Heftiest Star Discovery Shatters Cosmic Record

Astronomers have discovered the most massive stars known, including one at more than 300 times the mass of our sun — double the size that scientists thought heavyweight stars could reach.

These colossal stars are millions of times brighter than the sun and shed mass through very powerful winds.

The stellar discovery, which represents the first time that these hulking stars were individually identified, could help astronomers understand the behavior of massive stars, and how large they can be at birth.

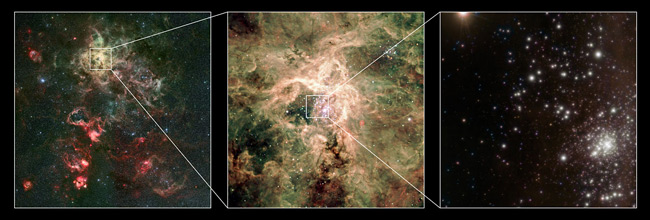

A European research team led by Paul Crowther, professor of Astrophysics at the University of Sheffield in England, discovered the massive stars inside two young clusters of stars — NGC 3603 and RMC 136a. They used a combination of instruments on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, in addition to archival data from the Hubble Space Telescope, to study the stellar nurseries.

The NGC 3603 nebula, located 22,000 light-years from the sun, is a star-making factory where flurries of stars form from the extended clouds of gas and dust.

RMC 136a, which is more commonly referred to as simply R136, is another cluster of young, massive and hot stars, located within the Tarantula Nebula. This nebula is found in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighboring galaxy that is 165,000 light-years away.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers found several stars with scorching hot surface temperatures of over 71,500 degrees Fahrenheit (39,700 degrees Celsius), which is more than seven times hotter than the sun. The stars are also tens of times larger and several million times brighter.

The researchers compared their observations with models, and their findings suggest that a number of these stars were greater than 150 solar masses at birth.

In fact, the star R136a1, which is located in the R136 cluster, is the most massive star ever found. Its current mass is approximately 265 solar masses, and its estimated birth weight was as much as 320 times that of our sun. R136a1 also has the highest luminosity of any star found to date — nearly 10 million times greater than the sun.

Big, fat baby stars

From the time of their birth, these massive stars produce outflows, such as powerful winds, which eventually reduce their mass, researchers said.

"Unlike humans, these stars are born heavy and lose weight as they age," Crowther said. "Being a little over a million years old, the most extreme star R136a1 is already 'middle-aged' and has undergone an intense weight loss program, shedding a fifth of its initial mass over that time, or more than 50 solar masses."

The stars are still, however, intensely bright.

For example, if the star R136a1 were to replace the sun in our solar system, it would outshine our closest star by as much as the sun currently outshines the full moon, and its powerful radiation would effectively sterilize our home planet.

"Its high mass would reduce the length of the Earth's year to three weeks, and it would bathe the Earth in incredibly intense ultraviolet radiation, rendering life on our planet impossible," said Raphael Hirschi, a research team member from Keele University in Staffordshire, England.

More massive than thought

In the NGC 3603 nebula, the astronomers were also able to directly measure the masses of two stars that belong to a double-star system. The stars A1, B and C in this cluster have estimated birth masses of close to or above 150 solar masses.

These ultra-heavy stars are extremely rare and only form within the densest star clusters. Detecting them requires the sharp resolving power of the Very Large Telescope's infrared instruments.

In the study, the researchers estimated the maximum possible mass for stars within the two clusters, and the relative number of the most massive stars. Their findings have caused them to reevaluate current estimates for how large these stars can be.

"The smallest stars are limited to more than about 80 times more than Jupiter, below which they are 'failed stars' or brown dwarfs," said Olivier Schnurr, a research team member from the Astrophysikalisches Institut Potsdam in Germany. "Our new finding supports the previous view that there is also an upper limit to how big stars can get, although it raises the limit by a factor of two, to about 300 solar masses."

Within R136, only four of the approximately 100,000 stars found in the cluster weighed more than 150 solar masses at birth. Yet the sheer intensity of their wind and radiation account for nearly half of R136's entire wind and radiation power.

R136a1 alone emits energy by more than a factor of 50 compared to the entire Orion Nebula, which is the closest region of massive star formation to Earth.

Unraveling the mystery

Astronomers are still grappling to understand how these stars form — a process further complicated by their very short life spans and powerful winds.

"Either they were born so big or smaller stars merged together to produce them," Crowther said.

Stars between approximately eight and 150 solar masses end their brief lives in supernova explosions, leaving behind exotic remnants in the form of either neutron stars or black holes.

With the discovery of stars weighing between 150 and 300 solar masses, the study's findings raise the prospect of the existence of exceptionally bright, "pair instability supernovae" that blow themselves apart. These exploding stars fail to leave any remnants, and disperse up to ten solar masses of iron into their surroundings. A few candidates for such explosions have been proposed in recent years.

Still, the title of most massive star ever found now belongs to R136a1, and the stellar heavyweight could hold the designation for quite some time, said Crowther.

"Owing to the rarity of these monsters, I think it is unlikely that this new record will be broken any time soon," he said.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.