Wild idea: Tagalong spacecraft could watch a comet form

A few decades from now, humanity could get an up-close look at a comet blazing to life for the first time.

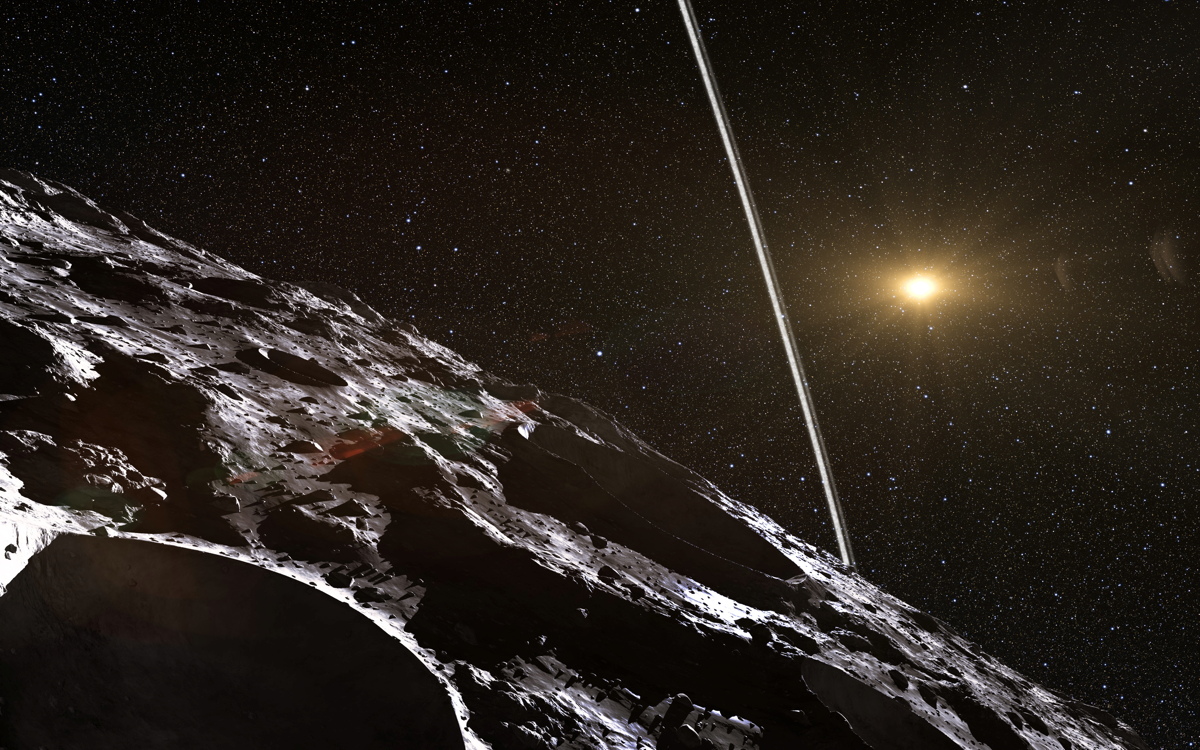

In a new study, researchers investigated the dynamics of the Centaur population, a group of icy rocks orbiting the sun near Jupiter and Saturn. The Centaurs are so named because they're hybrids of a sort, sharing some characteristics with both asteroids and comets.

Scientists believe that Centaurs were born in the giant-planet realm but have spent most of their lives in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of frigid bodies beyond Neptune's orbit. Gravitational interactions sent them out there long ago and also brought them back again relatively recently; Centaurs' orbits are unstable, so they likely haven't been in their current position for more than a few million years.

Related: Our solar system: A photo tour of the planets

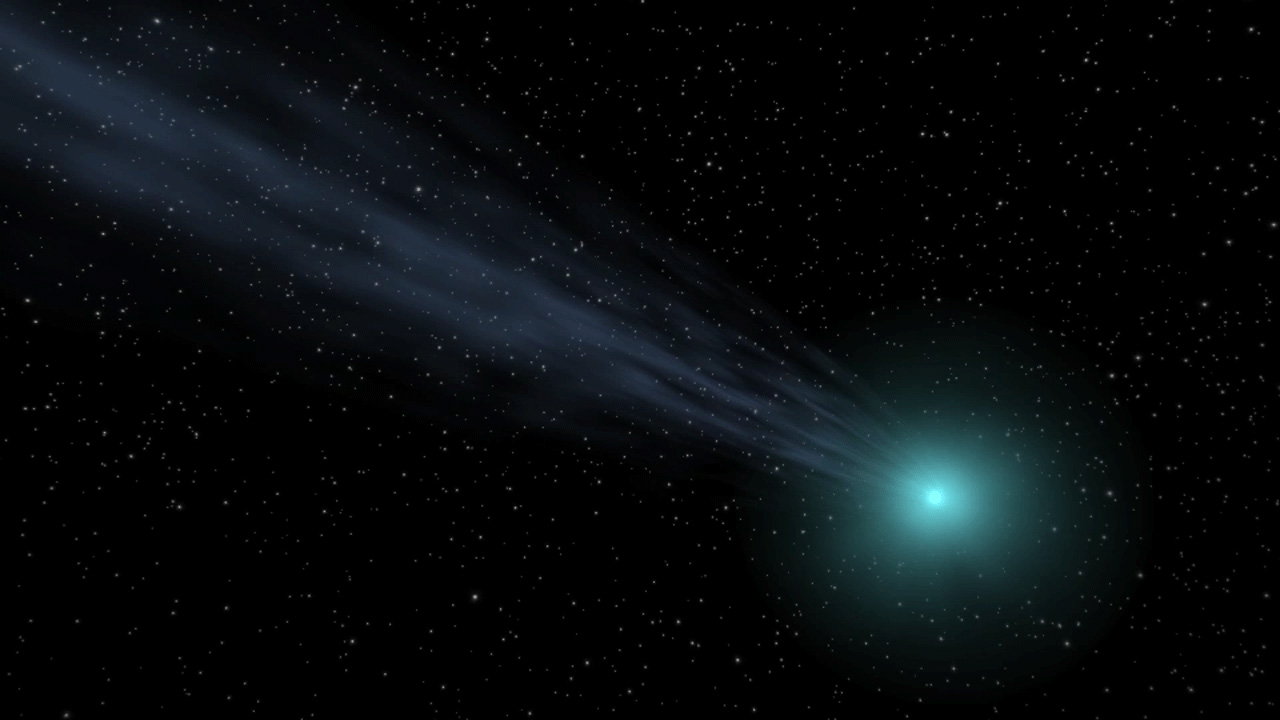

Some Centaurs end up getting another very consequential gravitational nudge — a push inward, toward the sun. These objects then become comets, sprouting fuzzy comas and long, beautiful tails as they near our star and heat up.

In the new study, scientists modeled how this transition from Centaur to comet comes about. They found that about half of the newly minted comets were set on their sunward course by interactions with the orbits of both Jupiter and Saturn. The other half got too close to Jupiter and were flung inward.

This latter process affords humanity an exciting opportunity, the research team determined: A spacecraft could linger in orbit around Jupiter, waiting for a Centaur to venture too close — and then follow the booted object on its new trajectory, watching as it heats up and turns into a comet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The data such a probe gathered would provide a rare glimpse into the solar system's early days, study team members said.

"These objects are very old, containing ice from the early days of the solar system that has never been melted," study lead author Darryl Seligman, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago, said in a statement.

"You could figure out where typical comet ices turn on, and also what the detailed internal structure of [a] comet is, which you have very little hope of figuring out from ground-based telescopes," he added. "Charting all of this would help you understand the dynamics of the solar system, which is important for things like understanding how to form Earth-like planets in solar systems."

Related: The greatest comet close encounters of all time

Seligman and his colleagues even identified a possible target: a Centaur called P/2019 LD2, which will veer close to Jupiter in 2063. There's a greater than 98% chance that this encounter will kick the object sunward, turning it into a comet, the team determined. Their calculations further show that a probe lurking near Jupiter could catch up with the object and fly along with it, as long as the spacecraft began heading for a rendezvous point in 2061.

And astronomers may identify other Centaurs that could be visited before 2063, the researchers said. A number of such targets may be discovered by the powerful Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is scheduled to come online in Chile in early 2023, they added.

“We have records of comets dating back thousands of years; how cool would it be to see how that happens up close?" Seligman said.

A number of other researchers share this fascination with the Centaurs, none of which have been visited by a spacecraft to date. For example, two separate teams proposed Centaur missions for launch in the 2020s via NASA's Discovery program, which develops low-cost robotic exploration efforts. However, the agency did not pick either one, instead going with two Venus missions.

The study by Seligman and his team has been accepted for publication by The Planetary Science Journal. You can read a preprint of it for free at arXiv.org.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.