NASA's Mars sample return mission is in trouble. Could a single SLS megarocket be the answer?

NASA could get Mars samples back to Earth with a single launch of the Space Launch System rocket, Boeing says.

Boeing has put forward its own idea to help NASA get its Mars Sample Return project back on track and on budget.

NASA issued a solicitation for new ideas to get scientifically invaluable Martian material to Earth after being told the current plan is too expensive (about $11 billion), while also being too complex and facing scheduling issues.

Former NASA Chief Scientist Jim Green presented Boeing's vision for a rejiggered Mars sample return mission concept at the annual Humans to Mars Summit last week.

Related: NASA's Mars Sample Return in jeopardy after US Senate questions budget

The concept centers on using NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, for which Boeing is a lead contractor. The giant rocket, which performed well during its first, and so far only, flight — the Artemis 1 moon mission in late 2022 — could carry all the hardware needed to pull off an ambitious, multi-spacecraft Mars sample return mission, according to Green.

"So, to reduce mission complexity — one of the top things NASA wants to do — this new concept is doing one launch," he said in his presentation.

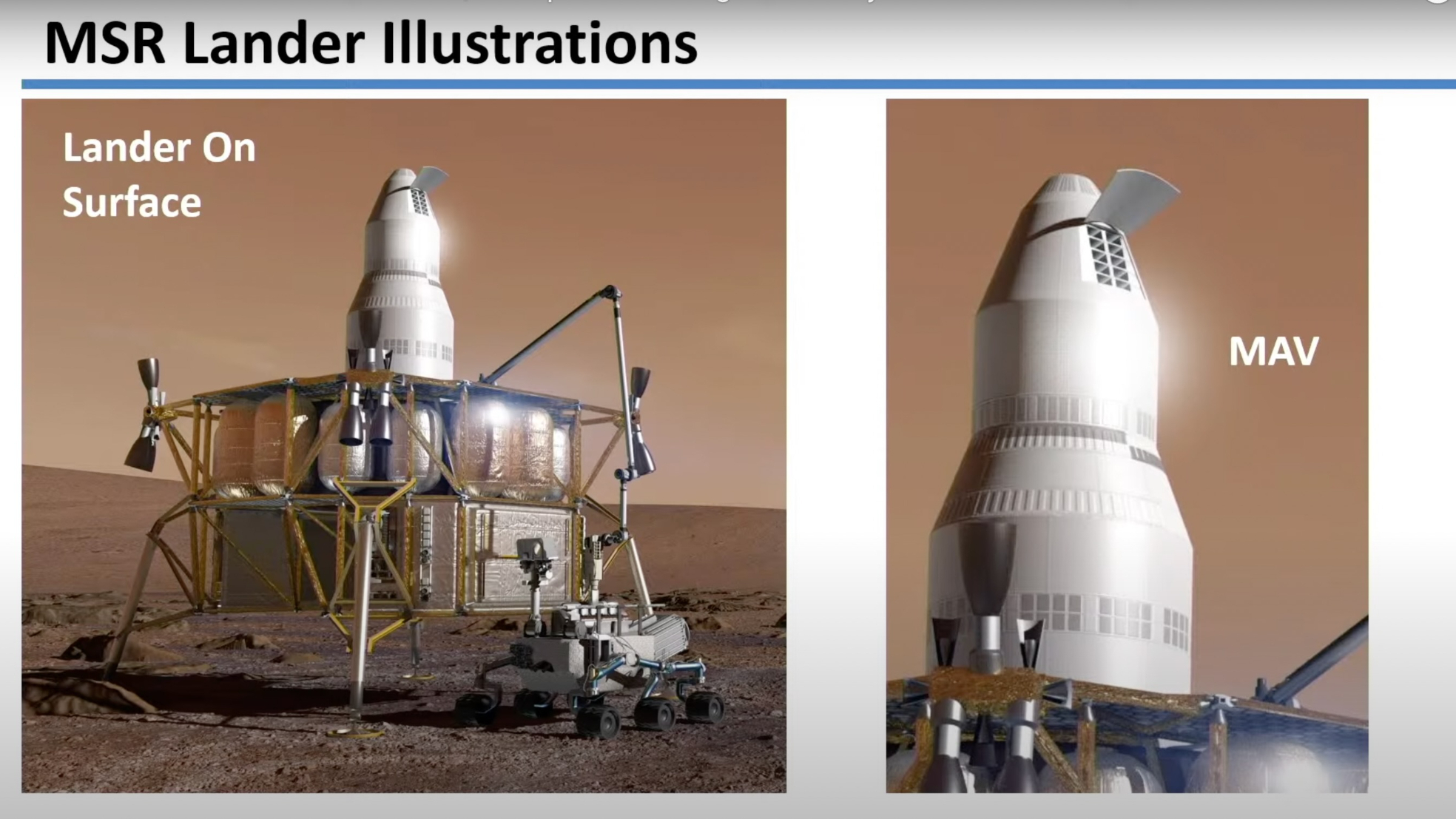

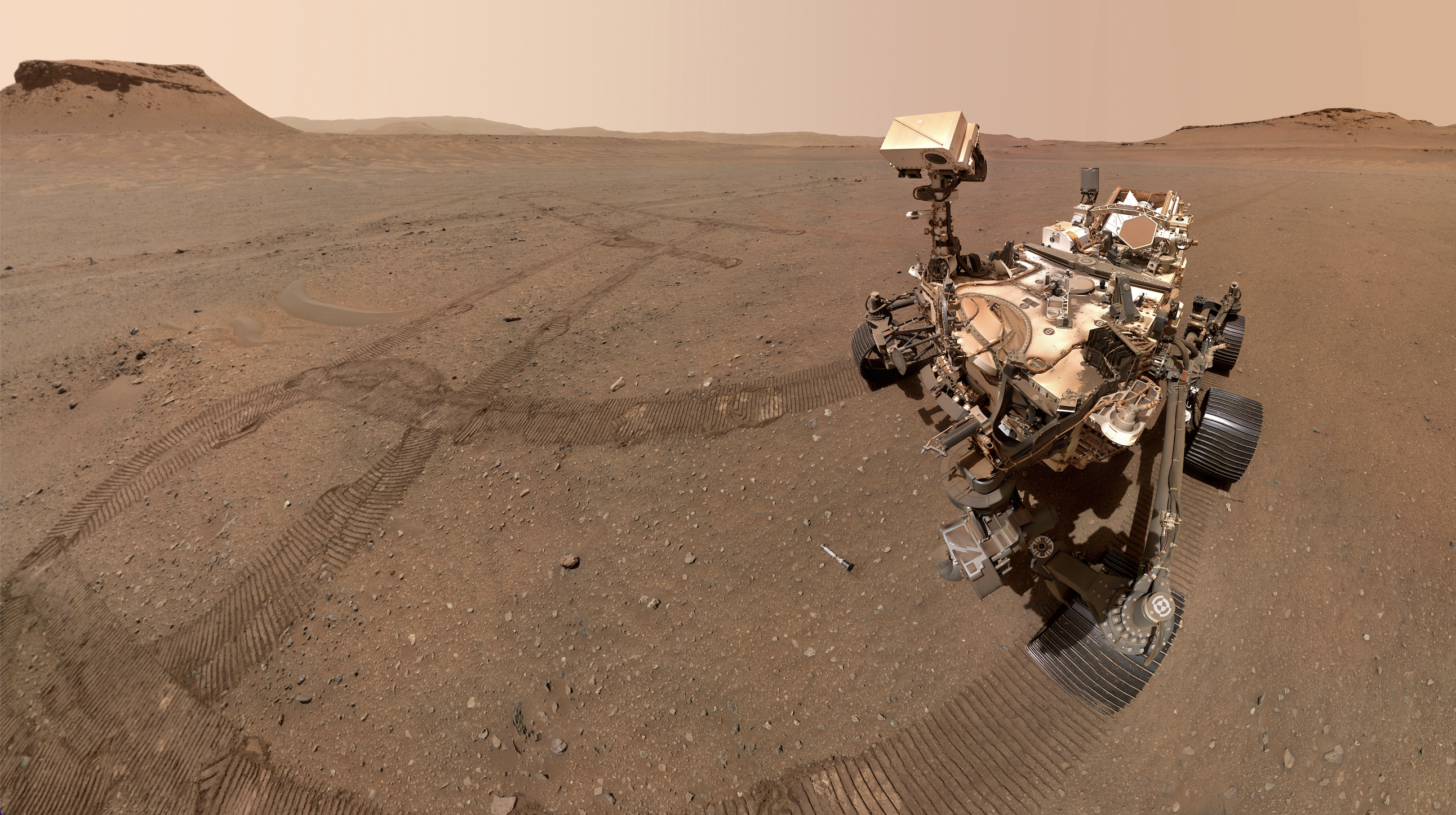

NASA's previous plan envisioned multiple launches to place a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) on the Martian surface, grab samples collected by the agency's Perseverance rover and return them to Earth. Boeing's single-shot concept would put a lander on Mars, with the help of an entry and descent aeroshell and a descent module with retro rockets, that could do all the work needed to get the precious samples home.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Boeing's proposed plan includes a fetch rover to retrieve Perseverance's samples. A two-stage MAV with a sample canister and an encapsulation system would be able to reach Mars orbit and then fire its engines to head home, instead of performing a Mars orbit rendezvous and docking with a transfer vehicle as in the original concept.

Ars Technica noted that, while attempting to cut costs, the use of the giant SLS would itself be expensive; a single launch would likely cost $2 billion at least. Contrary to Boeing's larger-MAV approach, NASA's initial re-thinking seemed to lean toward a smaller and cheaper MAV, and perhaps collecting fewer than the initially planned 43 sealed titanium tubes containing samples collected by Perseverance.

NASA is accepting proposals through May 17 and will begin charting a new path forward on MSR later in the year.

The MSR project remains a high priority for NASA, agency administrator Bill Nelson said last month when announcing the project revamp.

Green noted that returning samples before potential human missions is crucial for understanding the Martian environment, including soil toxicity and resource availability.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.