James Webb Space Telescope catches 'imposter' galaxies red-handed

Dusty, red galaxies could be posing as extremely high-redshift galaxies in JWST's images, astronomers warn.

Dusty, star-forming galaxies that existed a billion years after the Big Bang could be masquerading as the record-breaking galaxies discovered by NASA's new space telescope that have been thought to date to even earlier times.

In the weeks since the first batch of science data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was released, astronomers have been reporting a steady stream of candidate galaxies far more distant than any seen before the launch of NASA's flagship space telescope. If measurements are correct, then these galaxies existed just 200–300 million years after the Big Bang, but now two independent teams of astronomers are calling at least some of them into question.

The more distant a galaxy is, the earlier in the universe we are seeing it and the more its light has been stretched by the expansion of the universe, resulting in blue and ultraviolet light from hot young stars appearing as infrared to us after traveling for over 13.5 billion years. It's why we need the infrared capabilities of JWST to see them. Astronomers call this effect 'redshift,' and the greater the redshift, the more distant the galaxy and the earlier in the universe's history we are seeing it.

Gallery: James Webb Space Telescope's 1st photos

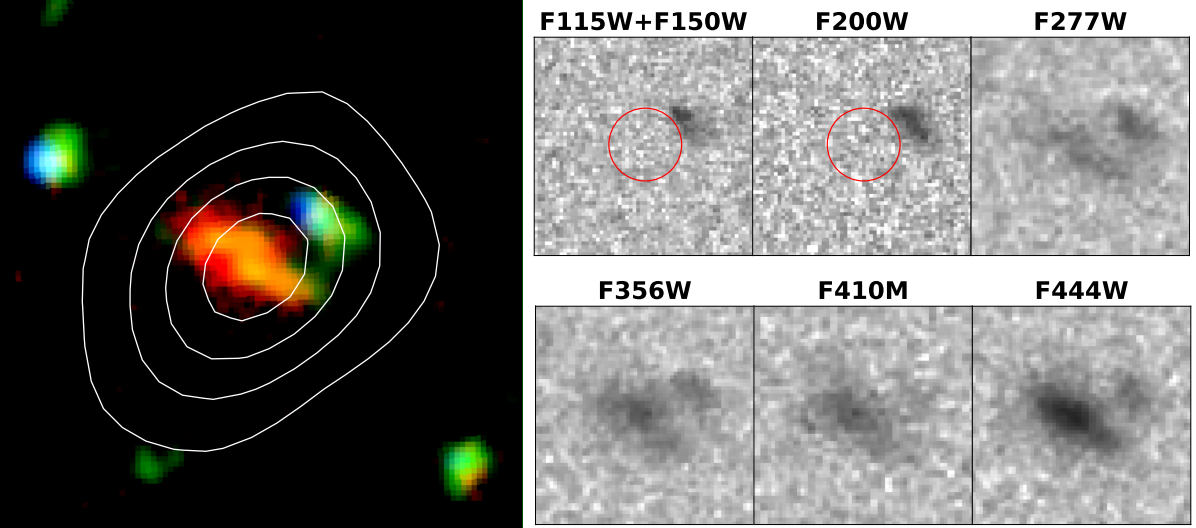

However, according to the two teams at least one of these galaxies, CEERS-DSFG-1, is an imposter.

Based on how red the galaxy appears to JWST, astronomers had determined a redshift of 17 to 18 for CEERS-DSFG-1, placing it just 220 million years after the Big Bang. Yet a team led by Jorge Zavala of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan used the NOEMA (Northern Extended Millimeter Array) submillimeter telescope in France to detect this distant galaxy and find that it contains huge amounts of dust.

Dust absorbs shorter, bluer wavelengths of starlight while allowing longer, redder wavelengths to pass, meaning that a dusty galaxy can mimic the redness of a higher redshift galaxy. Once this was taken into account, Zavala's team calculated a redshift of just 5 for CEERS-DSFG-1, placing it some 12.5 billion years ago, 1.3 billion years after the Big Bang. It's still old and far away, but not to any record-breaking length.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Far from being bad news, discovering more galaxies at redshift 5 is actually crucial for a better understanding of how galaxies grew during that period in the history of the universe.

Interstellar dust is a by-product of the cycle of star-birth and death. To produce enough dust to sufficiently redden its light, CEERS-DSFG-1 must be producing stars at a rate of 150 solar masses per year, 50 times greater than the rate at which stars are currently forming in our Milky Way galaxy.

According to astronomers' models, galaxies with so much dust and star formation could have existed 1.3 billion years after the Big Bang, but they are thought to have been relatively rare.

"If we found a large number of these galaxies with JWST, the observations would start to be in tension with the models," Zavala told Space.com.

It might just be that such galaxies are more common than previously thought. Zavala's team also followed up on two more galaxies with claimed high redshifts — Maisie's Galaxy at a redshift of 14.3 placing it 280 million years after the Big Bang, and a redshift 16.7 galaxy found just 250 million years after the Big Bang.

Their observations of Maisie's Galaxy found no evidence for large amounts of dust. "We can rule out that Maisie's Galaxy is a bright dusty galaxy at lower redshift, which, indirectly, supports the idea that this galaxy is indeed at a very high redshift," said Zavala.

They did, however, find question marks over the redshift 16.7 galaxy.

"We found an alternative scenario to explain its colors as observed by JWST," said Zavala, adding that rather than being at redshift 16.7, it "implies that this galaxy is at redshift 5."

Callum Donnan, of the University of Edinburgh, who led the team that found the redshift 16.7 galaxy, disagrees with Zavala's assessment.

"Dusty lower redshift solutions were a concern," he told Space.com. "We therefore explored this, [but] the galaxy candidate at redshift 16.7 is especially unlikely to be a dusty, lower redshift galaxy because it has a blue ultraviolet continuum and no significant detection at submillimeter wavelengths."

However, Zavala says that there is some tentative observational evidence at submillimeter wavelengths to support the claim that the galaxy is at redshift 5. His team used the SCUBA2 instrument on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii to observe the region of sky that the redshift 16.7 galaxy resides in, and they found an anomalous source of submillimeter-wavelength in the vicinity, which could be emission from dust in the galaxy. However, given the faintness and tiny size on the sky of the galaxy, Zavala's team cannot confirm that the galaxy and the submillimeter source are one and the same.

Additional evidence has come from a second team, led by Rohan Naidu of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who also concluded that the redshift 16.7 galaxy is at redshift 5, albeit in a different way to Zavala's team. They found that the redshift 16.7 galaxy's near neighbors in the sky are all galaxies at about redshift 5, and together they form a very young proto-cluster that the redshift 16.7 galaxy is in the middle of. The inference is that the redshift 16.7 galaxy is part of this burgeoning galaxy cluster, rather than a very high redshift galaxy.

For the moment, nobody knows for sure the true redshifts of these objects. Everyone is now waiting for spectroscopic measurements of the redshifts — identifying how much individual lines in a galaxy's spectrum have been redshifted, rather than basing the redshift on the galaxy's color — for a conclusive determination one way or the other. According to Zavala, astronomers are pushing hard to get these vital follow-up observations not only with JWST, but other powerful telescopes around the world, including ALMA, the Keck Observatory and others.

This all begs the question, should we be skeptical of high-redshift claims until the spectroscopic redshifts have been obtained?

"Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence," said Zavala. "While a lower redshift dusty galaxy might not explain all these detections, when the possibility remains open, we need to first rule it out before claiming the opposite."

The paper by Zavala et al has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal, and the paper by Naidu et al to The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify references to specific galaxies. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.