Why the James Webb Space Telescope's sunshield deployment takes so long

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope is three days into the deployment of its massive sunshield — and it still has about three days to go.

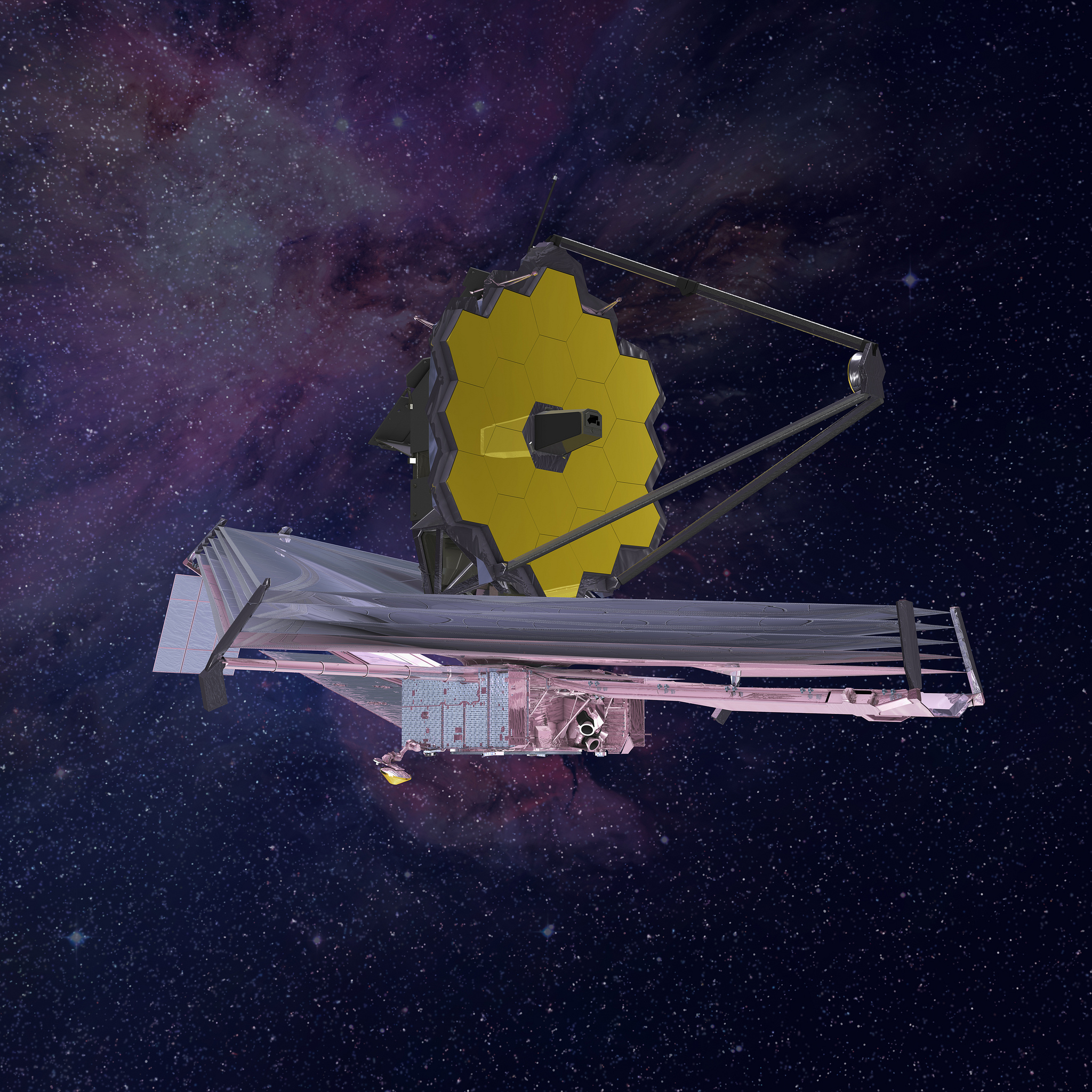

The $10 billion Webb launched on Christmas Day (Dec. 25) to seek out heat signals from the early universe. To pick up these faint signals, the observatory's optics and instruments must be kept extremely cold, and that's where the sunshield comes in.

The five-layer structure will reflect sunlight and radiate heat extremely efficiently, allowing Webb to maintain its "cold side" at a frosty minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 223 degrees Celsius) or so, if all goes according to plan. The observatory's sun-facing "hot side," by contrast, will be around 230 degrees F (110 degrees C), NASA officials wrote in a Webb sunshield explainer.

Article continues belowLive updates: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope mission

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

The kite-shaped sunshield measures 69.5 feet long by 46.5 feet wide (21.2 by 14.2 meters). That's far too large to fit inside the payload fairing of any currently operational rocket, so the structure lifted off in a highly compact configuration and must now unfurl in space.

That operation is incredibly complex, involving many different nail-biting, time-consuming steps.

"Webb's sunshield assembly includes 140 release mechanisms, approximately 70 hinge assemblies, eight deployment motors, bearings, springs, gears, about 400 pulleys and 90 cables totaling 1,312 feet [400 m]," Webb spacecraft systems engineer Krystal Puga said in "29 Days on the Edge," a video about Webb's deployments that NASA posted in October.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"All this just to keep the sunshield under control as it unfolds," added Puga, who works for the aerospace company Northrop Grumman, the prime contractor for the Webb mission.

That unfolding began on Tuesday (Dec. 28) with the sequential deployment of two pallets that contain the sunshield structure. Webb took the next step on Wednesday (Dec. 29), extending its Deployable Tower Assembly, a move that, among other things, created room for the sunshield membranes to unfurl.

Two more milestones came on Thursday (Dec. 30): Webb released the cover that had protected the sunshield during ground operations and launch and also deployed its "aft momentum flap," which will help the observatory maintain its orientation and position without using too much fuel.

"As photons of sunlight hit the large sunshield surface, they will exert pressure on the sunshield, and if not properly balanced, this solar pressure would cause rotations of the observatory that must be accommodated by its reaction wheels," NASA public affairs specialist Alise Fisher wrote in a blog post on Thursday. "The aft momentum flap will sail on the pressure of these photons, balancing the sunshield and keeping the observatory steady."

The deployment action, which you can follow here, will keep on coming. Webb is expected to unfurl its five sunshield membranes on Friday (Dec. 31), which it will achieve by extending two booms. Mission team members will get the membranes up to their proper tension over the weekend, potentially wrapping up this procedure — and sunshield deployment overall — as early as Sunday (Jan. 2).

The focus will then shift to Webb's primary and secondary mirrors, both of which are scheduled to be completely deployed by Jan. 7 or so.

NASA officials and Webb team members have stressed, however, that these timelines are flexible. Some steps may take longer than anticipated, so don't panic if the observatory doesn't seem to be hitting its marks exactly (though it has done so quite nicely thus far).

We should all also take a moment to celebrate what Webb has accomplished so far, and to wish the mission team luck on the steps that remain.

"The Webb observatory has 50 major deployments … and 178 release mechanisms to deploy those 50 parts," Webb Mission Systems Engineer Mike Menzel, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in "29 Days on the Edge."

"Every single one of them must work," Menzel said. "Unfolding Webb is hands-down the most complicated spacecraft activity we’ve ever done."

These deployment steps are occurring as Webb is cruising to its deep-space destination, a gravitationally stable spot 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from our planet called the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2). The observatory will get there about 29 days after launch, slipping into orbit around L2 with a precise engine burn.

But Webb won't be ready to start observing the cosmos as soon as it arrives — not nearly. It'll take about five more months to precisely align the 18 segments that comprise the telescope's 21.3-foot-wide (6.5 m) primary mirror and calibrate its four scientific instruments. Regular science operations are expected to begin in late June or early July 2022.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.