Fortnite flashback: Just how accurate was the black hole that launched Chapter 2?

It looks like Epic Games may have nailed it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

When Fortnite launched its latest incarnation — Chapter 2 — last fall, it did so with cosmic flair: A cosmic event that destroyed online game's island battleground and left a serene black hole in its wake.

As Season 1 of Fortnite's Chapter 2 ends and a new era begins today (Feb. 20), we were wondering: Just how good was the game's version of a black hole, given that scientists recently captured the first photo of an actual black hole last year?

It turns out, Fortnite's black hole is surprisingly accurate, says one member of the project that took that first-ever image of a black hole. But don't ever expect to get as close to a black hole as Fortnite's point-of-view offered and survive.

Fortnite is an online battle royale video game that has become very popular across the world since its release in 2017. Players got a big surprise in October 2019 when a black hole appeared to end the game, transforming its island battleground into nothingness for a few days until Chapter 2 Season 1 began.

The illustration of the black hole was nice to watch, if not frustrating for Fortnite fanaticse. One researcher thinks the Epic Games team behind Fortnite did a decent job at capturing the essence of a black hole.

Related: The strangest black holes in the universe

First: A black hole primer

Joseph Farah is a research fellow at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was part of the team that produced the first-ever image of a black hole in 2019, and he continues to collaborate with the project, known as the Event Horizon Telescope. So, he knows a thing or two about what black holes look like.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Two areas of focus for Farah are imaging and modelling. When researchers try to create an image, they assume nothing and work to create a true picture from the data. And when they develop models, they make assumptions about the physics of a black hole to then learn details about the object. For example, by assuming Einstein's theory of general relativity to be true, researchers can ascertain information about the black hole, like its mass and inclination, Farah said.

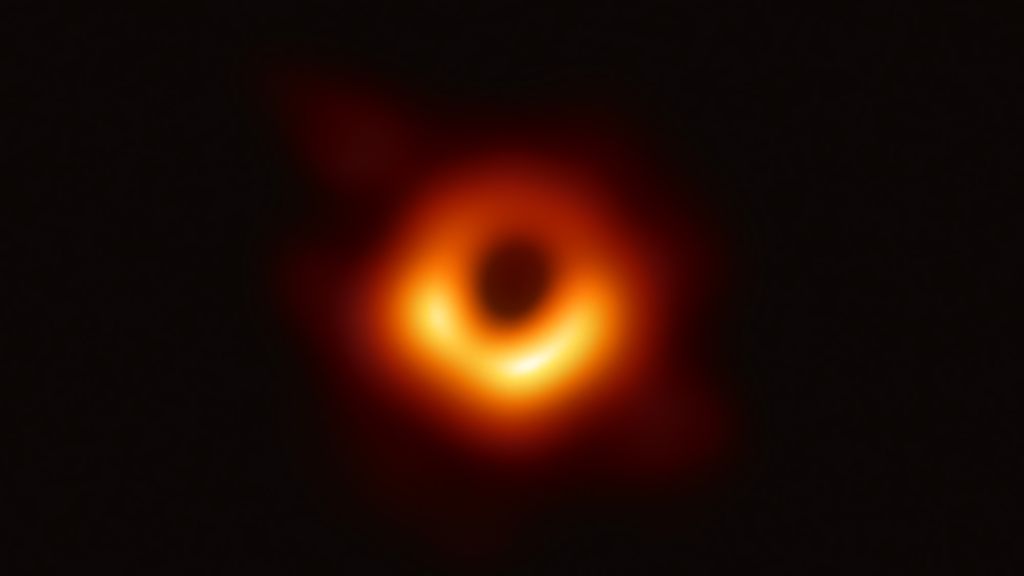

The iconic first image of a black hole features the behemoth M87, a gravitationally-dense structure which harbors about 6.5 billion times more mass than Earth's sun. One year later, M87 continues to be very important for the EHT team. By comparing future data to the original image, they can test the functionality of the telescope.

And with the help of some additional gadgets, the picture of a black hole could have a higher resolution. One way to make the image less fuzzy is by using satellites into space to collect observations via VLBI, or very long baseline interferometry.

Currently, EHT works as a worldwide collaboration of radio telescopes. The collective telescopic network has a "lens" the size of planet Earth. By sending VLBI spacecraft into orbit, researchers can potentially double, triple or quadruple the baseline, or the distance between two telescopes in the array. Significantly increasing the longest baseline would have a big impact on their image resolution, because you make the lens of EHT much wider than what the telescope network currently has.

The Fortnite black hole

So then, how accurate is the Fortnite black hole?

"It was surprisingly accurate," Farah said.

For example, the wisps around the Fortnite black hole appear in actual EHT simulations. As material gets closer to the black hole, it speeds up, then heats up, causing the glowing region around the black hole.

"The wisps themselves are the direct result of the magnetic field, of the magnetic turbulence around the black hole," Farah said.

"How these wisps form and what they mean about the magnetic field of a black hole is actually a strong point of debate," Farah added. "We sort of have an idea, but we don't understand it fully. It's something that we want to test more."

The appearance of the black hole looks accurate, but that's about it.

Remember those radio telescopes across the planet that produce the image of a black hole? Well, their job is to detect wavelengths that human eyes can't see. So, if you were inhabiting your Fortnite avatar, you wouldn't see this shadow. You wouldn't see anything but a washed-out color all around you.

Related: Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?

"Even if you were close enough to have the shadow be on a resolvable scale, it would just look washed out in optical and infrared [wavelengths]. It would just be glowing from all the gas even farther away from the black hole. That’s the reason we observe at these longer [radio] wavelengths; because those are the wavelengths that can escape from the areas closest to the black hole," Farah said.

Surprise: You can't survive near a black hole

And it might go without saying, but a human being could not survive being that close to a black hole.

"If you were close enough to the black hole to sort of see that Fortnite image, I think you probably wouldn't survive. Yeah, I don't think you'd have much of a chance," Farah said.

"The gravity, even at that range, would be like ridiculously strong. You know, we're not really built for pressure. If we go down too far in the ocean, you start having health problems pretty quickly. If you, you could probably get into an orbit maybe close enough where you can counteract some of the gravitational force if you are moving fast enough. I don't know what that would do medically to you. I have a feeling that being close to a black hole would not be healthy."

And while the next installment of Fortnite did not start with a journey through a wormhole (Chapter 2 Season 2 is all about secret agents, gold and the Midas touch), that'd also be a heavy dose of science fiction.

Wormholes present a lot of problems, Farah said.

Their novel characteristic is that they would provide a way to travel between to different points in space-time faster than you could normally over space, he said. But there is zero experimental evidence for them. If scientists one day did observe a wormhole, it would be "inherently unstable," Farah said, and would require matter that doesn't exist (i.e. matter with negative mass) to stabilize it.

And then, even if you did manage to find a way to stabilize a wormhole, pushing something through a wormhole would cause the wormhole to destabilize and collapse.

So, there you have it. Fortnite's black hole nailed the look of actual black holes. And while Chapter 2 Season 2 may not have much space in it, when it comes to black holes, Epic Games was spot on.

- Star Trek Online's 'Legacy' update lets you live your 'Star Trek: Picard' dreams

- Why a robot janitor is 'The Outer World's' best companion

- Mars monsters inspired by Lovecraft's Cthulhu haunt eerie 'Moons of Madness' game

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.