Space Travel Causes Joint Problems in Mice. But, What About Humans?

Can "zero-g" cause arthritis?

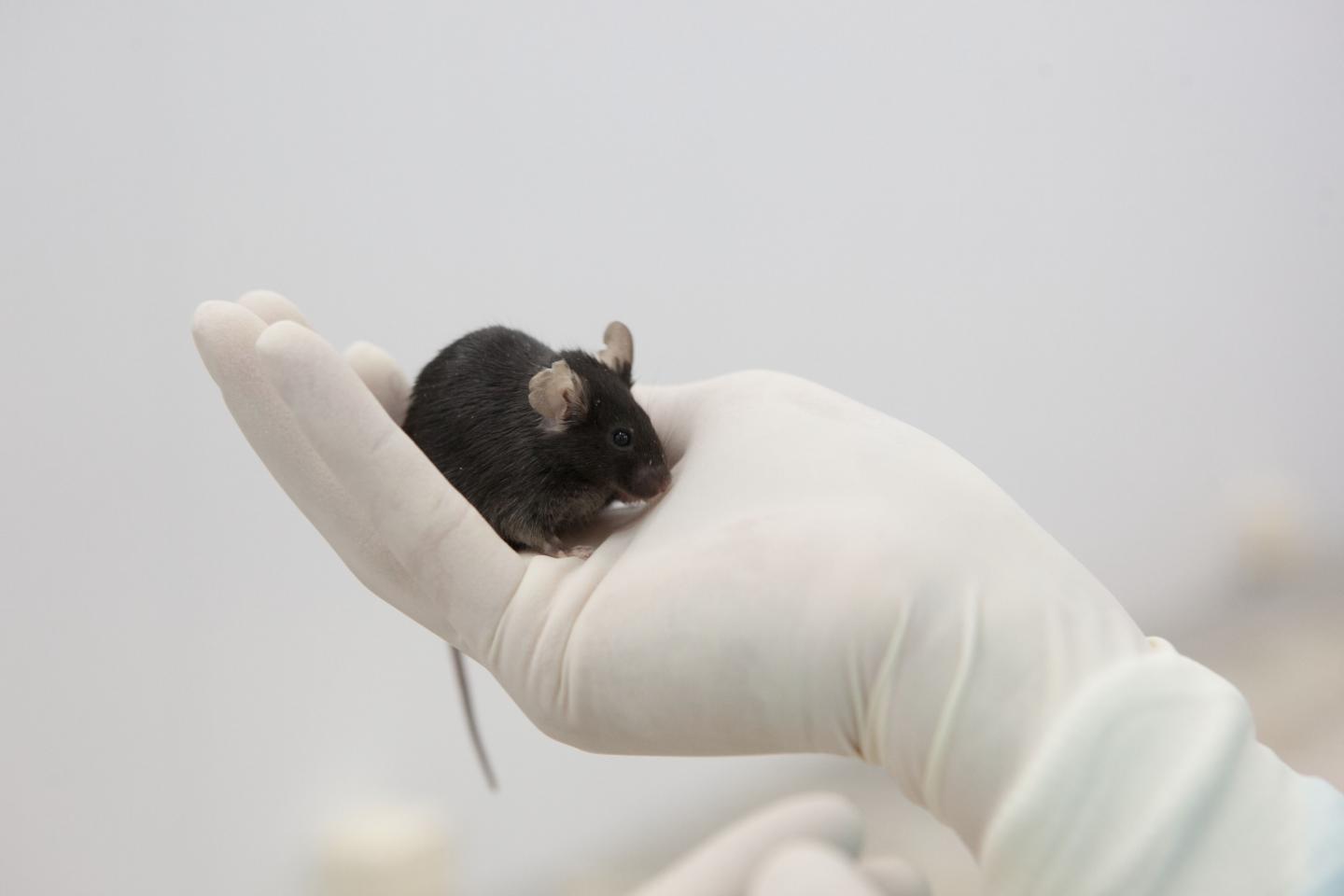

After spending a month in space, a small group of mice returned to Earth with joint problems. Now scientists are wondering what that means for humans who go to space.

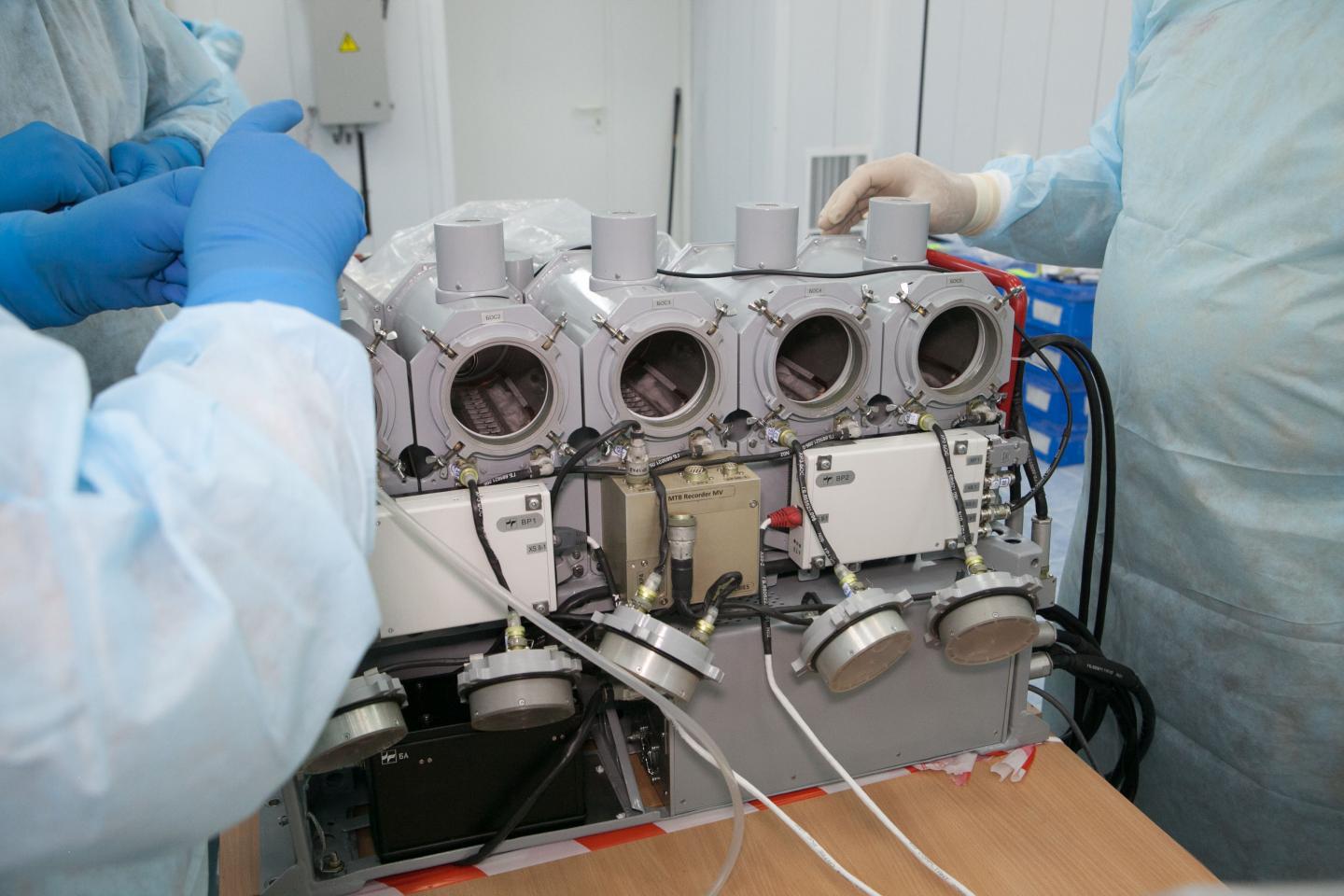

Researchers at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit studied cartilage samples collected from six mice that spent a month in space on Russia's Bion-M1 spacecraft in 2013 to see how microgravity affected their joints.

Compared with mice that stayed on Earth — which the authors refer to as the "ground control mice" — the animals that went to space had degraded joint tissue by the end of their space mission. In humans, this type of tissue damage over time can lead to osteoarthritis, or degenerative joint disease.

Related: Of Mice and Microgravity: How Rodents Adapt to Life in Space

The researchers collected two different kinds of cartilage samples from the mice: articular cartilage, which cushions bone joints, and sternal cartilage, which connects the ribs to the breastbone. They found that the articular cartilage in the space-flown mice had degraded significantly, whereas the sternal cartilage had not.

"Tissues of the musculoskeletal system — bone, muscle, tendon, cartilage and ligament — are constantly subjected to 'loading' everywhere on Earth," Jamie Fitzgerald, head of musculoskeletal genetics at Henry Ford's Department of Orthopedic Surgery and the lead author of the new study, said in a statement. "This comes from daily activities like walking and lifting, and the action of gravity pulling down on the musculoskeletal system. When that loading is removed due to weightlessness and near-zero gravity in space, these tissues begin to degrade."

Fitzgerald and his co-authors believe that the degradation observed in the joint cartilage of the space-flown mice "is due to joint unloading caused by the near lack of gravity in space," he said. In other words, joints do more work on Earth than they do in space, and when the mouse joints suddenly experienced far less physical stress in the absence of gravity, they began to deteriorate. Sternal cartilage, on the other hand, didn't seem to be affected by microgravity in the same way that the joint cartilage was.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When the mice are going about their business on Earth — whether they're walking, running, climbing or stuffing their faces with cheese — the joint cartilage "is cyclically loaded with a significant fraction of body weight," which is "almost completely unloaded in microgravity," triggering cartilage breakdown, the researchers wrote in their study. Meanwhile, the only "loading" that the sternal cartilage of a mouse experiences is from the cyclical expansion and contraction of its lungs.

"Since the mice continue to breathe in microgravity and continuously load the tissue, the difference between mechanical loading in space-flown mice and controls is minimal, and cartilage breakdown is not initiated in sternal cartilage," the study's authors wrote.

So, what does this mean for humans in space? Because this study did not involve humans, the findings don't necessarily imply that spaceflight is bad for human joints. However, the study does call attention to the fact that there hasn't been much research into the effects of spaceflight on joint cartilage. Many studies have shown how weightlessness affects astronauts' bones and muscles, but the effects on their joints are not yet understood.

"This muscle and bone loss are reversed when the astronauts return to Earth," Fitzgerald said. "What is interesting about cartilage is that it's a tissue that repairs very poorly. This raises the important question of whether cartilage also degrades in space."

If long-duration space missions are in fact bad for your joints, that didn't seem to bother NASA's record-breaking astronaut Peggy Whitson, who has spent more time in space than any other U.S. astronaut and holds the record as the oldest female astronaut. "The floating, the sleeping, just being in zero gravity — it's so much easier to move. My joints don't ache nearly as much up there," Whitson told Space.com in an interview last year. Whitson's longest single spaceflight was 289 days, and she has spent a total of 665 days in space over the course of her 15-year astronaut career.

However, damage to the cartilage may not be permanent, depending on how much time an astronaut spends in microgravity, the study's authors wrote, adding that "30 days of microgravity is insufficient for irreversible cartilage degradation." Unfortunately, most of the mice on Bion-M1 did not survive the trip back to Earth, so the researchers didn't have a chance to find out whether their joints recovered after returning.

The study was published Feb. 18 in Nature Microgravity.

- Landmark NASA Twins Study Reveals Space Travel's Effects on the Human Body

- 'Iron Man' Exoskeleton Could Give Astronauts Superhuman Strength

- Cosmic Menagerie: A History of Animals in Space (Infographic)

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.