First Alien Planet From Another Galaxy Discovered

This story was updated at 2:57 p.m. ET.

Astronomers have confirmed the first discovery of an alien planet in our Milky Way that came from another galaxy, they announced today (Nov. 18).

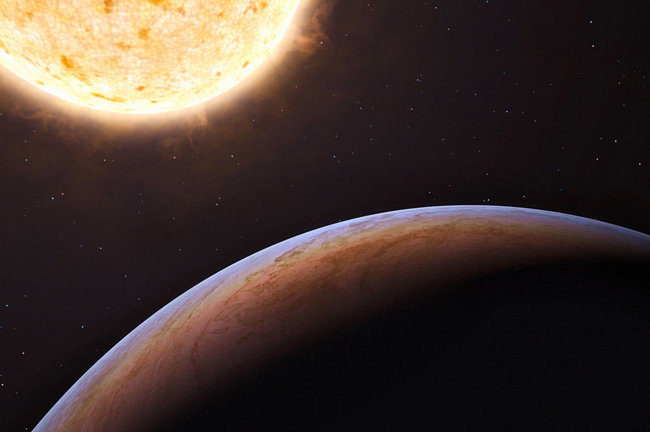

The Jupiter-like planet orbits a starthat was born inanother galaxy and later captured by our own Milky Way sometime between6billion and 9 billion years ago, researchers said. A side effect of thegalacticcannibalism brought a faraway planet within astronomers' reach for thefirsttime ever. [Illustrationof the extragalactic planet]

"This is very exciting," said studyco-authorRainer Klement of the Max-Planck-Institut fur Astronomie (MPIA) inHeidelberg, Germany."We have no ability to directly observe stars in foreign galaxies forplanets and confirm them."

Stars currently residing in othergalaxies are simply toofar away, Klement added.

The find may also force astronomersto rethink their ideasabout planet formation and survival, researchers said, since it's thefirstplanet ever discovered to be circling a star that is both very old andextremely metal-poor. Metal-poor stars are lacking in elementsheavier than hydrogen and helium.

The newfound planet, called HIP13044b, survived through itsstar's red-giant phase, which our own sun will enter in about 5 billionyears.So studying it could offer clues about the fate of our solar system aswell,researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

HIP 13044b sits extremely close toits parent star, whichhas now contracted again. The planet completes an orbit every 16.2days, and itcomes within about 5 million miles (8 million kilometers) of its parentstar atclosest approach — just 5.5 percent of the distance between Earth andthe sun.

Searching for telltale tugs

The newly discovered alienplanet isat least 25 percent more massive than Jupiter, researchers said. Itorbits thestar HIP 13044 about 2,000 light-years from Earth in the constellationFornax.

HIP 13044 is about as massive as the sun, and it is nearingthe end of its life. The star has already gone through its red giantphase —when sun-like stars bloat enormously after exhausting the hydrogen fuelintheir cores.

The star is also composed almostentirely of hydrogen andhelium. It is less than 1 percent as metal-rich as our sun, makingit themost metal-poor star known to host a planet, researchers said.

The research team scrutinized HIP13044's movement using atelescope at the European Southern Observatory's La Silla Observatoryin Chile.After six months of observing, they detected tiny movements thatbetrayed thegravitational tug of an orbiting planet.

"For me, it was a big surprise," saidstudy leadauthor Johny Setiawan, also of MPIA. "I was not expecting it in thebeginning."

Setiawan, Klement and theircolleagues report their resultsonline in the Nov. 18 issue of Science.

An extragalactic origin

Last year, another research teamannounced it may havedetected a planet in the Andromeda galaxy. However, that faraway findwill benearly impossible to confirm.

The astronomers performing thatprevious study used a methodcalled gravitationalmicrolensing, which only works when a planet-hosting starhappens to lineup with another star. Such events happen very rarely.

HIP 13044, on the other hand, belongsto the Helmi stream ofstars that were once part of a nearby dwarf galaxy. Astronomers believeour ownMilkyWay gobbled up the Helmi stream between 6 billion to 9billion years ago.

While it's technically possible thatthe planet was bornin the Milky Way and then stripped from its parent star by the interlopingHIP13044, the odds of that happening are minuscule, researchers said.

So HIP 13044 almost certainly has anextragalactic origin.

"We can be pretty sure about that,"Klement toldSPACE.com. "Stellar encounters in the Milky Way essentially don'toccur.The chance that the star captured the planet from another star by anencounteris very, very unlikely."

Rethinking theories ofplanet formation

Most of the nearly500 alien planets discovered so far orbit metal-rich stars,researcherssaid. And a metal-rich star is fundamental to the dominant theoryexplaininghow giant planets form — the core-accretion model.

This model posits that dust and gasparticles circling ayoung star cling together and gradually become larger, forming rocks,bouldersand eventually the stony cores of giant, gassy planets like HIP 13044b.

Because its parent star is sometal-poor, HIP 13044b mayhave formed in a different way, researchers said. The planet may havearisenvia the gravitational attraction between gas molecules, through aprocesstermed the disk-instability model. So it may not have a rocky core atall.

"You are able to form pure gasplanets by this method,"Klement said.

The fact that such a metal-poor starcan host planets shouldinspire astronomers to look at other stars like it, Klement added.Astronomershaven't examined many up to this point, so they don't have a goodhandle on howfrequently planets might pop up around low-metal stars.

The discovery also hints that planetsmay have studded thecosmos from the universe's early days — back when pretty much all starsweremetal-poor.

"You can think of the very firststars in the universe,or the second or third generation of stars," Klement said. "Couldthey already have been able to form planets? That's a very fascinatingquestion."

Vision of our solar system'sfate?

Our own sun is on the samestellar-evolution track as HIP13044; scientists predict it will bloatinto a red giant in 5 billion years or so. So astronomers maybe able tolearn something about the fate of our solar system by studying HIP10344b andits parent star, researchers said.

That fate would not be pretty forEarth. HIP 13044b likelyonce orbited much farther away from its star but spiraled closer andcloserduring the red giant phase due to friction with the swollen star'senvelope,researchers said. Any more interior planets would have been destroyedduringthis process.

When our own sun enters its red giantphase, Earth willlikely get cooked.

"The inner planets, including Earth,maybe will notsurvive," Setiawan told SPACE.com. "But Jupiter, Saturn and the outerplanets might move to closer-in orbits, exactly like we detected."

HIP 13044b is a survivor, but itwon't live forever. Itsparent star is due to expand again in the next phase of its stellarevolution,researchers said, and this time the planet will almost certainly beengulfed.

- Gallery:Strangest Alien Planets

- Top10 Star Mysteries

- Determining500th Alien Planet Will Be a Tricky Task

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.