Imagining early Earth as an exoplanet can help us search for alien life, scientists say

"Molecular time travelers" are one piece of the puzzle to understand whether there's life beyond Earth.

What if we thought of our ancestors as a form of alien life?

Such an exercise might be one of the ways that we can test our assumptions about how habitable conditions arise and are sustained, and perhaps even about how life evolved from simple microbes into something more complex, reporters heard during an online presentation May 18 held by the American Geophysical Union as part of its astrobiology-focused AbSciCon conference.

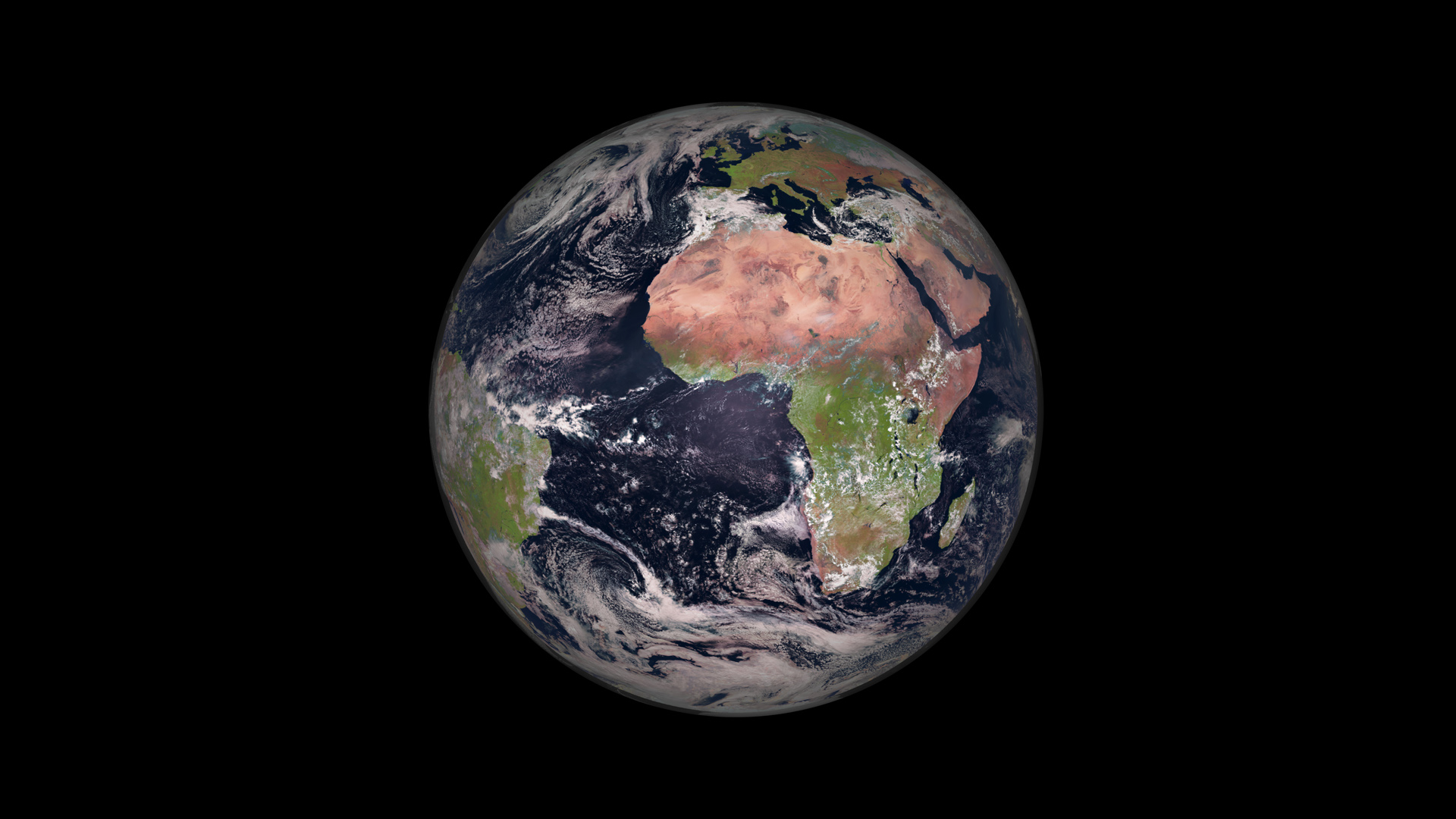

"The ancient Earth is kind of an exoplanet," said Aaron Goldman, a biology professor at Oberlin College who studies the emergence of life. He said that comparison works because the early Earth is so different than what we know of today.

Related: Earth's atmosphere is full of microbes. Could they help us find life on other worlds?

Looking at Earth's life history, he said, provides an accessible framework to understand how microbes may behave on other planets, although such avenues might not tell us the whole story. But through his research on evolution, Goldman and collaborators are trying to understand scenarios by which life may arise.

Today's life, he says, is cellular and based on DNA, but neither cells nor DNA were present in the earliest forms of life on Earth. By association, "these were things that had to evolve in early evolutionary history," he said. "So understanding how and why these characteristics of life evolved on early Earth can inform whether or not we would expect the same things to be present in extraterrestrial organisms."

Assuming life evolved elsewhere in ways similar to on Earth is only one way scientists approach astrobiology, however. Heather Graham, an organic geochemist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, focuses on molecules instead.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One methodology by which her group does these studies, she said, is examining molecular complexity and then expanding that to populations (or assemblages) of molecules. "We can say how likely it was that that molecule or that assemblage would have originated from a living system," Graham said.

"We're also doing some work looking at how to employ scaling laws, which we think are very universal to life," she said. Elemental stoichiometry, which focuses on the balance between different elements, is one possible tool that allows scientists to see how organisms build molecules and in turn learn about metabolism. The technique, she said, may help "divorce ourselves" from assumptions about how life began.

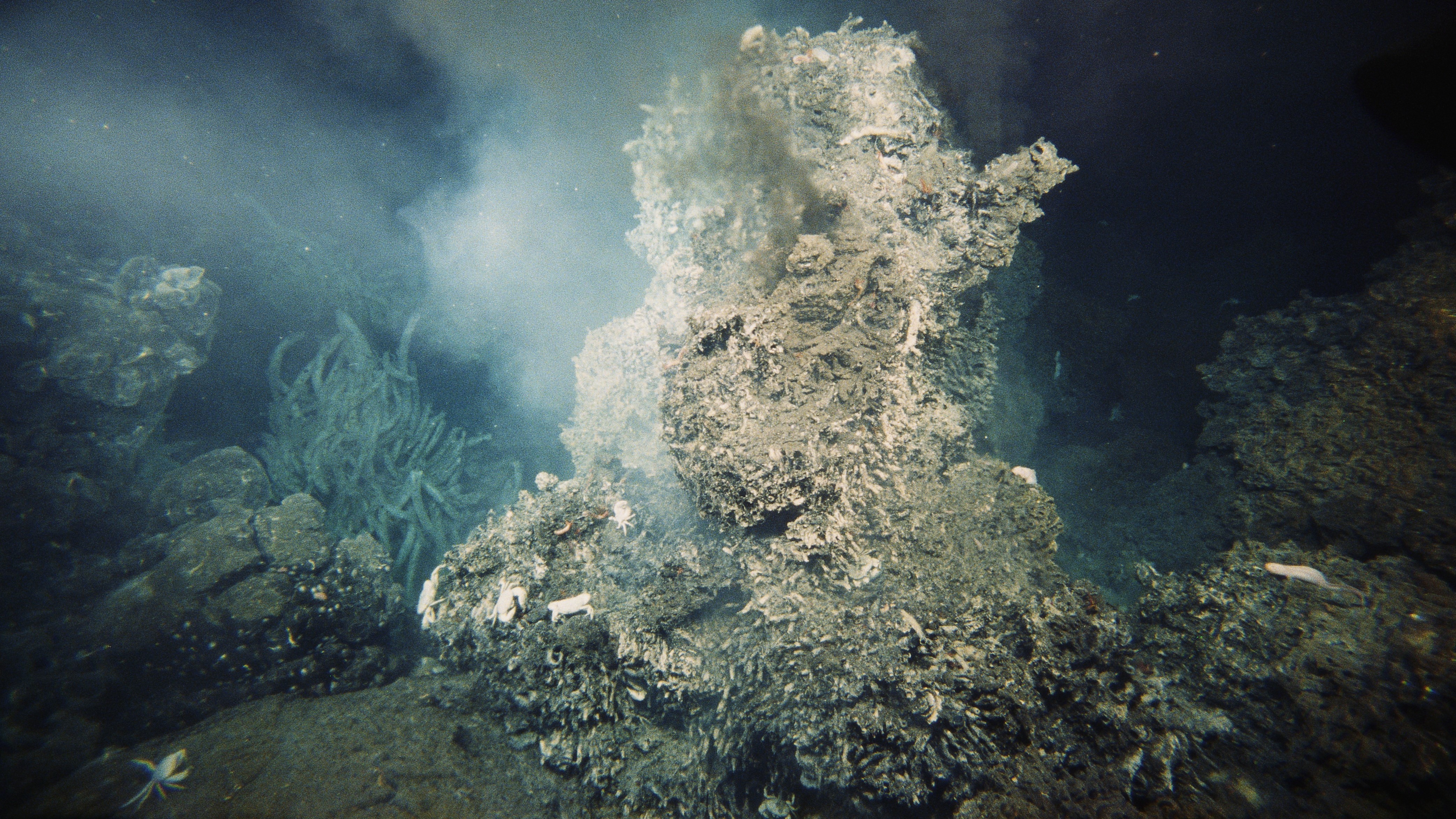

Adrienne Kish, a microbiologist with the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, said we also need to remember how commonly life can arise in places on Earth that are utterly inhospitable for humans. An example is hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean.

"I am in the lab and learning exactly the molecular machinery of what's the living environment that the human body cannot simply support," she said. "We're looking really deeply at the machinery of life at a very basic level, and then trying to imagine now: is this something similar that could have arisen on another planet? What does this tell us about our own planet, and potential for life someplace else?"

Betül Kaçar, a biologist at University of Wisconsin-Madison, emphasized that life is innovative and finds "really creative ways to make use of what is in its surroundings." Kaçar's lab seeks to create experimental tools to recreate ancient DNA.

"It goes back to thinking about our past of our planet as an altogether alien environment," Kaçar said, but emphasized our lack of understanding at the molecular level impedes us.

"We like to think of ourselves as molecular time travelers. We resurrect ancient DNA inside modern organisms, to reprogram modern bugs to behave like they did once in the past. So we really want to understand this dance between life itself and the environment."

Being a biologist, Kaçar said, is a vocation where you can study life across the universe. "Astrobiologists are going to change that," she said of the field of biology. "And that makes our job a really, very special one."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.