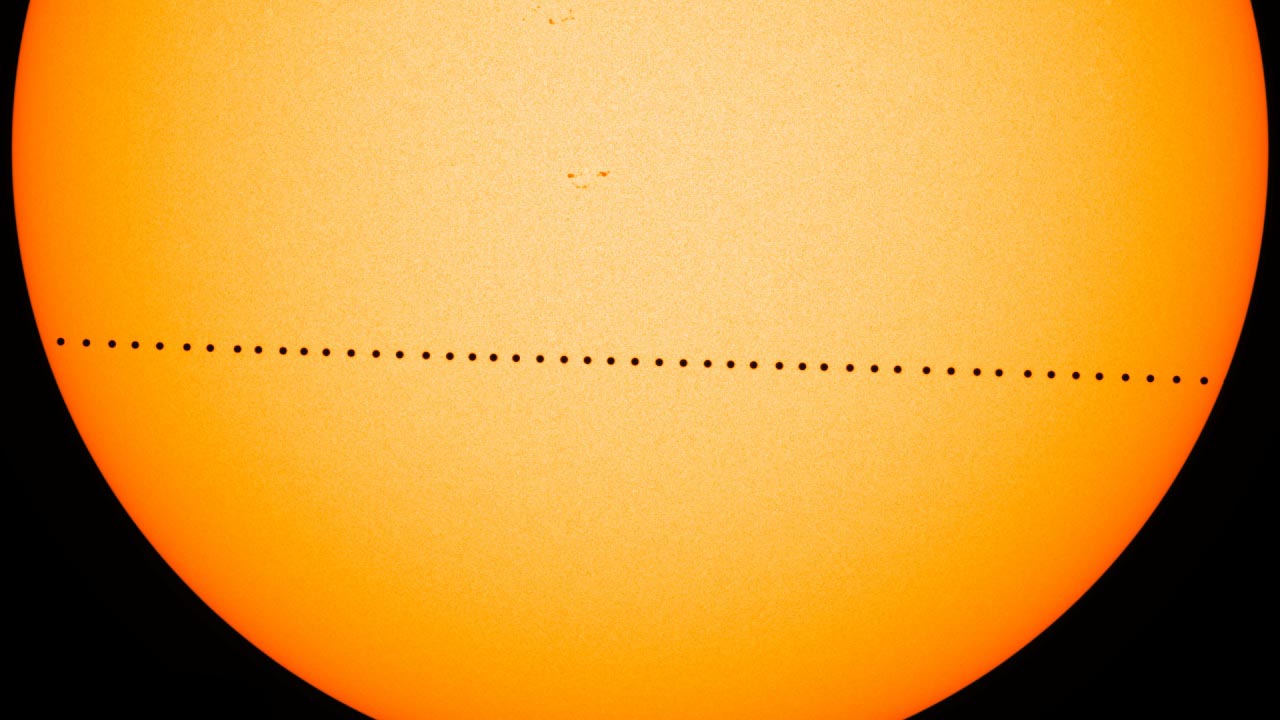

On Monday, Nov. 11, a most unusual event will take place: the transit (passage) of the planet Mercury across the sun's disk.

Such a sight is a relatively rare occurrence as seen from Earth. From our perspective, only transits of Mercury and Venus are possible. This event will be the fourth of 14 transits of Mercury that will occur during the 21st century. In contrast, transits of Venus occur in pairs, with more than a century separating each pair.

Mercury will take nearly 5.5 hours to cross in front of the sun. The transit will be widely visible from most of the Earth, including the Americas, the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, New Zealand, Europe, Africa and western Asia. It will not be visible from central and eastern Asia, Japan, Indonesia and Australia.

Related: Mercury Transit 2019: Where and How to See It on Nov. 11

The transit begins before sunrise for observers in western North America. On a map of the United States, draw a line from roughly Lake Charles, Louisiana, to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Anywhere to the west of that line will have Mercury already silhouetted against the sun's disk as it rises that morning. The transit ends after sunset for Europe, Africa, western Asia and the Middle East, with Mercury still on the sun's disk as it vanishes below the west-southwest horizon.

The entire transit will be visible from start to finish over eastern North America, Central and South America, southern Greenland and a small slice of West Africa.

First contact is when the disk of Mercury first touches the eastern (left) edge of the sun. It takes about two minutes for the disk of Mercury to completely move onto the sun's disk (second contact). The greatest transit is when Mercury will appear nearest to the center of the sun. Third contact is when the forward edge of Mercury reaches the western (right) edge of the sun. Two minutes later, Mercury completely leaves the sun's disk (fourth contact).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Below is a timetable of the various stages of the transit in five time zones:

| Header Cell - Column 0 | UTC | EST | CST | MST | PST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact I | 12:35 | 7:35 a.m. | Not visible | Not visible | Not visible |

| Contact II | 12:37 | 7:37 a.m. | Not visible | Not visible | Not visible |

| Greatest | 15:19 | 10:19 a.m. | 9:19 a.m. | 8:19 a.m. | 7:19 a.m. |

| Contact III | 18:02 | 1:02 p.m. | 12:02 p.m. | 11:02 a.m. | 10:02 a.m. |

| Contact IV | 18:04 | 1:04 p.m. | 12:04 p.m. | 11:04 a.m. | 10:04 a.m. |

A word of caution to all prospective viewers: Mercury will appear as a black dot, only about 1/194th the diameter of the sun, so a telescope magnifying at least 50 power will be needed to see it. If there are any sunspots on the sun's disk, take note of how much darker the silhouette of Mercury appears to be compared to a sunspot.

In addition, special precautions must be taken when viewing the dazzling solar disk. Be very careful to never look directly at the sun with a telescope. The visual requirements are identical to those for observing sunspots and partial solar eclipses — you need to use special solar filters to protect your eyes. It is far safer to project the sun's image through a telescope and onto a white card or screen.

If you are using a telescope with a large aperture, say 8 inches (20 centimeters) or more, you should place a circular mask in front of the objective lens or mirror to "stop down" the image, thereby reducing the amount of light and heat striking the lens or mirror.

Related: How to Make Solar Filters

Planetary peregrinations

Because Mercury's orbit is inclined 7 degrees to the plane of the orbit of Earth, most of the time when Mercury arrives at inferior conjunction — when it is between the Earth and the sun — it either will move above or below the sun and does not pass across the solar disk from our perspective on Earth. But at two points along Mercury's orbit, it will cross Earth's orbital plane (called a "node"). Earth crosses the line of nodes each year on May 8 or 9, and again six months later on Nov. 10 or 11. A transit can take place when an inferior conjunction of Mercury occurs within several days of these dates.

When a transit occurs in May, Mercury is near the aphelion point in its orbit — the point farthest from the sun and closest to the Earth. If Mercury passes centrally across the sun in May, the duration of the transit can last almost 8 hours.

When a transit occurs in November, as will be the case this month, Mercury will be near the perihelion point in its orbit — the point closest to the sun and farthest from the Earth, and where its apparent speed is faster. As such, a central transit in November has a duration of only 5.5 hours, which is pretty much what we will experience on Nov. 11. And the number of November transits outnumber the May transits by a factor of 2 to 1.

Mercury transits do not occur haphazardly. At 13-year and 33-year intervals, Mercury and the Earth return nearly simultaneously to the same points in their respective orbits, and hence a transit is often repeated after such a time interval.

So, related to the upcoming transit of Nov. 11, we can look back in time and find transits occurring 13 years ago, on Nov. 8, 2006 and 33 years ago, on Nov. 13, 1986.

Interestingly, the transits of May 9, 1970 and Nov. 10, 1973 both fell on a Saturday, while the transits of May 9, 2016 and Nov. 11, 2019 both fall on a Monday.

The next transit of Mercury will not occur until Nov. 13, 2032, but that will not be visible from North America. The next transit of Mercury visible from the United States will be on May 7, 2049.

For additional details on the upcoming transit, go to: http://www.eclipsewise.com/oh/tm2019.html

Editor's Note: Visit Space.com on Nov. 11 to see live webcast views of the rare Mercury transit as shown from telescopes on Earth and in space, along with complete coverage of the celestial event. If you SAFELY capture a photo of the transit of Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com and our news partners for a story or gallery, you can send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

- How Far is Mercury From the Sun?

- See the Sharpest-Ever View of Mercury's Transit Across the Sun

- Mercury Transit of the Sun: Why Is It So Rare?

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.