Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

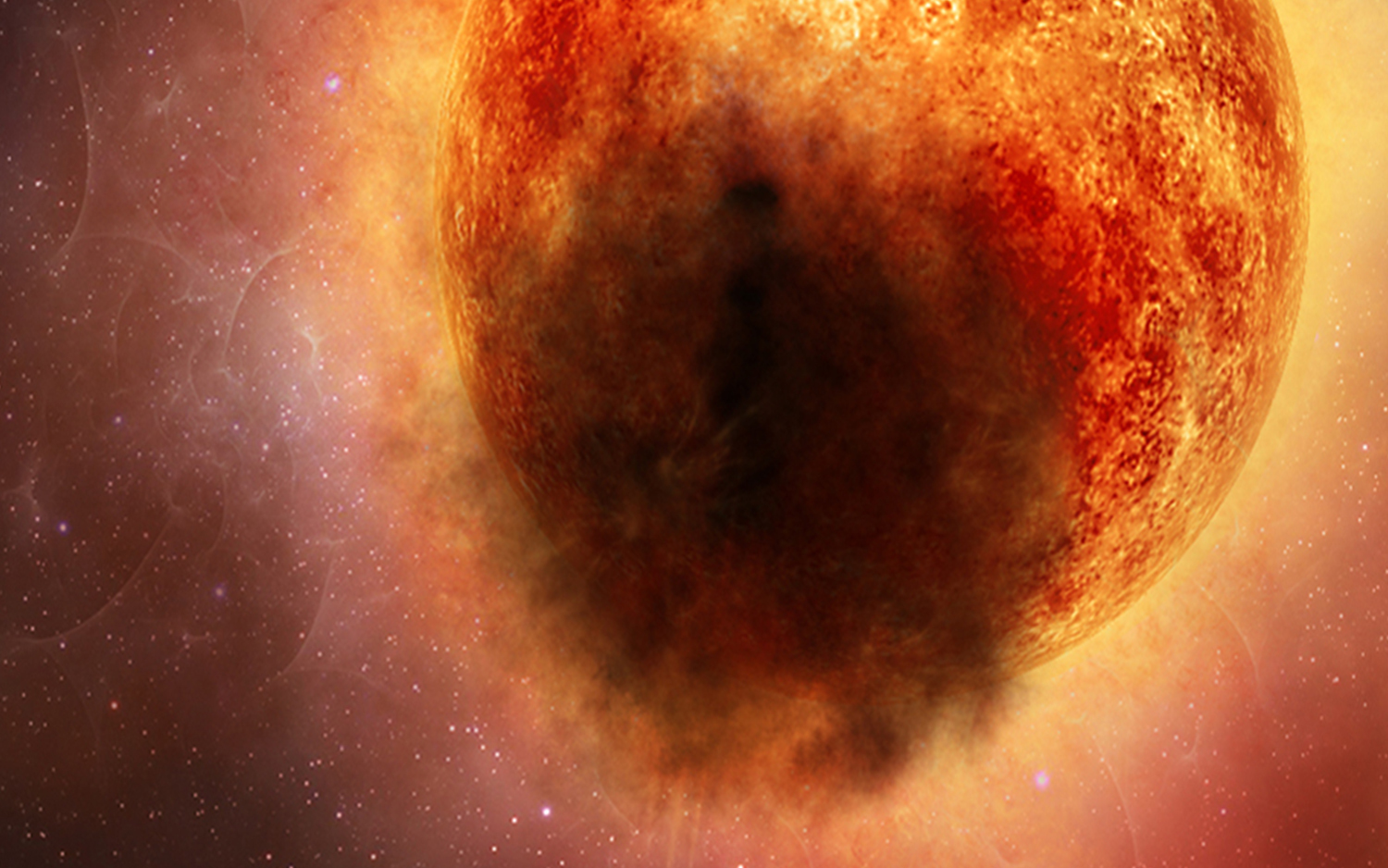

Betelgeuse's odd recent dimming was caused by a huge cloud of material that the supergiant star blasted into space, a new study suggests.

The bright star Betelgeuse, which forms the shoulder of the constellation Orion (The Hunter), is about 11 times more massive than the sun but 900 times more voluminous. That bloated condition shows that Betelgeuse is near death, which will come in the form of a violent supernova explosion.

In the fall of 2019, Betelgeuse began dimming significantly, losing about two-thirds of its brightness by February. This dramatic dip spurred speculation that the star's demise may have been imminent — perhaps just weeks away. (From our perspective, anyway; Betelgeuse lies about 500 light-years from Earth, so everything we're seeing with the star today happened centuries ago.)

Article continues belowRelated: The brightest stars in the sky: A starry countdown

But the dramatic sky show didn't happen: Betelgeuse powered through the dimming episode and returned to its normal brightness by May of this year. The recovery sparked a new round of speculation, this time about the dimming's cause. Some scientists attributed the doldrums to a light-blocking dust cloud, for example, whereas others said big starspots on Betelgeuse's surface were likely to blame.

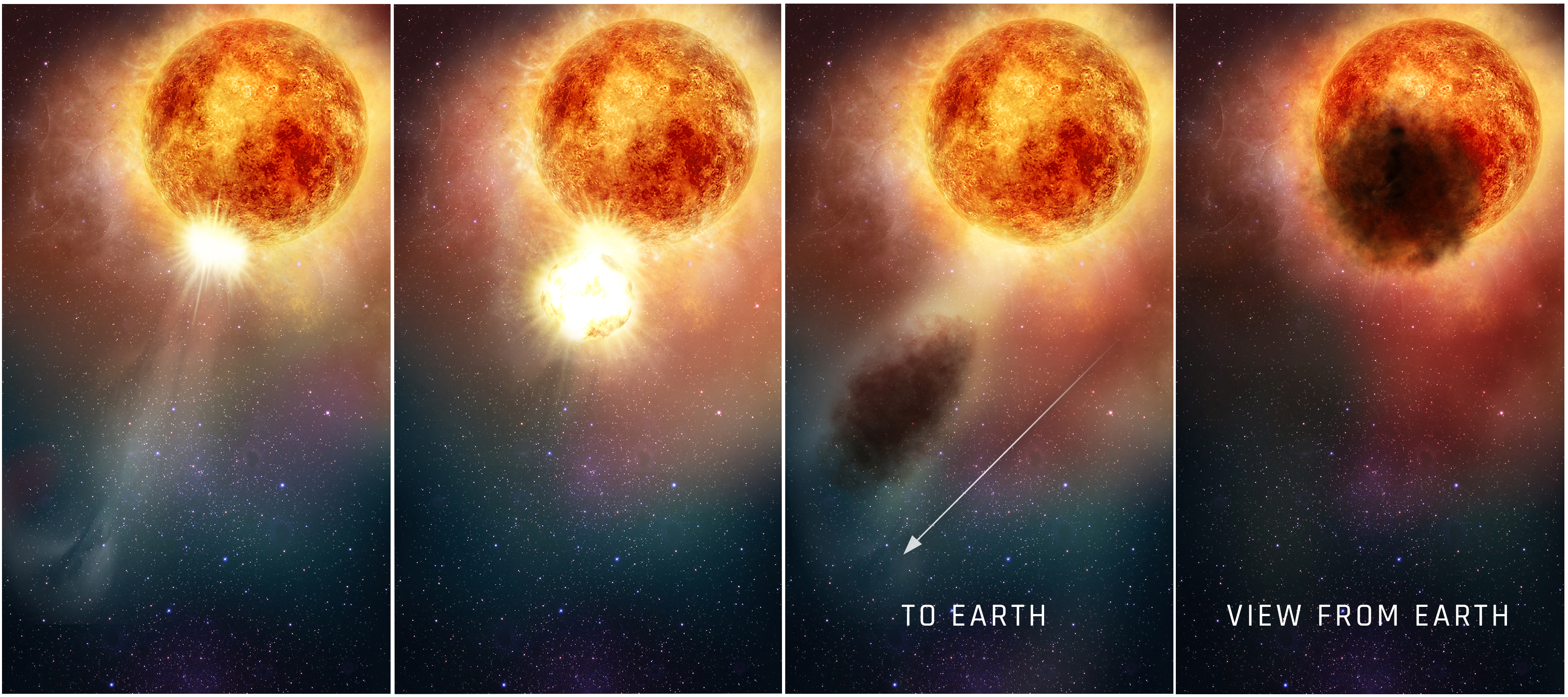

A new study bolsters the dust hypothesis, but adds a twist — Betelgeuse itself apparently coughed up the cloud.

The researchers studied the star in 2019 and 2020 using NASA's iconic Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble's observations from September through November 2019 revealed huge amounts of material moving from Betelgeuse's surface to its outer atmosphere at tremendous speeds — about 200,000 mph (320,000 km/h).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During this three-month-long outburst, Betelgeuse lost about twice as much material to space from its southern hemisphere as it normally does, study team members said. (Betelgeuse's background shedding rate is significant, by the way — about 30 million times that of our sun.)

This superhot plasma, or electrically charged gas, cooled considerably after traveling millions of miles from Betelgeuse, condensing into dust grains and forming a light-blocking cloud, the scientists suggested in the new study, which was published online today (Aug. 13) in The Astrophysical Journal.

"This material was two to four times more luminous than the star's normal brightness," lead author Andrea Dupree, associate director of the Center for Astrophysics run by Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said in a statement.

"And then, about a month later, the south part of Betelgeuse dimmed conspicuously as the star grew fainter," Dupree said. "We think it is possible that a dark cloud resulted from the outflow that Hubble detected."

Additional Hubble observations backed up this interpretation. Ultraviolet light data showed that Betelgeuse's outer atmosphere had returned to normal by February 2020, even though the dimming in visible wavelengths continued.

It's unclear what caused the fall 2019 outburst. But Dupree and study co-author Klaus Strassmeier, of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in Germany, think it was likely abetted by Betelgeuse's regular pulsations.

The supergiant star expands and contracts on a 420-Earth-day cycle. Strassmeier measured the velocity of gas on Betelgeuse's surface using an automated telescope at the Leibniz Institute and found that the outburst occurred during the star's expansion phase.

Dupree plans to continue studying Betelgeuse with Hubble, and other astronomers will doubtless keep close tabs on the star as well. The supergiant is interesting enough in its current state, and observations of it would take on even more importance if Betelgeuse did go boom in the near future.

"No one knows what a star does right before it goes supernova, because it's never been observed," Dupree said. "Astronomers have sampled stars maybe a year ahead of them going supernova, but not within days or weeks before it happened. But the chance of the star going supernova anytime soon is pretty small."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.