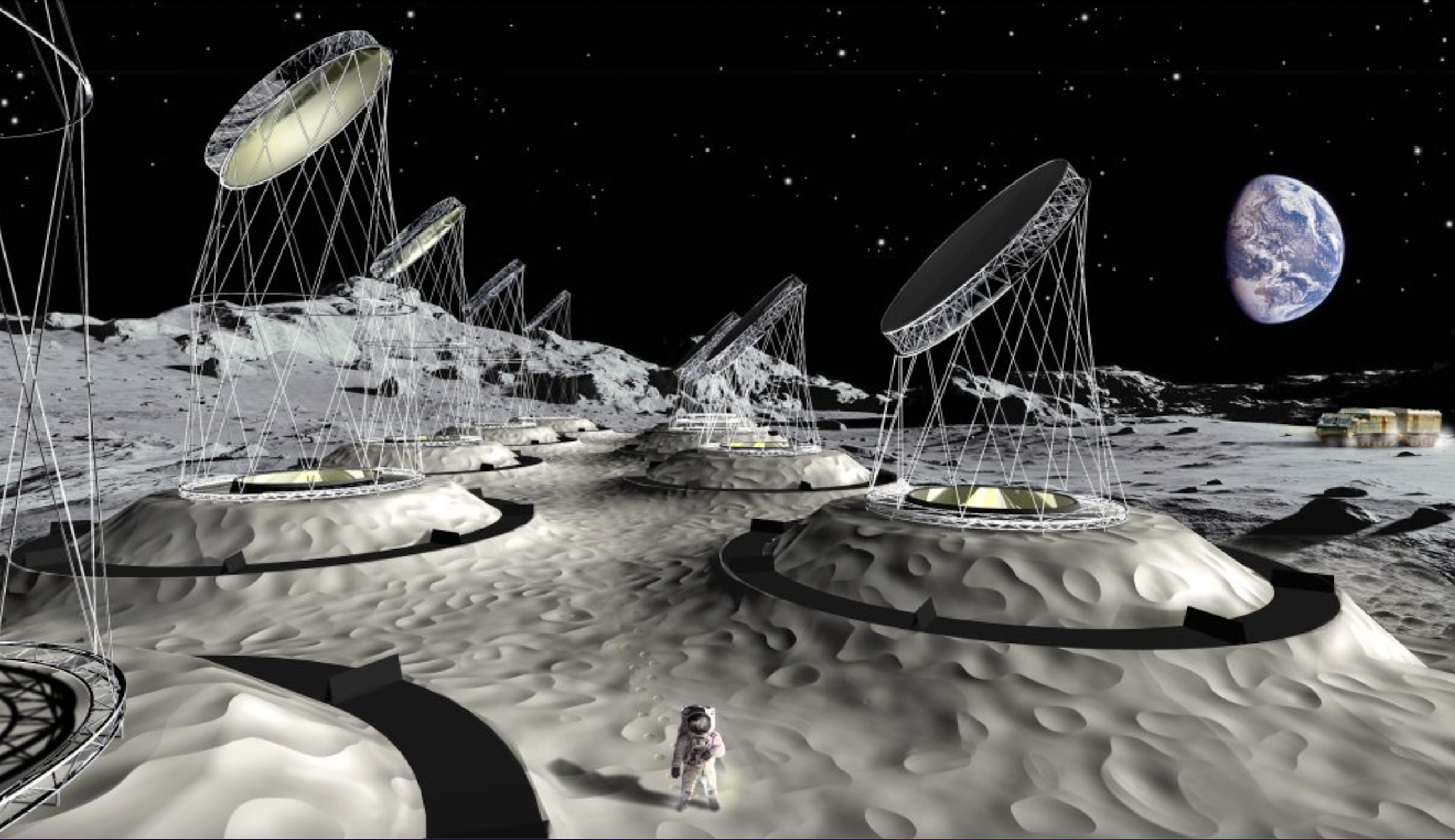

New space rules will need to come fast to support commercial space stations and moon settlements, and guard against swiftly-growing space debris.

That was a key takeaway message NASA and other government departments delivered to the National Space Council's (NSpC) users' advisory group, a set of representatives from industry, education and non-profit ventures that met Thursday (Feb. 23) in Washington, D.C.

Feedback from these meetings could eventually be used to form space policy for Earth and moon exploration and beyond, given that U.S. Vice-President Kamala Harris chairs the space council (and spoke with the users' advisory group later in the day about their progress.)

NASA deputy administrator Pam Melroy, speaking at the livestreamed meeting, urged the users' advisory group to consider recommending a fast refresh of space regulations to avoid "future barriers" to space exploration.

"We are not a regulator; that is not our role," Melroy said of NASA. Pointing to planned International Space Station commercial successors in the 2030s, she added: "We cannot be responsible for all activities on a commercial space station."

Exclusive: SpaceX, Amazon talk climate change with VP Kamala Harris

As NASA aims to put people and commercial payloads on the moon in 2025 with the Artemis program, and to open up the ISS to commercial astronauts and activities, more people and businesses have access to space than ever before. SpaceX and Axiom Space are among the beneficiaries, having flown ISS missions for astronauts themselves with NASA oversight. (SpaceX even flew a billionaire-funded independent excursion called Inspiration4.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That said, space law is an immensely complex business. Most spacefaring countries have signed on to the United Nations' Outer Space Treaty that governs international space activities. The treaty, however, was negotiated in the 1960s when government activities dominated the scene. More recently, several dozen members of the NASA-led Artemis Accords have also agreed to peaceful work in the 2020s and beyond, and to eventually establish new norms for lunar exploration.

Not everyone agrees on space rules, however. To take a few examples: China's practice of letting huge rockets fall to Earth uncontrolled has been condemned by the U.S. Joe Biden administration. Russia's decision to do anti-satellite test in orbit in 2021 created space debris that threatened not only the ISS, but SpaceX Starlink satellites that supply essential Internet service for remote populations on Earth.

SpaceX itself has come under criticism for creating bright satellites already interfering with astronomy and Indigenous observations, although they recently agreed to mitigations with the National Science Foundation. More generally, the space industry is increasingly facing calls to responsibly clean up space debris, launch less-polluting rockets and to create inclusive work environments for all backgrounds, genders and ethnicities.

Related: VP Kamala Harris calls to diversify US space workforce

I met with members of the National Space Council’s Users’ Advisory Group as we maximize the incredible opportunities of space. Together, with the space community, we’re working to address the climate crisis, create industries of the future, and explore our universe. pic.twitter.com/IHt955oI12February 24, 2023

Presentations to the NSpC users' advisory group, which included on Thursday big space companies like Blue Origin, Amazon, Boeing and Lockheed Martin, acknowledged that too much regulation can be stifling. (SpaceX is a member of the group, but was not in attendance on Thursday.)

Too little can also be harmful, however, creating confusion as to what proper space norms should be. As such, NASA and other government departments are urging the users' advisory group to make regulation recommendations to NSpC a priority.

"I think it's important to articulate publicly ... how space continues to be a source of American innovation and opportunity, as well as a source of leadership and of strength to our economy," said James Miller, the group's executive secretary and deputy director of NASA's policy and strategic communications, in the same meeting.

The U.S. is working to streamline its own space rules framework, for example through the Department of Commerce. While active in space since the 1980s in matters like remote sensing and space policies, the department is taking a more active role.

For example, the Trump administration's Space Policy Directive-3 will have Commerce eventually take over most of the space tracking system now managed by the Department of Defense.

"They have other responsibilities, but they'll still be deeply engaged," said Richard DalBello, director of the department's Office of Space Commerce, but noted considerable challenges remain. Getting countries like China to abide by the system, providing timely warnings about space debris and cleaning up space junk are among several concerns the department is managing.

DalBello noted that government departments like his have been impressed with NASA's approach to including commercial companies, such as programs that gradually handed off responsibility for ISS cargo and astronaut shipments to private industry: "Kudos to my government colleagues," he said.

But he warned that more help will be needed as the U.S. government, including civil and defense officials, moves out to the moon in stride with industry. Space mining and other new technologies will need more regulation. DalBello also suggested adding an element of "operator responsibility" into the current space law regime may encourage companies and countries alike to work together.

The users' advisory group will likely come together several more times before the 2024 federal election cycle. In a background briefing Wednesday (Feb. 23), a White House official told Space.com it's too early to predict what recommendations the group may make to the NSpC.

A published White House brief about the meeting yesterday, however, said the users' advisory group's mandate includes suggestions for "government policies, laws, regulations, treaties" as well as "practices across civil, commercial and national security space sectors", among other matters.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.