NASA works to maintain Russian cooperation in space while eyeing 'operational flexibility' for ISS

Operations are proceeding per usual despite Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

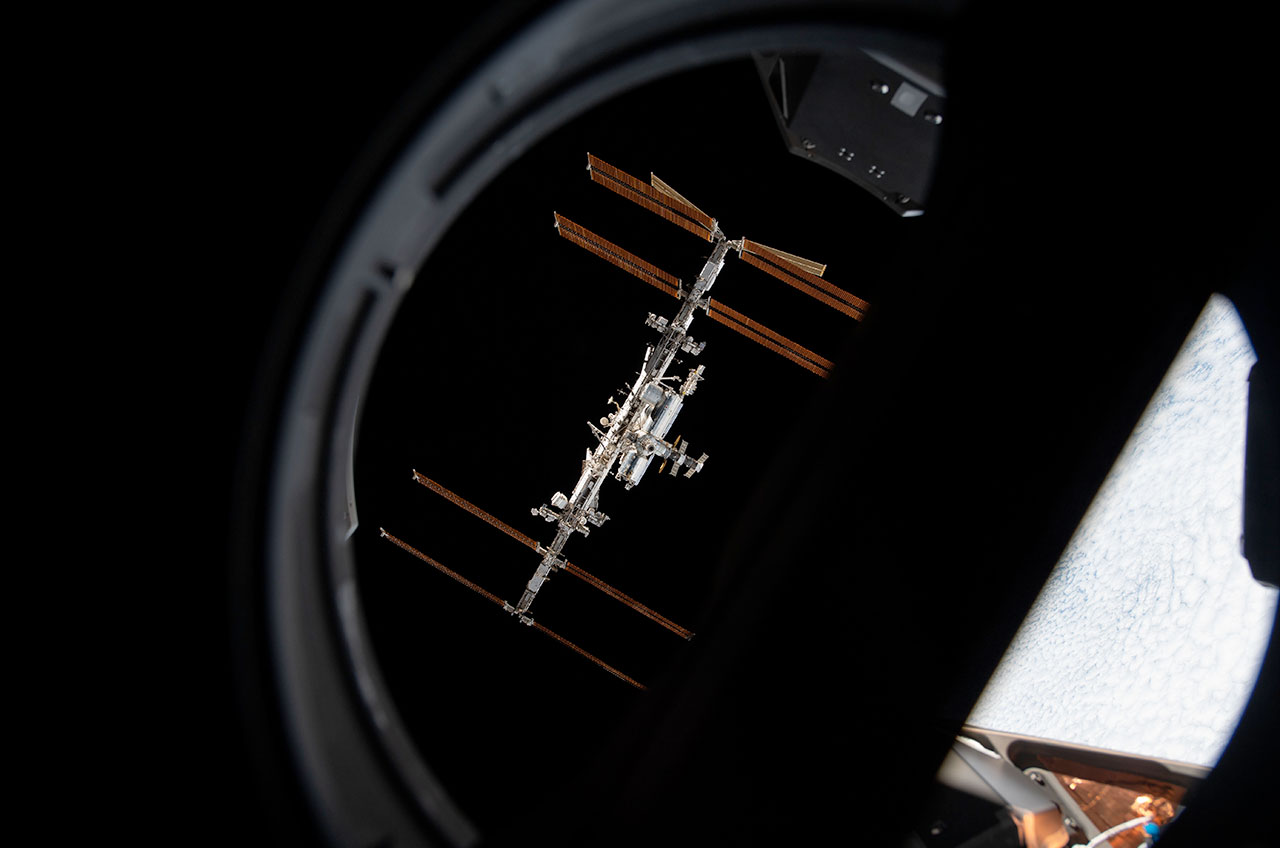

NASA is continuing to operate the International Space Station (ISS) as usual alongside Russia and the agency's other partners, but is weighing its options for the future amid Russia's ongoing invasion in Ukraine, the agency's top space operations official said Monday (Feb. 28).

"We understand this the global situation where it is, but as a joint team, these teams are operating together," NASA's associate administrator for space operations Kathy Lueders said of Russia's space agency Roscosmos in a call with reporters on Monday. "That said we always look for how do we get more operational flexibility [with] our cargo providers, and are looking at how do we add different capabilities."

Russia invaded Ukraine on Thursday in a series of military attacks, prompting numerous countries (including the United States) to impose economic sanctions. The space program has been affected directly through these sanctions, which U.S. President Joe Biden said would degrade Russia's space program.

Related: What the Ukraine invasion means for US-Russian partnership in space

Additionally, Russia has withdrawn services from several international coalition space projects, such as the European Arianespace Soyuz program that launched satellites from French Guiana. But on the ISS, Lueders said, so far the working environment is very similar to that from before the invasion.

"The one thing I want to make sure everyone on the call gets," Lueders said during the call, a briefing about private Axiom Space 1 mission to the ISS, "is we are not getting any indications at a working level that our counterparts are not committed to ongoing operation International Space Station."

Lueders reassurance came a few days after Roscosmos chief Dimitry Rogozin sent a series of fiery tweets accusing the United States of attempting to "destroy" the ISS partnership, and threatening to allow the space station to deorbit naturally in response.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Russia and the United States are tightly integrated principal partners on the multinational ISS, in a relationship that extends to shortly after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Russia is largely responsible for propulsive elements on the station, for example, while the United States side of the station supplies electrical power for the entire complex.

Additionally, Russia is responsible for periodically reboosting the space station through its Progress cargo spacecraft; in fact, an attached Progress did such a maneuver this past weekend despite Rogozin's comments. These orbital maneuvers are necessary to keep the relatively low-flying ISS (at 250 miles or 400 km in altitude) above the Earth's atmosphere; otherwise, the space station runs into tendrils of atmosphere in low Earth orbit and its orbit falls over time.

Lueders said NASA is, naturally, aware of the geopolitical situation and considering other options while still seeking a relationship with Russia.

There appear to be ready alternatives to keep the space station boosted, for example. Northrop Grumman's Cygnus spacecraft just arrived again at the space station last week for a cargo mission and the first operational reboost of that program.

Additionally, SpaceX founder Elon Musk has sent several tweets in recent days hinting that his company would be willing to step up to perform functions of Progress using the Dragon spacecraft, which already supplies cargo to the ISS.

It's not clear if these companies will be needed, however, and otherwise NASA is still prepared to rely on Russian Soyuz spacecraft to perform normal functions of spaceflight. Expedition 66 astronaut Mark Vande Hei, for example, is still slated to come back to Earth on a Soyuz spacecraft in April.

Vande Hei and his two Russian crewmates will, as usual, land in Kazakhstan; this procedure also requires NASA personnel (especially medical personnel) to travel to Russia, and then on to Kazakhstan, to support the landing. Lueders said during the press conference that this whole sequence should proceed as usual, despite numerous countries closing their airspace to Russian aircraft.

NASA's ability to launch astronauts to the ISS today is a bit different than in 2014, when Russia invaded the Crimean region of Ukraine and faced a different set of international sanctions. Back then, NASA was in between launching systems that could leave from the United States; the space shuttle had retired in 2011, and new commercial crew providers were still developing their spacecraft.

NASA was then relying upon Soyuz spacecraft from Kazakhstan to launch its astronauts, so when Rogozin was facing sanctions back then, he remarked on Twitter that the Americans should be prepared to launch their astronauts by trampoline. (As it turned out, however, Soyuz launches continued with no disruption.)

This time around, NASA does have an autonomous launch capability through SpaceX's Crew Dragon, which began operations in 2020. That said, the other commercial crew provider (Boeing) has seen its astronaut taxi role with Starliner delayed by years since a flawed uncrewed test mission in 2019.

After facing numerous technical, logistical and pandemic-related issues, an uncrewed launch of Starliner is set to finally take place again this year, ironically upon an Atlas V rocket that depends on Russian-made engines. United Launch Alliance, however, says it has enough engines on hand to support that launch ahead of a long-expected transition to its Vulcan rocket.

Starliner, however, will likely not support operational crews for many months, perhaps 2023 or so, assuming all goes well. If NASA astronauts lose access to the Soyuz, this means the Americans will only have one spacecraft available to fly crews until Starliner is ready.

In the longer term, there are questions concerning the persistence of the ISS beyond its multinational agreement expiry date in 2024. NASA has committed to flying the complex beyond 2030, and is funding several private space stations to replace some of the functions (such as research) by the late 2020s or so. Russia, however, would likely need to commit to continuing, along with international partners in Canada, Japan and several European nations.

Should the United States and Russia sever relationships in 2024 or earlier, publication Ars Technica pointed to a couple of options that could allow for it to keep flying. The Russian and American sides, for example, could permanently close the connecting hatch in Node 1 and resupply each other separately, almost like two separate space stations.

Alternatively, American vehicles could fully take over the reboost and propulsive elements, Ars Technica said, although that would be assuming this was possible in the absence of ground support from Roscosmos from Moscow.

Lueders said it would be "very difficult" to keep operating the ISS in a circumstance other than the existing international partnership that has "joint dependencies", which she said "makes it such an amazing program [because] it's a place where we live and operate in space in a peaceful manner."

Should the partnership disintegrate, she added, "it would be a sad day for international operations, that we can't continue to easily operate in space."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.