Bacteria could make super-efficient rocket fuel

Some of Earth's tiniest inhabitants could help humanity explore the final frontier.

Some of Earth's tiniest inhabitants could help humanity explore the final frontier.

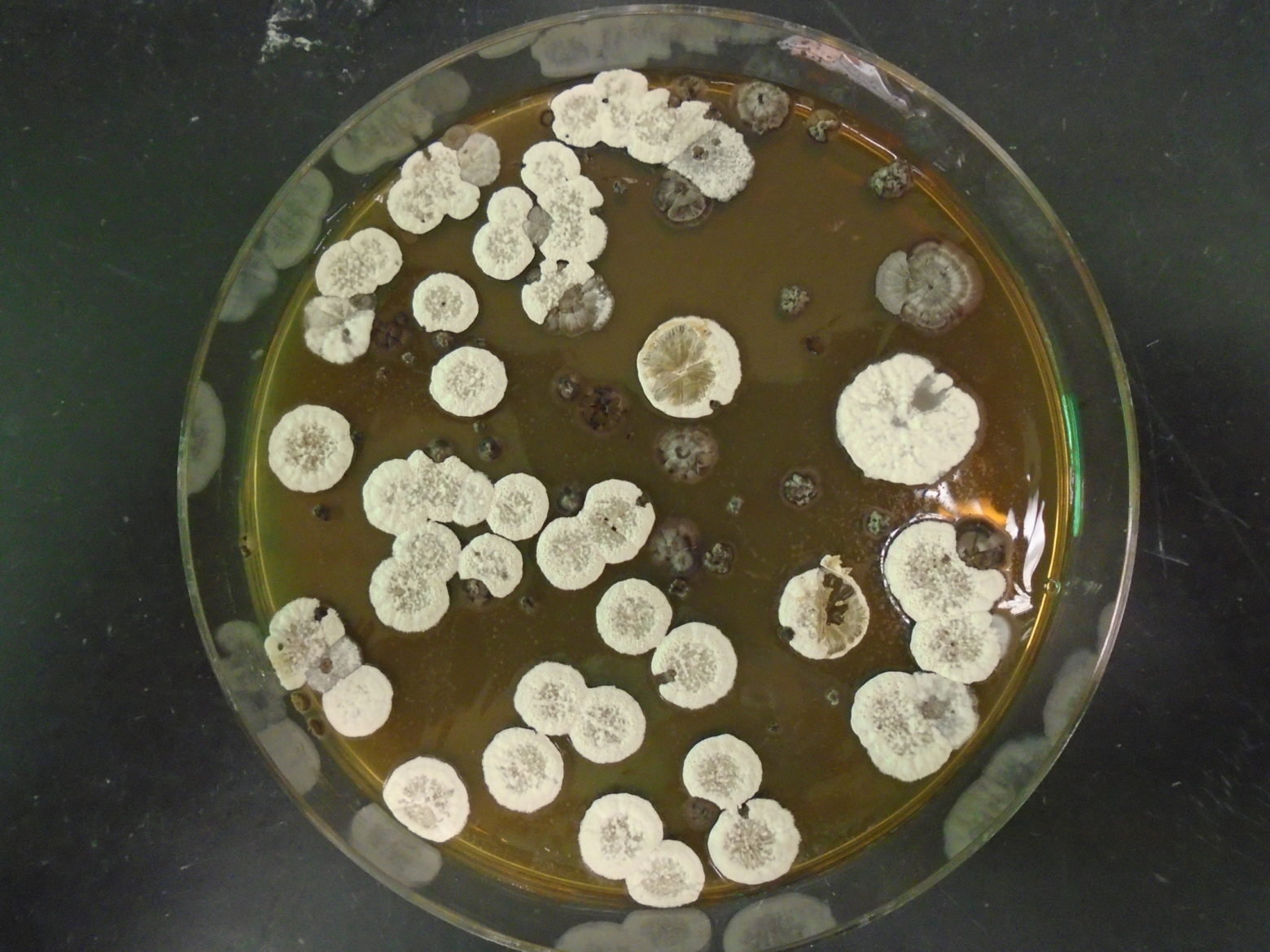

A newly developed biofuel — based on an antifungal molecule made by Streptomyces bacteria — could be used in future rocket launches, researchers say.

The potential eco-friendly solution to rockets dumping carbon into Earth's atmosphere may also have significantly more energy density than rocket fuels used today, project team members said in a press release.

"As these fuels would be produced from bacteria fed with plant matter ... burning them in engines will significantly reduce the amount of added greenhouse gas relative to any fuel generated from petroleum," project leader Jay Keasling, CEO of the Department of Energy’s Joint BioEnergy Institute, said in a press release.

While the project is very much in its early stages, researchers say the unique chemistry of the fuel candidate molecules show incredible promise in hefting future boosters into space.

Related: The history of rockets

Many rocket engines today burn liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen as propellants. But even this relatively "green" combination may be paired with supplemental boosters with potentially nastier variants of fuel to get a rocket off the ground.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

With a growing number of studies focusing on rocket launches and their impact on Earth's atmosphere, some environmentalists say spaceflight needs new solutions — especially as the number of launches increases. (Some other exploration advocates, on the other hand, point out that space has a relatively small amount of carbon footprint compared with other industries.)

Nevertheless, the bacteria-driven biofuel researchers say their fuel candidate is also extremely energetic, potentially boosting rockets beyond their current capabilities. The key molecules are called POP-FAMEs, short for "polycylcopropanated fatty acid methyl esters."

The structure of these molecules include triangle-shaped, triple-carbon rings that strain carbon-carbon bonds into an extreme 60-degree angle. This strain produces high potential combustion energy, and the unusual structure also allows for fuel molecules to compress into a relatively small volume, the researchers said.

That combination of characteristics could work out great for spaceflight, proponents say, as engineers are always trying to cut down on launch mass to save on fuel and cost.

The research team's work focuses on two known examples of organic compounds with three-carbon rings, both generated by Streptomyces bacteria. While this lifeform is very difficult to grow in a lab, a species in the genus called S. roseoverticillatus was genetically analyzed, and, in 1990, scientists announced the discovery of a natural product called jawsamycin.

This "toothy" molecule, which features five cyclopropane rings, inspired Keasling's team to examine the genomes of related Streptomyces species for potential rocket fuel applications. They subsequently uncovered the "necessary ingredients" for POP-FAMEs in another strain, S. albireticuli.

Like many of its relatives, S. albireticuli proved to be a lab diva, refusing at first to create enough POP-FAMEs for researchers to analyze. Eventually, however, the scientists hit upon a "tame" relative that allowed for experimentation, but only after the team copied over their rearranged gene cluster into the variant.

"The resulting fatty acids contain up to seven cyclopropane rings chained on a carbon backbone, earning them the name fuelimycins," the press release states. "In a process similar to biodiesel production, these molecules require only one additional chemical processing step before they can serve as a fuel."

The next stage in rocket fuel development would be to produce enough molecules for field tests, which generally require at least 22 pounds (10 kilograms). The researchers are not nearly there yet, which is why the research remains tentative at this time.

However, simulation data to date suggests that POP-FAMEs may produce energy density values of 50 megajoules per liter after chemical processing. That's a notable increase over gasoline (32 megajoules per liter) and RP-1, a kerosene-based rocket fuel that boasts about 35 megajoules per liter.

POP-FAMEs are notably close in structure to an experimental petroleum-based rocket fuel, showing that these bacteria-produced molecules might be a feasible alternative. The experimental fuel, called Syntin, was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s. While Syntin was used in Soyuz rocket launches in the 1970s and 1980s, high costs, explosive potential and toxicity eventually led to the Soviet Union abandoning the fuel.

The POP-FAME team now is working on increasing the production efficiency of the bacteria for combustion testing, and to create molecules of different lengths to target applications for solid fuel, jet fuel and diesel alternatives. Further in the future, scientists hope to use plant waste food as a source to make the fuel generation process carbon-neutral.

A study based on the research was published in the journal Joule on Thursday (June 30).

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.