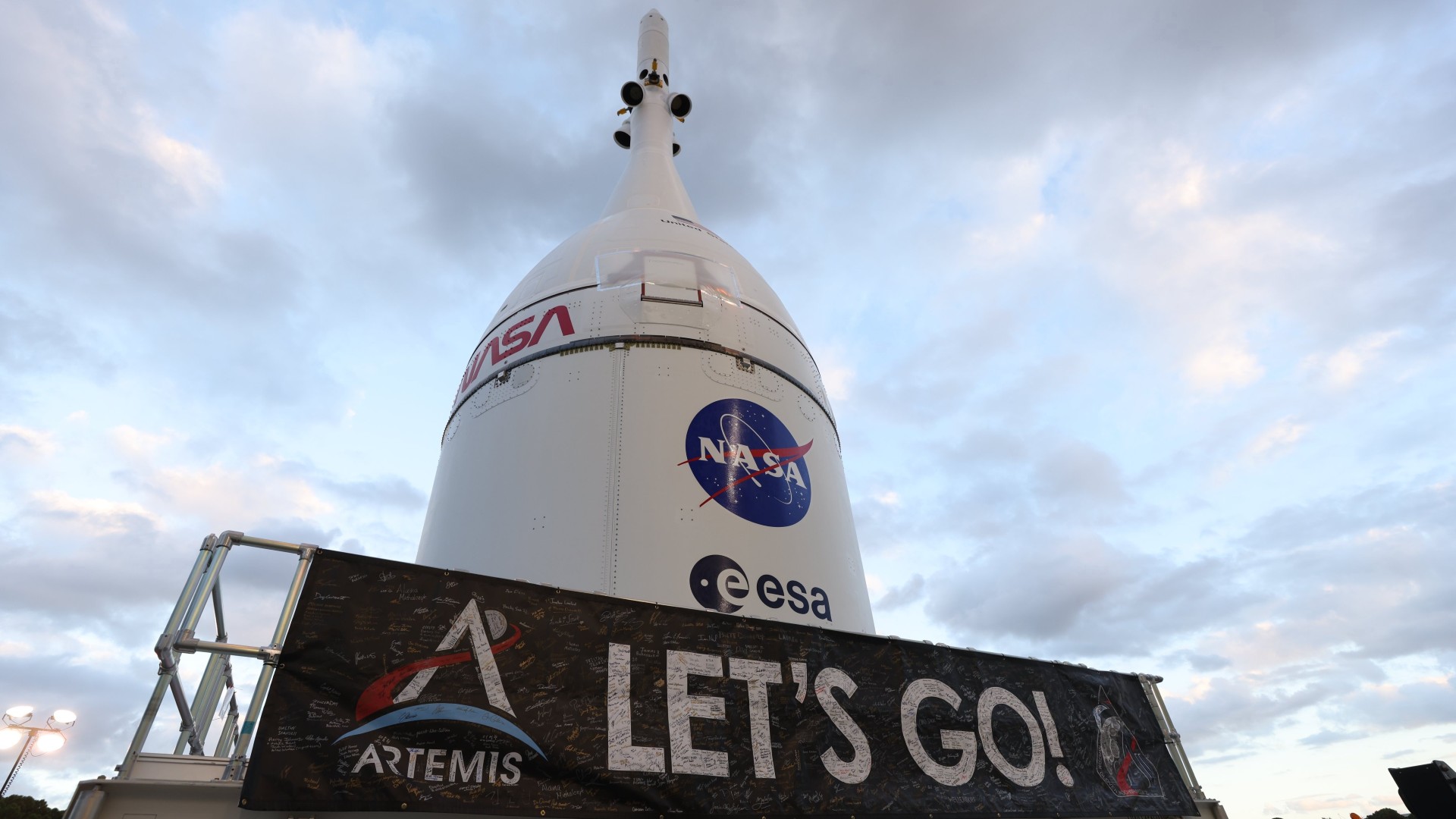

'It's so complicated:' Boeing Starliner teams diagnosing helium leak ahead of June 1 astronaut launch

"We really just needed to work through it as a team."

Starliner is still set to fly on its historic first flight with astronauts on June 1, but that could change as the team works through "complicated" issues following a small helium leak.

NASA and Boeing officials emphasized they are carefully weighing the decision to launch Starliner's first test mission with astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). The approximately one-week mission is known as Crew Flight Test (CFT) and includes NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, both former U.S. Navy test pilots.

"It's so complicated. There's so many things going on. We really just needed to work through it as a team," Ken Bowersox, associate administrator for NASA's Space Operations Mission Directorate and a former astronaut, told reporters in a teleconference Friday (May 24). He added that addressing the issues have taken a lot of time, which is part of why few updates have been forthcoming from the team in recent weeks.

Related: 2 astronaut taxis: Why NASA wants both Boeing's Starliner and SpaceX's Dragon

A delta flight readiness review on Wednesday (May 29) will take place to review the leak and the changes in which the team may do a deorbit burn, if necessary. This is a bit different from the standard flight readiness review as the interim human certification document for CFT changed because of this new situation, he added. NASA will then hold another call with reporters on Thursday (May 30), agency officials said.

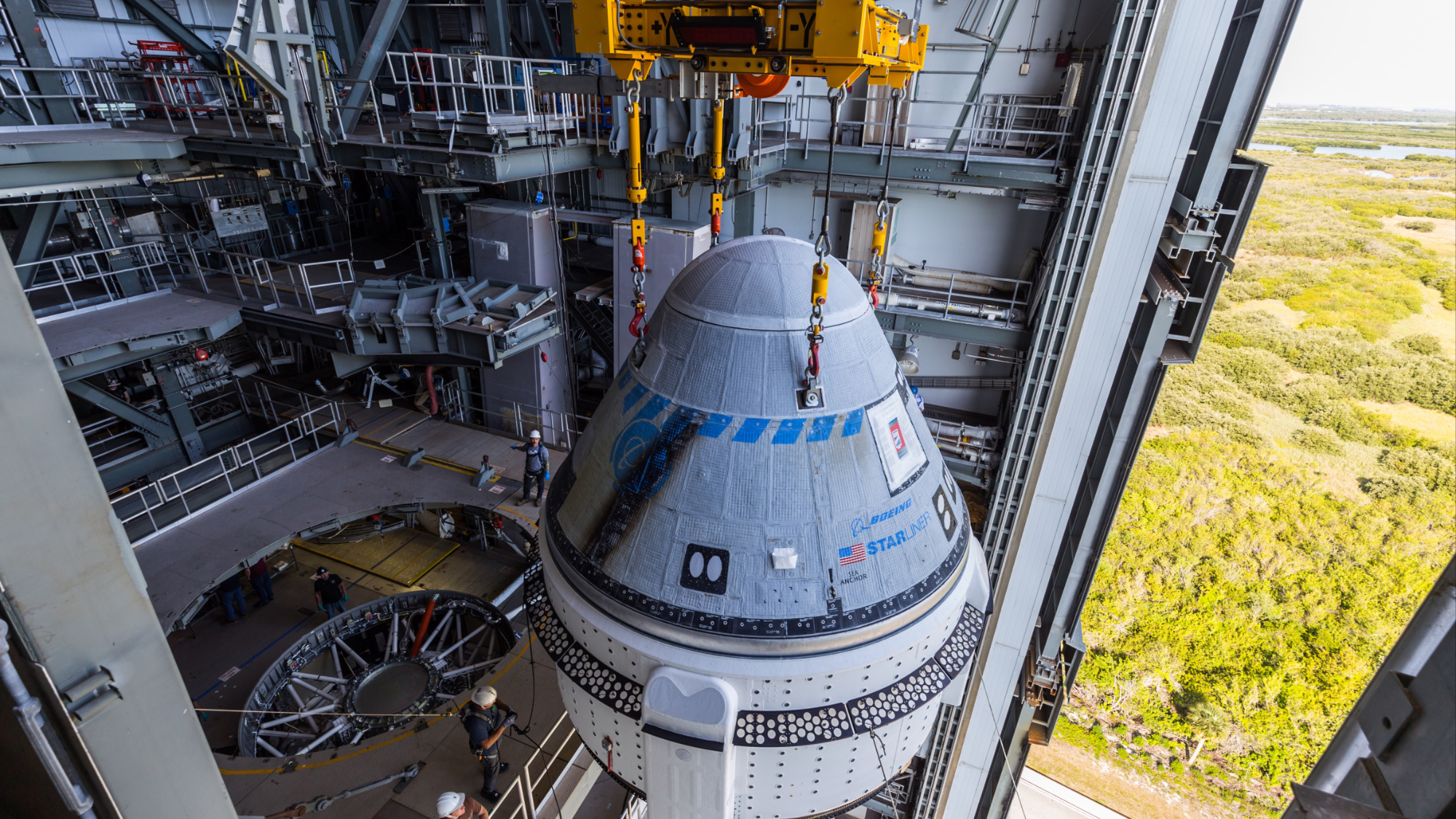

Starliner was delayed from its May 6 launch attempt, only two hours before liftoff, due to an oxygen relief valve issue on the Atlas V rocket set to launch the astronauts from the coastal Cape Canaveral Space Force Station near Orlando, Florida. United Launch Alliance (ULA), the company that makes the rocket, elected to replace the "buzzing" valve, which was opening and closing rapidly.

That valve swap went according to plan by May 12, but another issue — a helium leak in Starliner — was found after the launch scrub. Examining what happened, and how to solve it, required pushing back the launch dates several times, most recently to no earlier than June 1.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During the teleconference, NASA and Boeing officials said if the Starliner leak had happened in space, they would have found ways to deal with it there; they emphasized the leak was tiny and that hardware can fail unexpectedly even on fully certified spacecraft systems.

"There's no human-rated vehicle that doesn't experience this kind of anomaly," said Boeing's Mark Nappi, vice president and program manager of the company's commercial crew program. (In other parts of the press conference, examples were given from SpaceX's Crew Dragon, also used for commercial crew flights, and the retired space shuttle program that used to handle NASA launches.)

Related: 2 astronaut taxis: Why NASA wants both Boeing's Starliner and SpaceX's Dragon

Helium, as a non-inert gas, is not an immediate risk to a launch. But as it is in a part of the Starliner propulsion system, it could affect the pressurization for small maneuvers in orbit. Aside from studying that leak, NASA and Boeing have been working to learn how the helium system could potentially affect Starliner's return to Earth.

The leak is located in one Aerojet Rocketdyne reaction control system (RCS) thruster that is located in a single "doghouse," one of four such assemblies around the outside of Starliner's service module. It is in a manifold that is "used to open and close valves on each of the thrusters," said NASA's Steve Stich, program manager for the agency's commercial crew program.

He said the situation caused Starliner's team to pay more attention to the manifolds; while NASA says the pre-checks were robust, "maybe in a perfect timeframe. We might have identified this earlier." But that is precisely the role of a test flight, to identify such issues, he noted.

NASA, Aerojet Rocketdyne and Boeing are evaluating about five solutions to prevent the leak from reoccurring on future missions. Even then, Stich added, "Helium is a tiny molecule. It tends to leak."

The leak began at 7 pounds per square inch (psi) and has increased to between 50 psi and 70 psi, coming from a less-than-button-sized area in the Starliner spacecraft that is less than 10 sheets of paper thick. (Engineers could not safely open up the leaky spot while Starliner was stacked on its Atlas V in ULA's Vertical Integration Facility, so they have been analyzing the leak using software tools instead.)

The leak is from a rubber seal that is in between two metal parts of a flange, which "keeps that interface tight so that the helium can pass through there," Stich said.

The other 27 thrusters in the RCS are not leaking at all, he emphasized, and analysis determined Starliner could handle up to four more thruster leaks — or a leak of up to 100 times higher in this one zone. Additionally, engineers tested the system through several pressure changes and the leak was "relatively stable" through those changes, he said.

Stich said studying the helium leak brought to light a "design vulnerability" in the propulsion system. There are three certified techniques in which Starliner could come back home: Eight RCS thrusters, two orbital maneuvering and attitude control (OMAC) thrusters, or four OMAC thrusters.

But under "the right circumstances of failures," meaning the loss of two manifolds of thrusters in adjacent doghouses, they could lose the ability to fire eight RCS jets at once and thus, also lose a form of backup.

"So we wanted to take extra precaution to understand, what could we do if we lost our thrusters? We've worked with the vendor of the thruster [Aerojet Rocketdyne], Boeing and our NASA team to come up with a redundant method to do with your burn: To break it up into two burns, about 10 minutes each [and] 80 minutes apart, to come up with a four-RCS-thruster deorbit burn and to regain the capability of the original system.

"And that took a little time for our team to go work through," he continued, saying it involved NASA teams in guidance and navigation, structures and propulsion alongside Aerojet Rocketdyne and Boeing teams. "So we have that restored that redundancy for the backup capability in a very remote set of failures for the deorbit burn."

The crew successfully tested out this scenario in a simulator recently, likely one of the high-fidelity ones at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston (where they remain in quarantine.) This change in the redundancy, however, is one of the primary drivers behind the upcoming delta flight readiness review on May 29 to review the human certification for Starliner, Stich said. The team also wanted to take the time to examine the helium leak and all fixes, after resting this Memorial Day weekend.

June 1 is not a lock, as the work is still on progress, but several backup dates exist in the near term: June 2, June 5 and June 6 are near-term opportunities for Starliner to launch, and there are other chances in the early summer as well.

Starliner would remain stable long beyond then, said Nappi. But the Atlas V rocket has some parts that would expire in June and July, said ULA's Gary Wentz, who is vice president of government and commercial programs. Other launches may also have to shift around if the delay persists.

CFT is only allowed to dock at a single port of the Harmony module of the ISS, but "we're pretty flexible all through the summer" if Starliner needs to hold, ISS program manager Dana Weigel told Space.com during the press conference.

As is true of all launches, CFT would not be scheduled to arrive at the ISS on docking, undocking or spacewalking days on the ISS, but that port could remain empty until at least crew rotation activities in August, she said. Earlier that month, a Northrop Grumman Cygnus will berth in a separate port of the ISS, and if the CFT astronauts are on station at that time they may help with unloading activities if time permits.

Williams and Wilmore will return to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where quarantine quarters are a few miles from the launch pad, a few days before launch. The current June 1 launch would see them come back on May 28.

The crew has been in quarantine for about a month, waiting through the delays, but are "in good spirits," Bowersox said. Wilmore and Williams remotely attended meetings and among other comments have urged the team to pace themselves, he said. (As military astronauts and former U.S. Navy test pilots, the CFT crew are also used to both long deployments as well as working on developmental programs like Starliner, where schedule changes like this are common.)

Boeing is the other vendor for commercial crew aside from SpaceX, after they were selected for astronaut taxis in 2014. The initial expectation for crewed flights was 2017, but technical and funding problems caused delays. SpaceX has sent a dozen missions to the ISS since 2020, borrowing from its cargo Dragon design (first used in space in 2012) to inform the design of Crew Dragon.

Starliner, a new spacecraft, has yet to carry astronauts aloft. An uncrewed test flight in 2019 did not go forward as planned; the spacecraft never reached the ISS after a software glitch stuck it in the wrong orbit. The next attempt in 2022 (delayed by the pandemic, and after dozens of fixes were implemented), made it there with no issue.

CFT delayed again in 2023 after new issues were found with the parachutes (which carried less load than expected) and wiring (covered in flammable tape). Those problems are behind the team, Boeing and NASA have stressed repeatedly in recent weeks.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.