Scientists Spot Two Dead Stars Locked in a Dizzying Dance

Bright and weird, two white dwarfs orbit every 7 minutes.

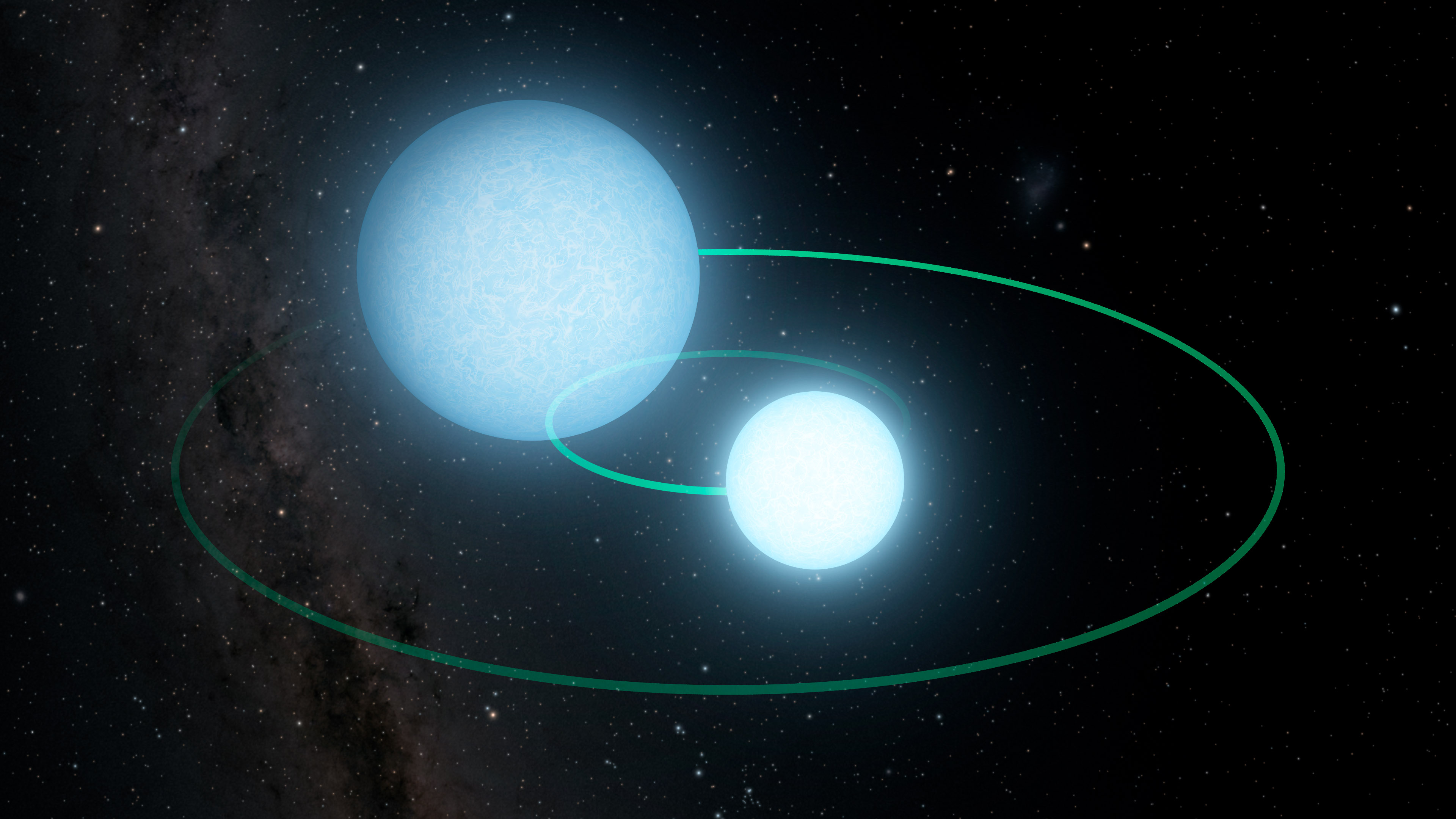

Two dead stars have been spotted rapidly whirling around one other, one eclipsing the other every 7 minutes.

At the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) spends its nights scanning the sky for bright things that disappear and reappear. Caltech graduate student Kevin Burdge was combing through months of ZTF data and noticed a peculiar blinking pattern. Burdge, the lead author of a new study explaining this discovery, found that the pattern is created by a pair of white dwarfs — what stars like the sun become after they "die," or run out of fuel.

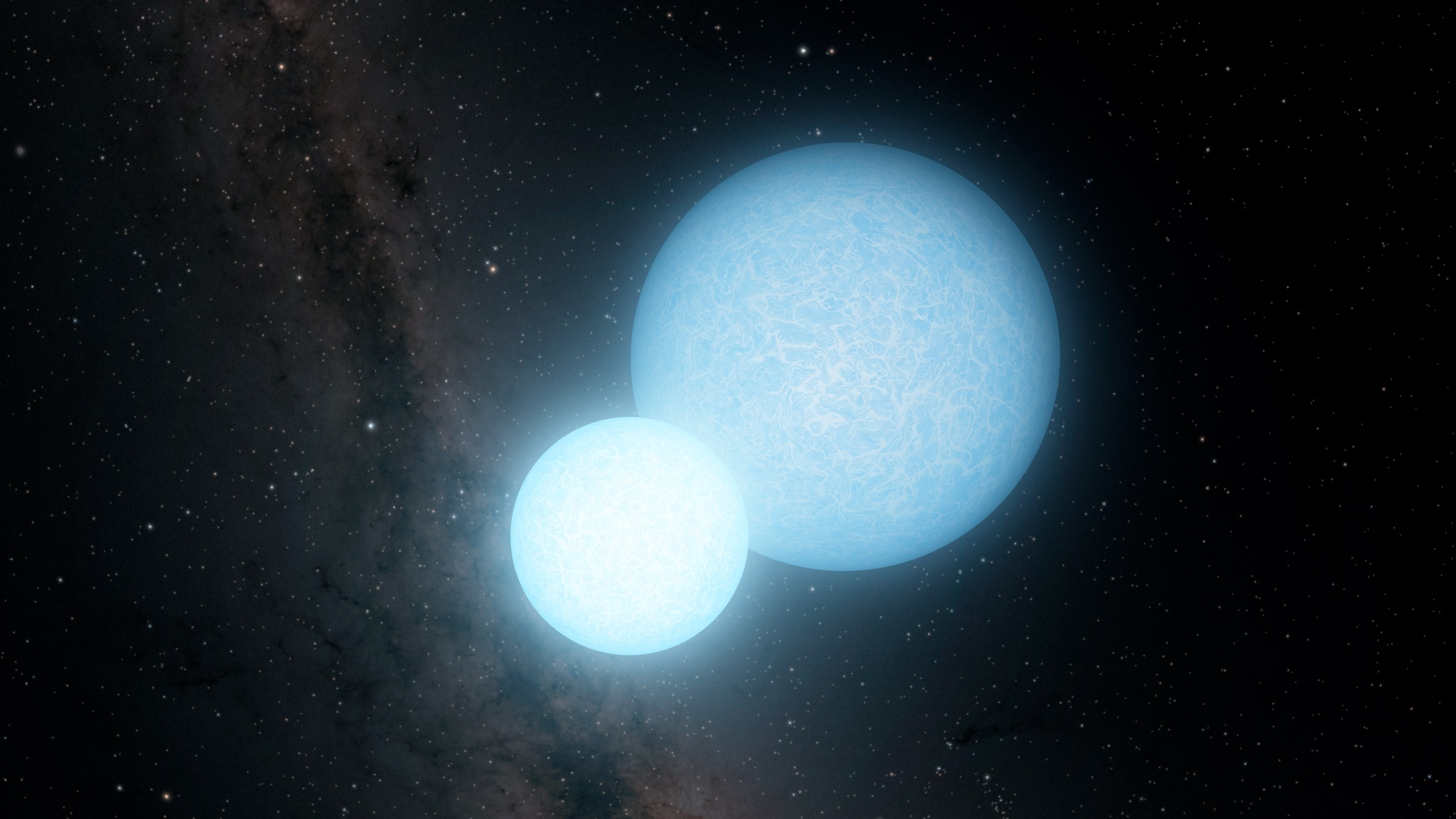

The two white dwarfs, a pair known as ZTF J1539+5027, orbit one another and are both roughly the size of Earth, though one is a bit smaller and brighter than the other. The pair appear to "blink" when the dimmer star passes in front of the brighter star, eclipsing it. This is the second fastest pair of orbiting white dwarfs ever observed (the fastest was observed with an orbital period of 5.4 minutes, according to Burdge) and the fastest binary system in which one object completely eclipses the other (from our point of view).

Related: How to Tell Star Types Apart (Infographic)

Scientists continue to debate over whether binary systems like this will eventually merge, with one of the dead stars consuming the other, or if they might remain with both bodies in orbit around one another, Burdge told Space.com. The gravitational waves that they emit might cause them to merge in about 200,000 years, he added.

But, in about 100,000 years, it's possible that the smaller star will start dumping matter onto the larger star, a process that could stabilize its orbit and prevent it from shrinking further, Burdge said.

And, as Burdge said in a separate statement, systems like this are rarely spotted, and more often scientists see binary systems where one star has mostly consumed its orbital partner.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But this binary system is unique in more ways than one. "It's a really weird binary and that's part of the reason we found it," Burdge told Space.com. As Burdge explained, the slightly smaller, brighter star is unusually hot, at about 50,000 Kelvin (about 90,000 degrees Fahrenheit, or 49,982 degrees Celsius), or 10 times hotter than the sun.

This extreme temperature makes the star brighter and its orbit deeper, which made it easier to spot in the ZTF data, according to Burdge, who also suggested that perhaps there are many other similar systems that are cooler, making them more difficult to spot. Improved sky-scanning technology with ZTF has also allowed for this observation, but "this particular system is really weird, which made it easy to pick out," Burdge said.

The pair is one of the only identified sources of gravitational waves that will be picked up by the future European space mission Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), which is scheduled to launch in 2034.

"Within a week of LISA turning on, it should pick up the gravitational waves from this system. LISA will find tens of thousands of binary systems in our galaxy like this one, but so far we only know of a few. And this binary-star system is one of the best characterized yet due to its eclipsing nature," co-author Tom Prince, the Ira S. Bowen Professor of Physics at Caltech and a senior research scientist at JPL, said in the same statement.

Scientists studying the pair of dead stars can will be able to discern their distance from Earth by studying the pair's gravitational waves, Burdge said. With LISA and the likely discovery of more pairs like these, scientists will have many more opportunities to study gravitational waves, which could help to solve some of the mysteries of the cosmos.

This study, titled "General relativistic orbital decay in a seven-minute-orbital-period eclipsing binary system," will appear in the July 25 issue of the journal Nature.

- Inside a Neutron Star (Infographic)

- Know Your Novas: Star Explosions Explained (Infographic)

- Alien Comets of Star Beta Pictoris Explained (Infographic)

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.