Mariner 10: First Mission to Mercury

Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft to visit Mercury. It showed close-up pictures of the sun's closest planetary neighbor and also did investigations of Mercury's environment and surface.

The spacecraft had other, lesser-known milestones as well. It was the first spacecraft to slingshot past one planet on its way to visit another. Mariner 10 was also the first probe to visit two planets in one mission.

Despite several mechanical problems during the mission, NASA persevered and got a lot of science out of the struggling spacecraft. Mariner 10 thus became a demonstration of how to adapt missions on the fly, which is an important skill NASA still uses today. The plucky spacecraft even has a postage stamp to commemorate the mission.

Interplanetary mystery

When Mariner 10 lifted off from Cape Canaveral on Nov. 3, 1973, very little was known about our neighbors in the solar system. Mariner 10 would only have quick flybys past Venus and Mercury, to be sure. But there was a lot that could be glimpsed even in a short span of time.

Astronomers were curious about Mercury's high density, and what lay inside the planet's core. The running hypothesis, according to NASA, was that the planet's density was due to a high concentration of metals. But there were questions about the exact composition of the core, and how that core was put together during the early days of Mercury's formation.

As for Venus, scientists wanted to delve deeper into how the planet interacted with the solar wind. On Earth, the magnetic field buffers us from particles streaming out from the sun. The sun's energy, when it hits Earth, forms a shockwave. Some particles flow along magnetic field lines and form auroras at the Earth's poles. On Venus, though, scientists didn't fully know how the sun's particles affected that planet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

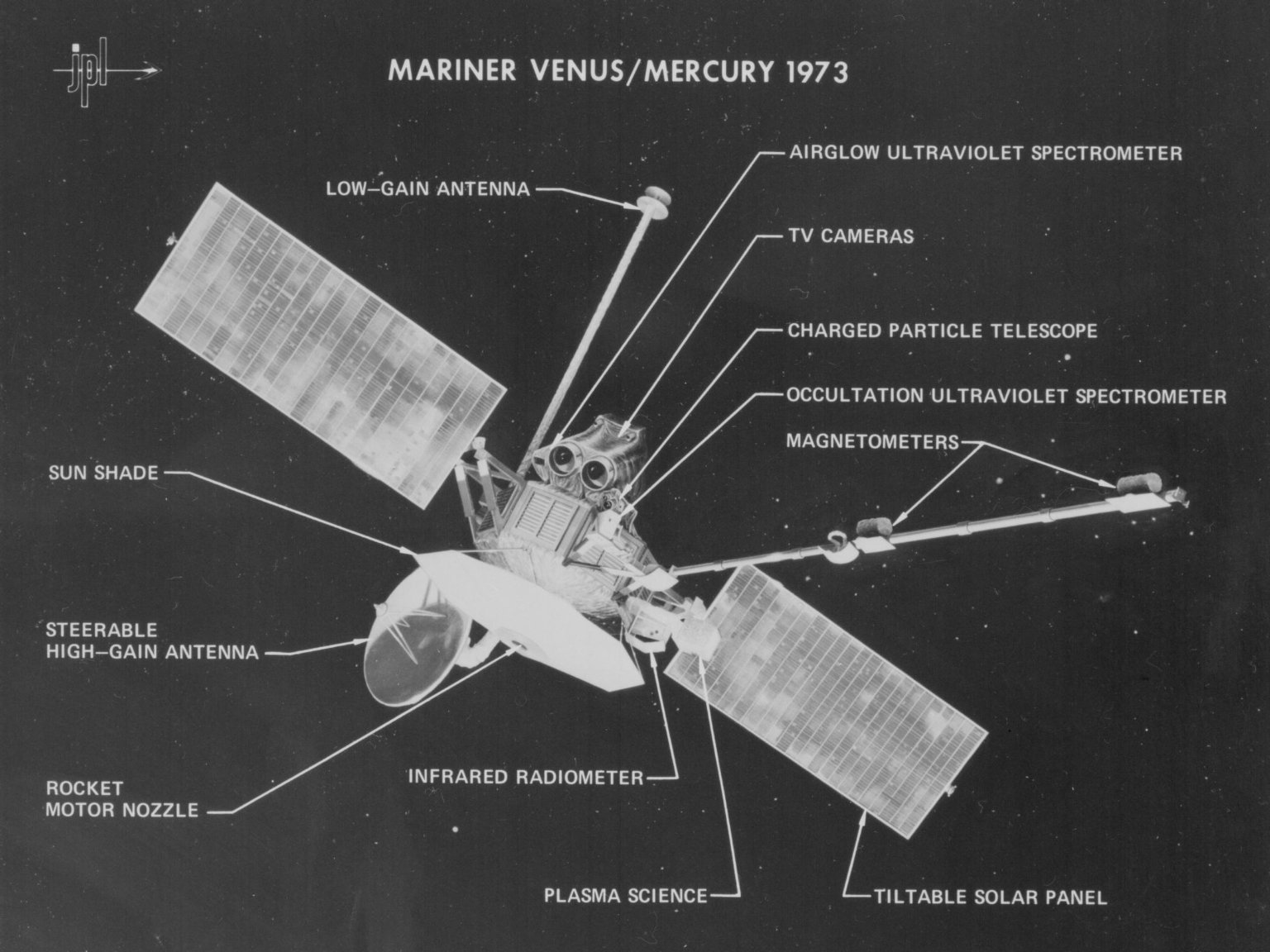

Mariner 10's mission would, with any luck, shed some light on these mysteries. The spacecraft cost $100 million in 1973 dollars, the equivalent of more than half a billion dollars in today's money. Many scientists' hopes were riding on the 1,045-pound spacecraft.

Troubles en route to Venus

Mariner 10 kept spacecraft planners busy as it moved toward a planned rendezvous with Venus. NASA needed not only to keep the spacecraft healthy, but also to make sure it was on the right trajectory to slingshot around the planet to make it to Mercury.

It was only a three-month trip to Venus, but it probably felt like a lot longer to the people managing Mariner 10 through various mechanical difficulties. Shortly after launch, NASA discovered that some television camera heaters were not turned on. Mission control sent a command to deactivate and then reactivate these heaters, but was not successful. Luckily for NASA, the camera temperature stabilized before it got too cold to operate.

There was a backup spacecraft available to launch if the cameras became too cold. But that would have been an expensive solution.

Science experiment issues were not the only problems besetting Mariner 10 as it flew toward Venus. The flight data system kept resetting itself. In January, the spacecraft switched itself to a standby power system, an error that couldn't be reversed.

Communications and data transmissions became rocky when the high-gain antenna developed some problems. Worse, Mariner 10 also lost 16 percent of its attitude control fuel on Jan. 28 in one spectacular purge caused by a mechanical problem.

"The spacecraft seemed to be behaving quite neurotically and confounding its designers and controllers," a NASA historian wryly wrote in "The Voyage of Mariner 10."

Controllers went to a backup option to align Mariner 10 for its scoot by Venus, and succeeded in performing the slingshot. The video camera heaters resurrected around this time, providing another bright spot in an otherwise tumultuous few months. Mission controllers elected not to use the heaters for the time being, as the heat from the sun was enough to keep the cameras functional.

Glimpses of Venus

Mariner 10 gave scientists a much better understanding of how Venus' magnetic field performs. As it turned out, the planet only had a twentieth of the strength of Earth's magnetic field, according to Mariner 10 measurements. This means it can't shield Venus to the same extent that we see here on Earth. For example, the large clouds of particles seen in Earth's radiation belts don't congregate near those of Venus.

The spacecraft also measured a bow shock of radiation as the solar wind hit the area around Venus, which was seen before with the Mariner 5 and the Soviet Union's Venera 4 spacecraft. At the time, though, scientists didn't quite understand how this was happening.

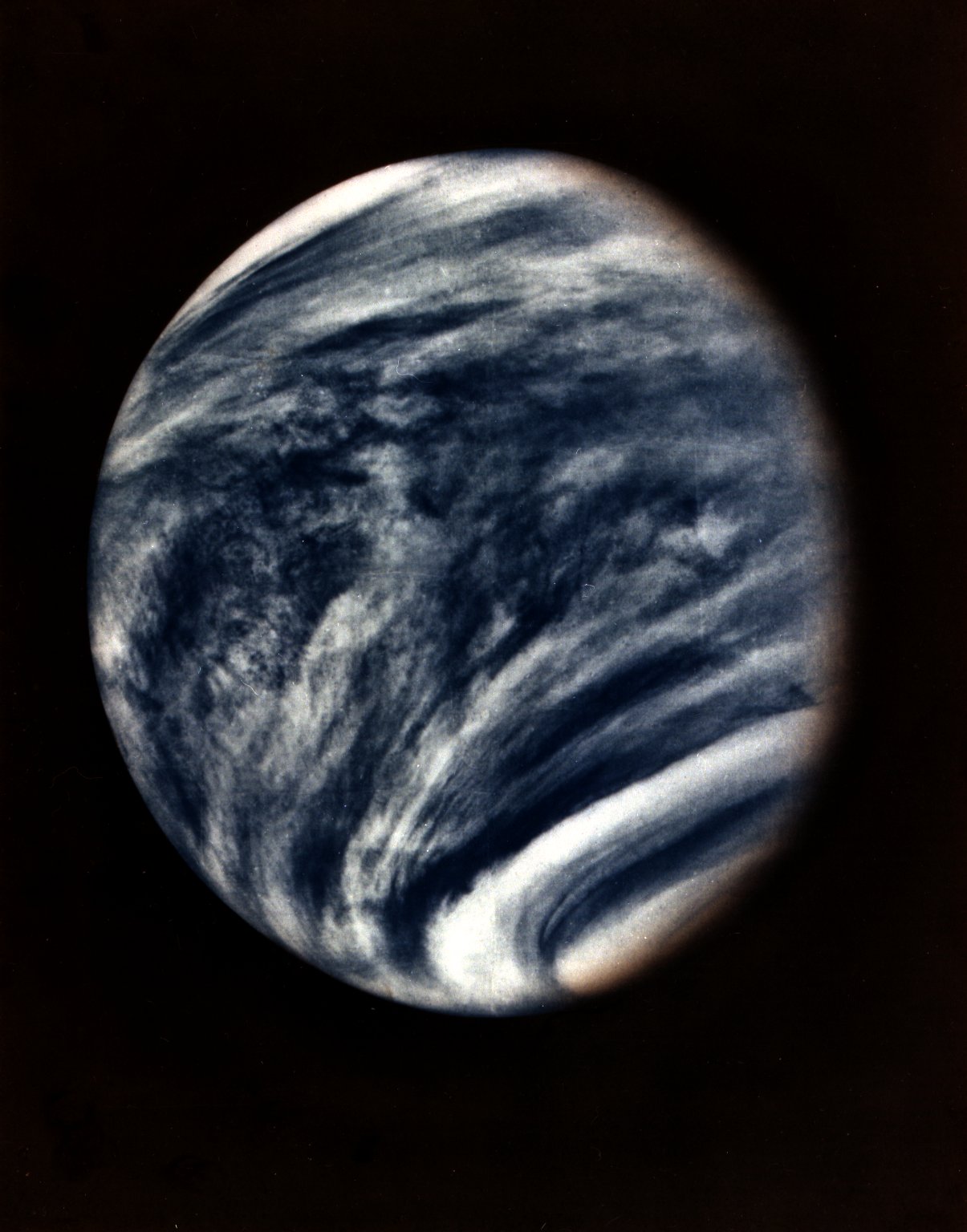

Mariner 10's visible light pictures of Venus didn't show much variation, which proved the planet was socked in by a thick cloud layer. In ultraviolet light, though, the spacecraft could see swirls and patches. Venus apparently had an active atmosphere.

The spacecraft was well on its way to Mercury now, but it continued to cause headaches for the engineers back on Earth. On Feb. 18, 1974, the spacecraft got confused between a bright particle and its navigation star, Canopus.

Controllers had seen this problem since launch, but on this particular occasion the spacecraft was confused for nearly two hours and spent valuable fuel. The Canopus problems increased to 10 a week by the end of that month, from perhaps one or two a week in the time after launch.

Mercury at last

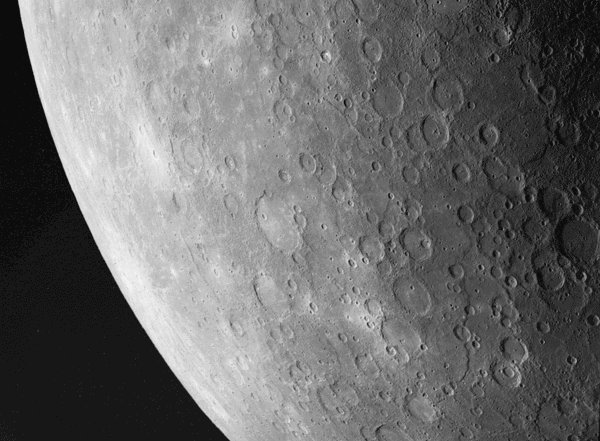

The efforts of Mission Control weren't in vain, though. Mariner 10 made it past Mercury on March 29, 1974, the first of three passes. (The other two were on Sept. 21, 1974, and March 16, 1975.)

Mariner 10 showed a bleak planet that looked similar to the surface of the moon. Craters and bare ground showed up in the pictures. One significant difference was the presence of scarps, which to scientists suggested that the planet's crust might have shrunk at some time during its history.

Another surprise came when Mariner 10 took measurements of the magnetic environment around Mercury. The instruments showed that Mercury had a small magnetic field that is about one-sixtieth as strong as that of Earth's. Scientists believed that Mercury's magnetic field came from within the planet rather than being generated through the planet's interaction with the solar wind.

Mariner 10 detected a faint helium atmosphere around the solar system's innermost planet. Also, the spacecraft was used to test out new navigational techniques that mission planners would be able to use on future spacecraft.

The aging spacecraft had several other difficulties during the later passes, including losing much of its attitude gas in attempts to lock on to Canopus. NASA continually had to make changes to Mariner 10's mission to get the most science out of the spacecraft's passes by the closest planet. But it showed us quite a bit despite its problems.

NASA commanded Mariner 10 to turn off its transmitter on March 24, 1975, after the spacecraft ran out of fuel. Today, Mariner 10 is still presumably orbiting the sun, but we haven't heard anything from the spacecraft since then.

Despite Mariner 10's troubles, a lot of science was performed. It provided the only glimpse of Mercury we would see for a generation, until the MESSENGER spacecraft flew that way for the first time in 2008.

— Elizabeth Howell, SPACE.com Contributor

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.