Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

At one time or another, most of us have probably used a Swiss Army Knife. An excellent everyday tool, it's really just a glorified pocket or penknife; a tool incorporating several blades and other appliances such as scissors and screwdrivers.

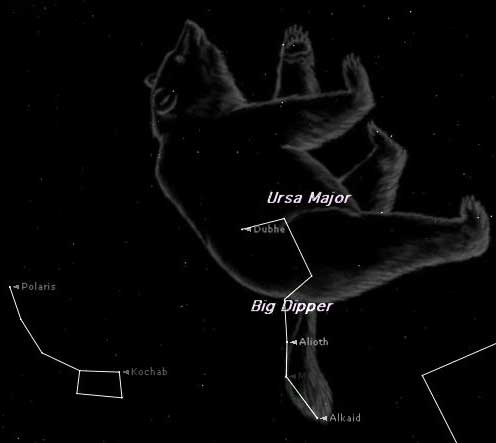

And ascending the northeast sky on February evenings is what we might call the "Swiss Army Knife of the sky": the Big Dipper. It is not an official constellation in itself; rather, it's a prominent grouping of stars (called an asterism) that forms a different type of star pattern within a recognized constellation — in this case, Ursa Major, the great bear.

But the Dipper is more than just a bright and familiar star pattern. It's a compass, a clock, a calendar and a ruler all rolled into one!

Related: A star in the Big Dipper is an alien invader

A compass

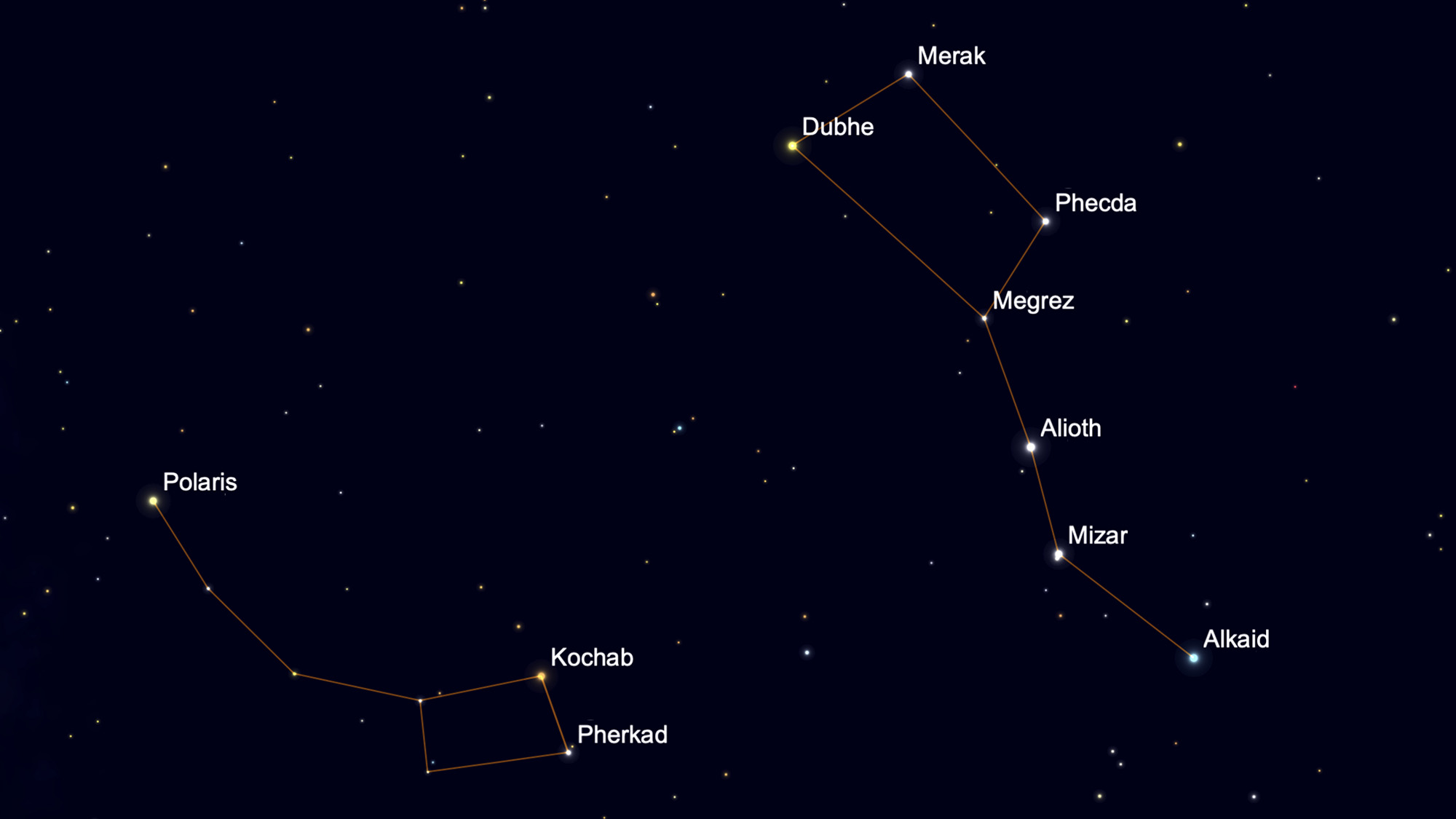

As a compass, we need only go to the two stars at the end of the bowl of the Dipper — Dubhe and Merak — known as the "pointer stars," which serve as a stellar compass needle, pointing directly toward Polaris, the North Star.

An imaginary line drawn and extended from Merak through Dubhe (at the top of the bowl) and extended about five times the distance between the two brings us unerringly to Polaris. Once you find Polaris, you're facing due north. Behind you is south; to your left is west and to your right is east.

A clock

We can also use the Dipper as a celestial clock. In his book "Star Lore of All Ages" (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1911), William Tyler Olcott, the early 20th century American lawyer and amateur astronomer, wrote:

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The entire figure of the Great Bear circles about the pole once in twenty-four hours. This is, of course, an apparent motion due to the rotation of the Earth. A line connecting the 'pointer stars' with Polaris may be regarded as the hour hand of a clock. With a little practice, the time of night can be ascertained to an approximate degree by the position of this stellar hour hand."

The only thing that makes our sky clock different from the ones we have in our home (or around your wrist) is that the Big Dipper moves around Earth's geographic North Pole in a counterclockwise direction. What is required to learn how to tell the time using the Big Dipper, is a period of frequent comparison — repeated anew for each season — of the position of the line running from Polaris through the pointer stars with the local time on your clock.

The length of time required to do these observations depends on how assiduous an observer you are. Through a process of mental association between the celestial and mechanical hour hands, it becomes possible to estimate the time directly from the sky alone. With practice, this can be carried to a surprising degree of accuracy. I know some people who are able to tell what time it is using this methodology within just a few minutes of what the actual time happens to be! If you go out several nights a week, and note afterwards what the time is when you go back inside, after a while you won't need to check the clock or your watch — you'll pretty much know what hour of the night it is.

A calendar

In addition to its role as a sort of cosmic chronometer, the Big Dipper can also serve as a calendar. From the relative position of the Big Dipper with respect to Polaris, the season of the year — and eventually with practice, even the month — can be determined by looking at the sky.

During the hours just after darkness falls in the spring, we can find the asterism soaring high above the northern horizon and stretching to the point almost directly overhead (the zenith). But by summer it has turned counterclockwise by 90 degrees; the bowl now points downward and it lies to the west of the pole during the early evening hours.

By fall evenings, the Big Dipper is far beneath Polaris and skims the northern horizon. This position in the sky is appropriate in a way, as bears are going into hibernation at this time of year, and as we mentioned earlier, the Big Dipper is part of the big bear constellation, which is now partially hidden below the northern horizon. And now, during the winter we find it ascending the sky once again, standing on its handle around 9 p.m. local time in the Northeast.

A yardstick

Finally, another valued and fascinating use of the Big Dipper is that we can use it as a convenient astronomical yardstick by which we can measure angular sizes and distances in the sky. Sky angles ranging from 5 to 25 degrees in extent can be determined using the stars of the Big Dipper. While other well-known asterisms, such as the Great Square of Pegasus in autumn, or constellations such as Orion in winter , can serve this same function, the Big Dipper is visible at all seasons and therefore is the most handy sky ruler of them all.

The gap between the pointer stars measures 5.5 degrees. Since the moon measures about one-half degree in apparent diameter on average, we could fit 11 full moons in the gap between Dubhe and Merak.

The next time you see the Big Dipper in the sky, study the distance between the two pointer stars and judge for yourself how many moons you might fit between them. It may look like only four or five can fit — but 11? This, along with the seemingly "bloated" appearance of a rising or setting moon, is one of the best optical illusions in the sky, but yes ... 11 full moons would indeed fit between the two pointer stars.

Getting back to our celestial measuring stick, the distance between the two stars across the bottom of the bowl (Merak and Phecda) is 7 degrees, while the two stars along the top (Dubhe and Megrez) are 10 degrees apart. From Dubhe to Alkaid (the star at the end of the handle) measures 25 degrees, and from Dubhe to Polaris stretches 28 degrees.

Some examples of the uses to which we might put this starry ruler include estimating the path length of a bright meteor or fireball streaking across the sky, or determining the length of the tail of a bright comet. As a further instance, suppose we read that a planet is to be visible on a certain evening 7 degrees north of the moon. A glance at the Big Dipper will provide the eye with an immediate "feel" for this distance.

That close?

For smaller night-sky measurements, check out the middle star in the handle of the Big Dipper. That's Mizar, and located just to its upper left is a smaller, dimmer star known as Alcor. If you have normal eyesight, you should be able to separate both stars without any optical aid. These two stars are separated by 12 arc minutes, or 0.2 degrees. That's less than half of the apparent diameter of the moon.

Keep that in the back of your mind, because later this year, on Dec. 21, Jupiter and Saturn are going to have an exceedingly close encounter with each other. In their closest approach since 1623, the planets will be separated by 6 arc minutes, or just one-half the distance of Mizar to Alcor. On that evening, you'll be able to fit both Jupiter and its four Galilean moons and Saturn and its famous rings in the same field of view of a high-power telescope.

Mark your calendars.

- The brightest planets in February's night sky: How to see them (and when)

- Big Dipper stars shine over stargazer in amazing photo

- A skywatcher shows you where to find the North Star (photo)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.