Celebrate 400 years of moon maps for Apollo 11's anniversary (gallery)

Telescopes, ship navigation and eclipses spurred the first detailed charts of Earth's nearest neighbor.

- Galileo: Shades of dark and light

- John Seller: Cartographer of water and space

- Johannes Hevelius: Maps and eclipses

- Giovanni Battista Riccioli: Naming the Sea of Tranquility

- Johann Tobias Mayer: Lunar eclipses

- Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt: A comprehensive moon atlas

- Maurice (Moritz) Loewy and Pierre Puiseux: Early moon photography

- U.S. Geological Survey: A Space Age view of the moon

- Ranger: Crash-landing spacecraft to map the moon

- Lunar Orbiter: Global maps of the moon

- Apollo 17: The last human landing

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

We've been mapping the moon in detail ever since telescopes were invented.

Humans last walked on the moon during the Apollo program, between 1969 and 1972. (And the 54th anniversary of the epic Apollo 11 landing is July 20.) NASA plans to return people to the lunar surface during the Artemis program as soon as 2025 or 2026. Getting spacecraft and people safely to the moon, however, requires high-definition imagery.

The U.S. Library of Congress gave Space.com permission to publish photos of a few of the moon maps in its possession, some of which are 400 years old. Below you can see sketches from people like Galileo, early moon photographs and pioneering spacecraft images.

Our personal histories influence how we discuss the moon. The Library of Congress is one of many U.S. museums with holdings from different cultures and genders, showcasing the diversity of viewpoints about our lunar neighbor.

At other institutions, you can view Native American interpretations of the moon at the National Museum of the American Indian. The Smithsonian Institution also has many lunar images of different cultures and genders, such as this stunning solar system quilt created in 1876 by American astronomer Ellen Harding Baker. International moon maps are also available at the University of Cambridge in England.

Related: 20 trailblazing women in astronomy and astrophysics

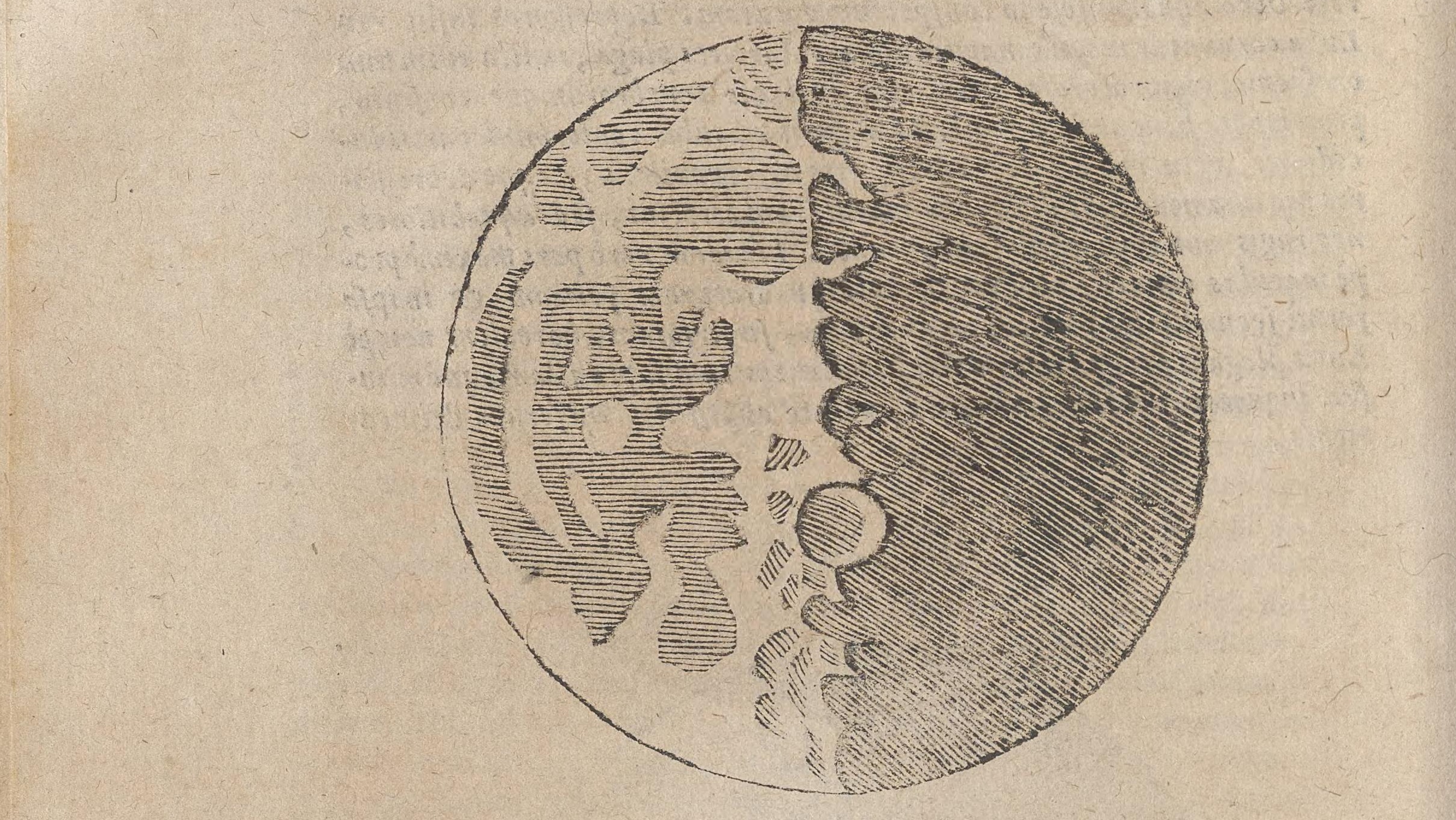

Galileo: Shades of dark and light

Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) is famous for his investigations that influenced Newton's laws of motion, as well as for using and improving early telescopes. He challenged the community's view of space in that era, including that celestial objects were perfect (craters on the moon showed him otherwise) and that Earth was at the center of the universe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Shown here is one of Galileo's first sketches of the moon, done around 1609 when such telescopic work was in its infancy. Galileo emphasized the contrast between light and dark using an artistic technique known as chiaroscuro, popularized by artists such as Caravaggio and Goya.

John Seller: Cartographer of water and space

John Seller (1632-1697) was an English mapmaker focusing on nautical navigation who was employed by kings Charles II, James II and William III. His work includes books such as "Practical Navigation" (1669), "Atlas Maritmus" (1669) and "An Epitome of the Art of Navigation" (1681), among others. The picture here (from 1700) is from one of his lunar atlases, which he began publishing in 1680.

"While his maps often lack beauty and finesse, Seller contributed significantly to English cartography by helping to establish the market for English-language maps and charts and encouraging the growth of the cartographic industry in 17th-century England," an archived webpage from the New York Public Library states.

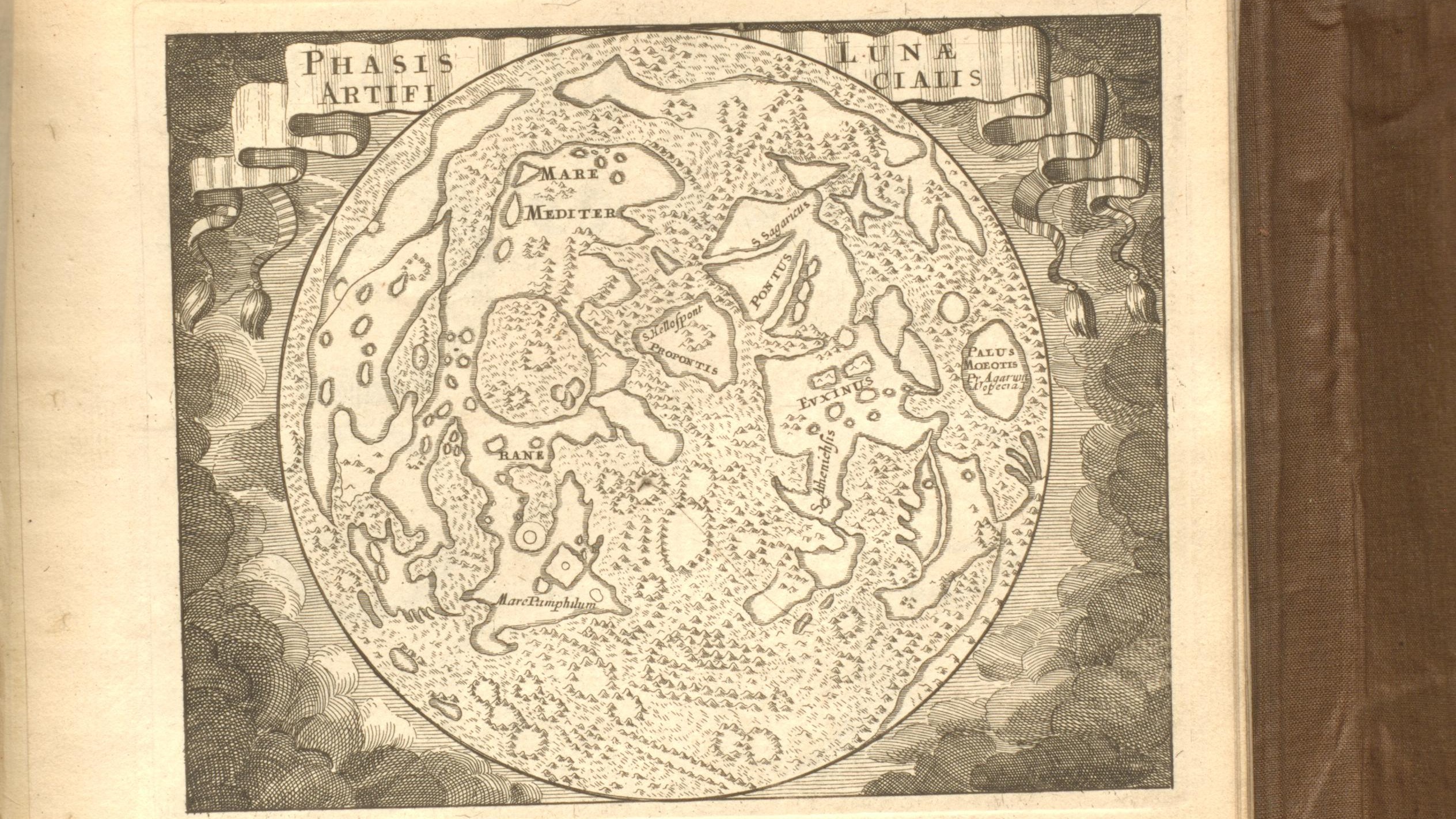

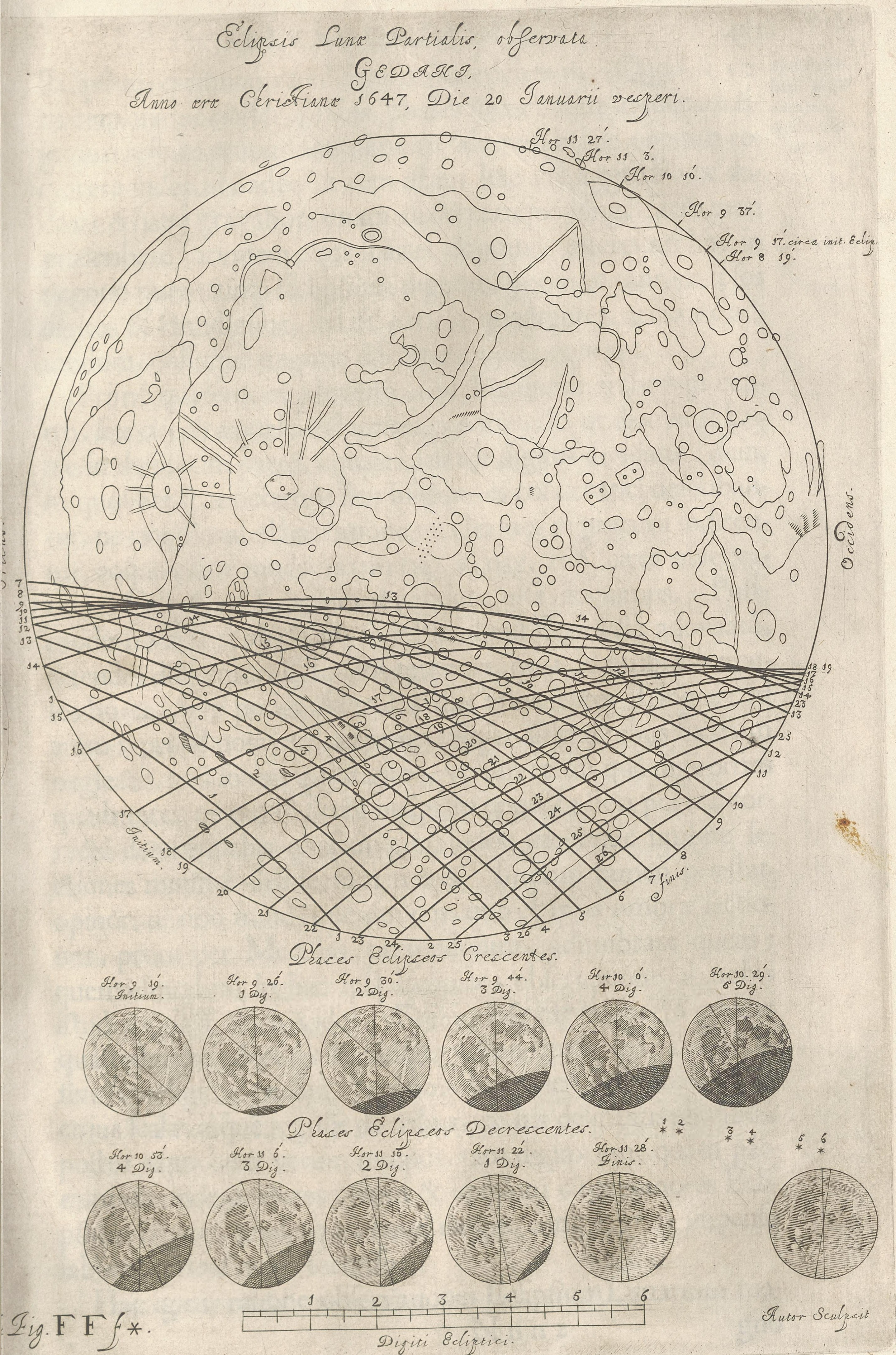

Johannes Hevelius: Maps and eclipses

Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), a Polish astronomer, made one of the first detailed atlases of the moon in 1647. The book, called "The Selenographia," includes some names for lunar mountains that are still in use, according to Britannica. He also compiled a catalog of 1,564 stars, which was the largest of its era.

Hevelius' lunar observations were helpful for navigation, particularly the search for an accurate way of measuring longitude at sea, according to Smithsonian Magazine. His detailed maps helped sailors in different locations estimate their position compared to a ground observatory, by comparing what they saw at a particular moment of time as the shadow crossed a part of the moon.

Giovanni Battista Riccioli: Naming the Sea of Tranquility

The Sea of Tranquility, where the Apollo 11 astronauts landed in 1969, was first named by Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598-1671). You can see here a moon map co-created by Riccioli and Francesco Grimaldi (1618-1663) on the right; the map on the left comes from Johannes Hevelius.

Riccioli's most famous work was "Almagestum novum" (The New Almagest), according to Oxford Reference, and it was not only for his moon mapping. Riccioli, a Jesuit priest, also presented 77 arguments against Nicolaus Copernicus, who was arguing (correctly, of course) that the sun sits at the center of our solar system.

It took a few decades for Copernicus' findings (themselves based on an ancient Greek astronomer known as Aristarchus of Somos) to be widely accepted in the astronomy community, especially since the powerful Catholic Church interpreted certain passages of the Bible to say Earth is at the center of the solar system.

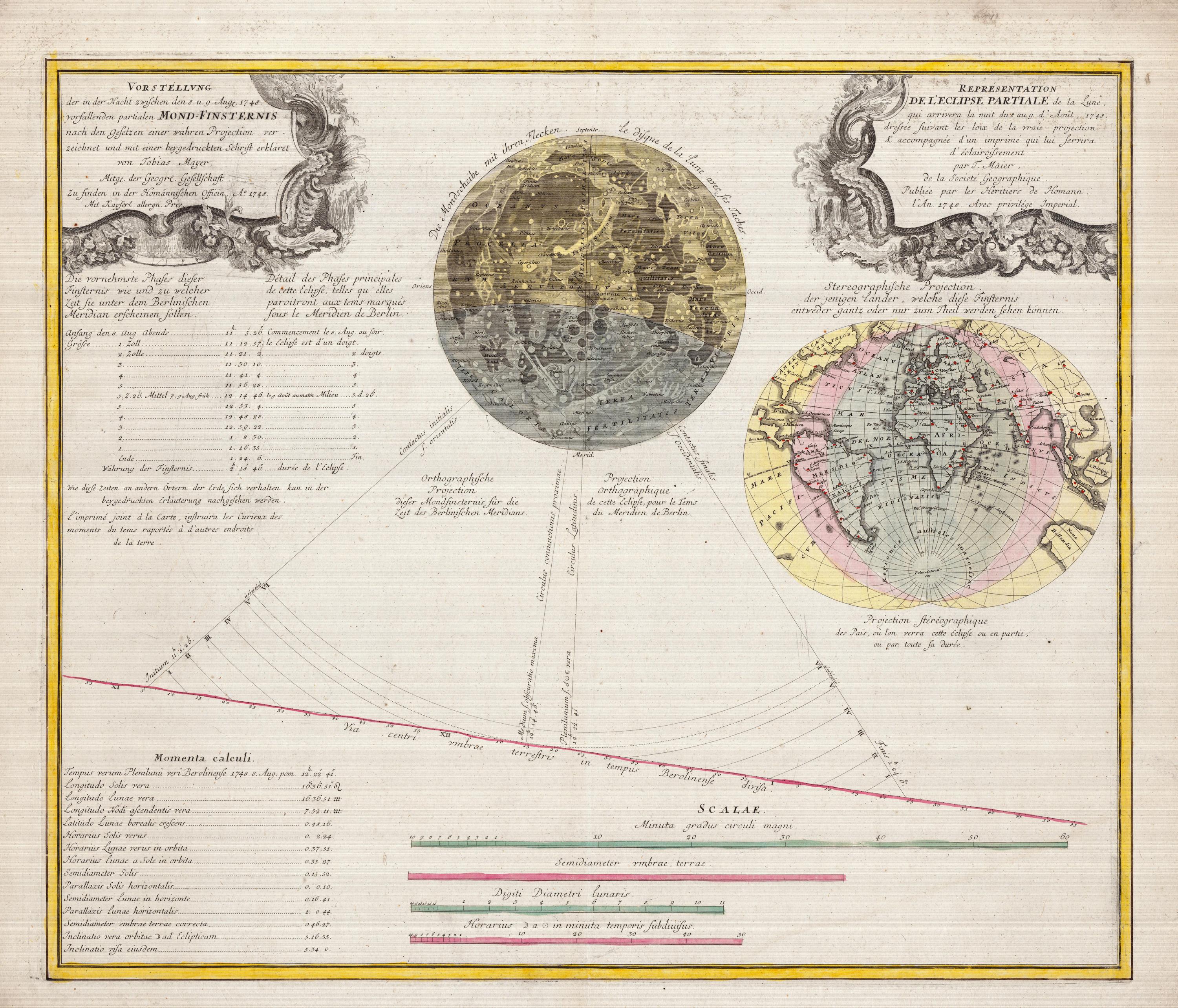

Johann Tobias Mayer: Lunar eclipses

German physicist Johann Tobias Mayer (1723-1762) is another lunar cartographer famous for developing maps to help sailors with navigating and with finding longitude at sea. Mayer is most famous for finding the libration (wobbling) of the moon as it orbits the Earth, according to Britannica.

The map you see here is from a lunar eclipse on August 8, 1748. It includes information in French and German showing technical data about the eclipse.

Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt: A comprehensive moon atlas

Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt (1825-1884) was a German astronomer and geophysicist who enjoyed studying the moon for his entire life, according to the Library of Congress. He was director of the National Observatory of Athens starting in 1858 and is famous for publishing an atlas of the moon based on maps of Wilhelm Lohrmann (1796-1840), one of whose examples is included here.

Lorhmann, the library wrote, "created a topographical series of the moon complete in 25 sheets. Schmidt edited and published all 25 sections of Lohrmann's lunar topography in 1878."

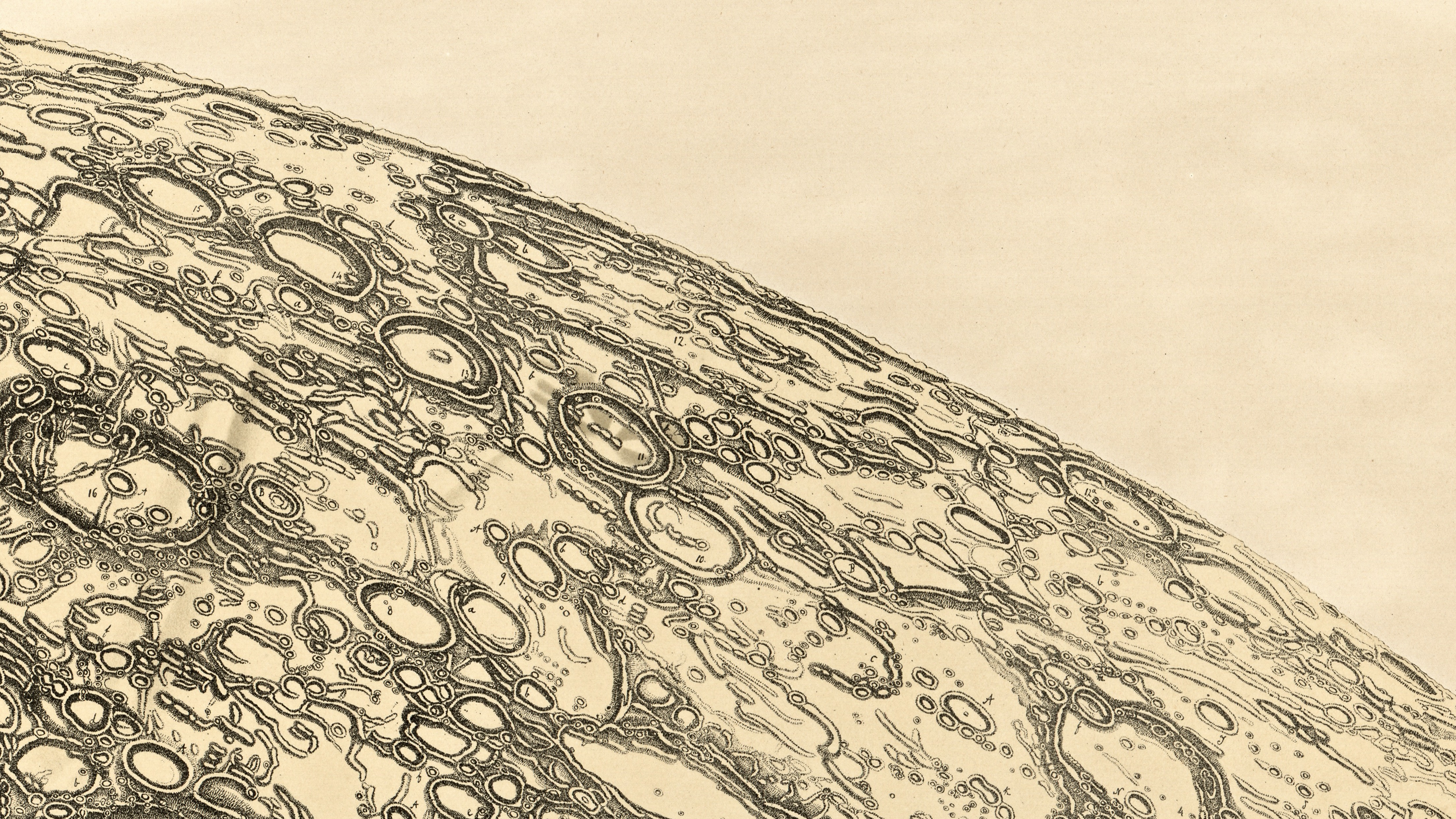

Maurice (Moritz) Loewy and Pierre Puiseux: Early moon photography

Maurice (Moritz) Loewy (1833-1907), an Austrian, received a position at the Paris Observatory in 1860 and then got French citizenship. He became director of the observatory in 1896, the same year he published an atlas of early moon pictures.

The book, co-created with French astronomer Pierre Puiseux (1855-1928), used a camera attached to a telescope. "A preset clock system was used to synchronize the camera and telescope with the lunar path," the Library of Congress stated. "The photographs were enlarged and transferred to an etching plate. Thousands of photographic prints were made from a single plate."

U.S. Geological Survey: A Space Age view of the moon

The first artificial satellite, the Soviet Union's Sputnik, reached Earth orbit in 1957. Soon after came both Soviet and U.S. missions to the moon to perform mapping, along with telescopic images using the best ground observatories available. The Military Geology Branch of the U.S. Geological Survey created a series of charts in July 1960 representing one of the best moon maps of the era.

Participating observatories in the effort included the McDonald Observatory (Texas), the Yerkes Observatory (Wisconsin), the Lick Observatory (California), and the Paris Observatory in France, according to the Library of Congress.

Ranger: Crash-landing spacecraft to map the moon

NASA's Ranger spacecraft series were also early moon explorers. The first clutch of them failed for various reasons as space engineering was in its infancy, but Rangers 7 through 9 all met their missions: to crash-land on the moon while taking pictures. The suicide dives were essential for early moon photography.

Sue Finley, an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, led the team of women who calculated the trajectories to send the Ranger spacecraft to the moon, according to PBS. They also played key roles in a set of landing spacecraft, called Surveyor, and designed the radio antennas that formed the Deep Space Network that still communicate with spacecraft around the solar system.

Black women engineers (later known as "Hidden Figures," since their work was not much talked about for decades) worked on numerous spacecraft trajectories of the early space program as well. Mathematician Katherine Johnson, for example, created calculations allowing the two spacecraft of Apollo (the command module and lunar module) to meet up with each other in lunar orbit. NASA's headquarters is now named after Johnson.

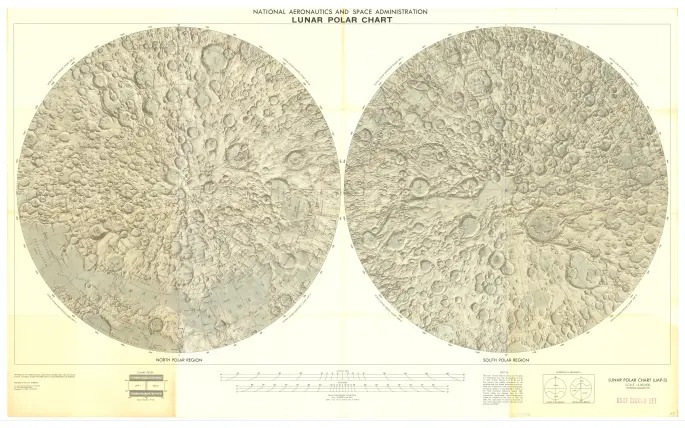

Lunar Orbiter: Global maps of the moon

Another keystone effort of early moon missions was the NASA Lunar Orbiter spacecraft series, which sent five missions successfully there in 1966 and 1967 to try to map the entire surface of the moon. They accomplished that goal almost entirely, mapping 99% of the surface and providing high-resolution maps useful for both crewed and uncrewed landings.

The chart shown here includes the moon's polar regions, based on photographs from each of the missions. The poles are not fully visible from Earth and represent how important spacecraft are to mapping other worlds, as well as our own.

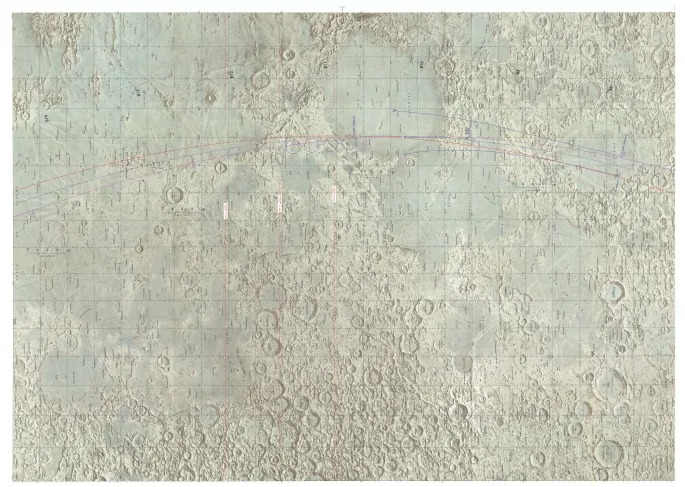

Apollo 17: The last human landing

While Apollo 17 is most famous for landing the last two people on the moon (so far) in 1972, it is also a representative mission of how humans have mapped the moon based on their own observations from up close. The map here is based upon photography taken in orbit and managed by Ron Evans, the command module pilot who did mapping and similar work while his two Apollo 17 colleagues were on the lunar surface.

The next mission to the moon, Artemis 2, includes three NASA astronauts and a Canadian astronaut. The four astronauts, led by NASA's Reid Wiseman, will launch on their round-the-moon mission no earlier than November 2024. The group includes the first of several types of folks to leave low Earth orbit: a woman (Christina Koch), a person of color (Victor Glover) and a non-American (Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen.)

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.