Mercury was shrinking for at least 3 billion years — and it still might be today

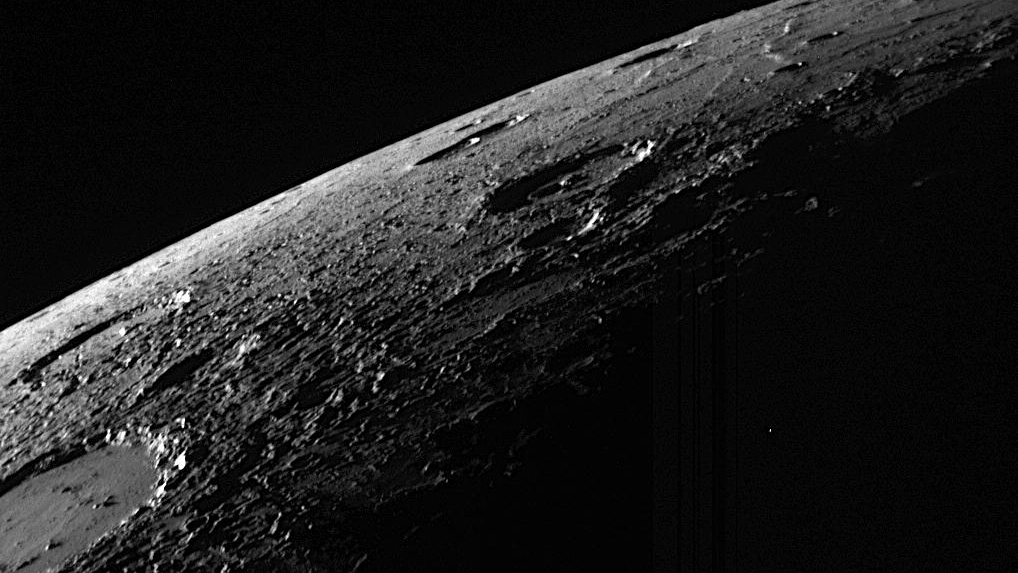

Mercury looks like a shriveled-up apple, its 'wrinkled' crust covered with scarps and grabens.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Since the 1970s, when NASA's Mariner 10 mission reached Mercury, scientists have known that the planet is shrinking as its core cools down. But while it's estimated that thermal contraction started some 3 billion years ago, it hasn't been clear whether it's still happening.

But new research conducted by scientists from The Open University in the United Kingdom suggests there's been fairly recent shrinking-based tectonic activity on Mercury — as recently as 300 million years ago. And that indicates that Mercury might still be shrinking today.

In 1974, Mariner 10 photographed miles-high slopes on Mercury's surface called lobate scarps. These scarps develop when the interior of the planet contracts as it cools; the crust of the planet then develops "thrust faults" with the reduced surface area it can cover. (It's like an old apple that's drying out — the skin develops wrinkles as the flesh shrivels up.)

Article continues belowRelated: Photos of Mercury from NASA's Messenger spacecraft

The Open University team analyzed more recent images, taken by the NASA MESSENGER spacecraft that orbited Mercury from 2011 to 2015, and discovered grabens, geological features where the ground depresses into a shallow valley along a fault. These typically occur when the crust is stretched, an indicator of the planet's shrinkage.

Because these grabens are still visible and not obscured by impact craters or the ejected debris from them (it forms in a process called "impact gardening"), the team surmised the age of the grabens to be approximately 300 million years old. Older geologic features like the scarps are heavily altered by impact gardening.

While it's difficult to say if Mercury is still shrinking right now, 300 million years ago is fairly recent in geological terms, suggesting the possibility that its core may not have cooled completely and might still have some shrinking to do.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The grabens will be more closely observed on an upcoming joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) called BepiColombo. The spacecraft launched in 2018 and is due to enter Mercury's orbit in late 2025, where it will collect new data.

The team's findings were published on Oct. 2 in the journal Nature.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.