Astronomers want to get in on NASA's push to the moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA wants to go to the moon, and astrophysicists want their instruments to ride along, too.

The details are still in flux, as scientists are figuring out what makes the most sense given the scientific and logistical constraints of the moon. But they're confident that NASA's current priorities at the moon offer benefits that would support their goals. The agency's priorities are embodied by the Artemis program, which aims to land humans on the moon in 2024 in a sustainable, long-term way that offers a future for science as well as exploration.

"Heavy launch capability, astronauts, serviceability, in-space assembly — all of those things are things that we care deeply about," Heidi Hammel, a planetary astronomer at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy said during the Lunar Surface Science Virtual Workshop held on May 28. "And they are a core part of the return to the moon initiative."

Related: NASA sees inspiration parallels between Apollo and Artemis moonshots

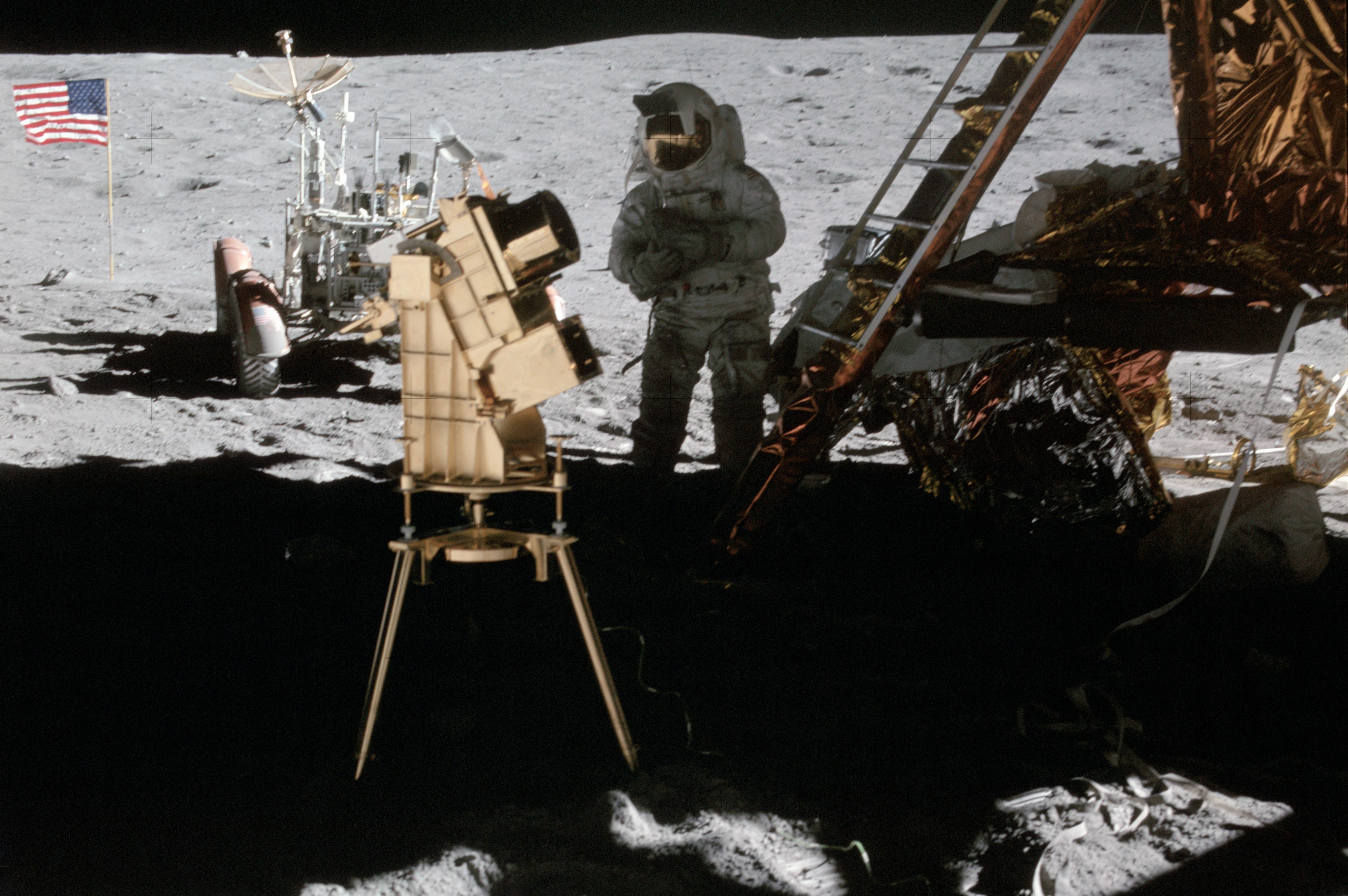

A few telescopes have already operated on the moon. NASA's Apollo 16 mission in 1972 carried an ultraviolet telescope that astronaut John Young used to image nebulas, stars and Earth's atmosphere. China's Chang'e-3 mission, which landed on the moon in 2013, also carried an ultraviolet telescope.

But the moon is generally new territory for telescopes, Hammel said, and the details of how astrophysicists might tap into the Artemis program remain to be determined. One important distinction may be between telescopes on the moon and telescopes at the moon. That's because even terrestrial dust is a problem for delicate astronomy equipment — and lunar dust is a whole lot more aggravating than its Earthly counterpart.

That said, it's not impossible to picture telescopes thriving on the lunar surface, Hammel said. She pointed to a volcanic mountain at the heart of Hawaii Island, Maunakea. Today, it's known for the dozen astronomy facilities perched on the mountain's summit, where the atmosphere is still and observing conditions are favorable. But in the 1960s, it was a key training site for Apollo-era astronauts practicing moonwalks and geology.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Maunakea was a proving ground for [the] lunar exploration program," Hammel said. "If we've learned nothing over the past 50 years … we have learned how to build telescopes in that kind of an environment." Those lessons, she said, may be applicable for any instruments that do need to be placed on the lunar surface.

Besides, astronomers have learned a lot about launching telescopes into space since the days of that first lunar telescope. Ground-based and space-based telescopes alike have improved exponentially. Consider the power of the Hubble Space Telescope, which, as future lunar-orbiting telescopes could do, has relied on visits from astronauts to refresh its equipment as it aged.

And although a launch to the moon would require smaller instruments than astronomers on the surface of Earth can employ, the frequent visits to the moon that are meant to be the trademark of the Artemis program would suggest that scientists could send larger telescopes than they have to date.

So assuming that scientists can send more mass, keep instruments fresher with maintenance from astronauts, and sort out the dust challenges, what sort of instruments might they send?

Astronomers have plenty of ideas for what they could do with radio telescopes on the moon because such instruments face a major constraint on Earth. The constant barrage of radio signals we generate with our bevy of electronic equipment on the surface and in orbit wreaks havoc on radio observations made from Earth, and the far side of the moon is the only place in the solar system safe from those signals.

That interference means scientists have spent decades imagining the potential of radio observatories on the far side. Such instruments could see into the earliest days of the universe or listen for signals produced by a hypothetical extraterrestrial techno-civilization, for example.

But for other wavelengths, lunar possibilities are a bit less obvious, particularly with only the precedent of a couple ultraviolet instruments to work from, Hammel said. "One reason we have a lot of back and forth about putting telescopes to the moon [is that] the state of the art on the ground, on Earth, and in space has advanced so far during the last 50 years that it's difficult for us to imagine what we would put on the surface in the UV [ultraviolet] and optical and near infrared," Hammel said. "It's difficult to imagine what we would need to build there."

One compelling opportunity, she noted, would be to look back at Earth from the moon as practice for studying worlds beyond our solar system. Exoplanets are compelling scientific targets, but at such great distances scientists struggle to grasp the details of these worlds and interpret what they might look like up close.

"It won't matter that it's a small telescope, because exoplanets, we can't really resolve them anyway," Hammel said. "Being able to study the Earth in multiple phases, multiple wavelengths, over very long time durations, and short time durations, will give us really powerful information for understanding Earth-like exoplanets."

Hammel said ultraviolet observations in general are tantalizing, since such wavelengths can't be studied from Earth's surface. The same atmosphere that protects life on Earth from being fried by ultraviolet radiation also prevents ground-based telescopes from studying astronomical ultraviolet radiation. But there's no atmosphere to interfere on the moon.

Although astrophysicists are still piecing together the details of what lunar observatories could look like, the community is already on board the Artemis program. The first two robotic science freight loads that commercial companies will deliver to the lunar surface as part of the program, which will launch next year, include two astrophysics projects, including a radio astronomy experiment.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.