The search for alien life should broaden its horizons a bit, a new study suggests.

Alien hunters have to date focused largely on Earthlike planets — a reasonable place to start, given that our rocky, water-covered world is the only one we know of that hosts life. But the universe teems with a huge diversity of planets, some of which may be habitable despite being decidedly un-Earthlike.

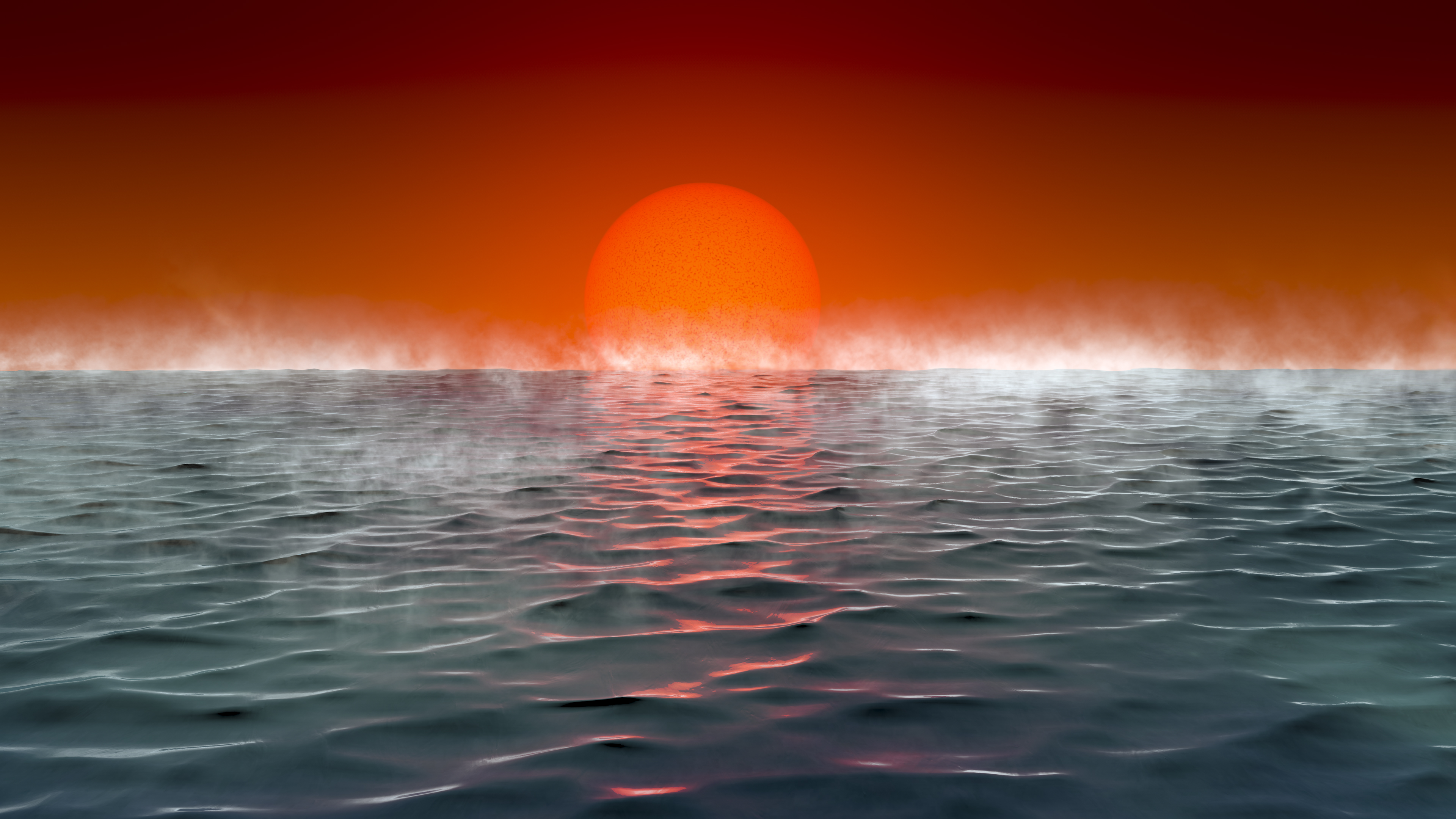

In the new study, researchers identify one such class of alien worlds — "Hycean" planets, which are up to 2.5 times larger than Earth and feature huge oceans of liquid water beneath hydrogen-rich atmospheres. Hycean planets appear to be incredibly abundant throughout the Milky Way galaxy, and they could host microbial life similar to the "extremophiles" that thrive in some of Earth's harshest environments, study team members said.

"Hycean planets open a whole new avenue in our search for life elsewhere," lead author Nikku Madhusudhan, of the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge in England, said in a statement.

Related: 10 exoplanets that could host alien life

Hycean worlds are similar in size to rocky "super-Earths" and gassy "mini-Neptunes," two of the most common types of exoplanet in the galaxy. But the Hyceans are distinct, with densities between those of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes, according to the new study, which was published online Wednesday (Aug. 25) in The Astrophysical Journal.

The Hyceans are also a diverse lot. Some orbit so close to their stars that they're tidally locked, with one scorching-hot dayside and one eternally dark nightside. And some orbit very far away, receiving very little stellar radiation. But life could exist even on such extreme Hyceans, the researchers stress — for example, in the nightside waters of tidally locked worlds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's exciting that habitable conditions could exist on planets so different from Earth," study co-author Anjali Piette, also from Cambridge's Institute of Astronomy, said in the same statement.

In addition, Hyceans appear to be good places to search for potential biosignature gases such as oxygen and methane.

"We find that the larger radii and higher temperatures admissible for Hycean planets make these biomarkers more readily detectable in Hycean atmospheres compared to those of rocky exoplanets," the researchers wrote in the new study.

And a Hycean life hunt could start soon. Madhusudhan and his colleagues identified a number of Hycean worlds whose atmospheres could be scrutinized by next-generation observatories such as NASA's $9.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch later this year. Those potential targets orbit small, dim red dwarf stars between 35 and 150 light-years from Earth.

"A biosignature detection would transform our understanding of life in the universe," Madhusudhan said. "We need to be open about where we expect to find life and what form that life could take, as nature continues to surprise us in often unimaginable ways."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.