Study: Earth-like Planets Common

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

BOSTON — Rocky planets like Earth could be found around most sun-like stars in our galaxy, new research suggests, further raising hopes that scientists will someday find ET or at least primitive life beyond our solar system.

The finding is based on an analysis of dust around 309 stars with masses comparable to our sun.

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope was able to detect the heat that radiated from the dust, "not unlike the smoke you'll see rising from chimneys around here in the Boston area on a cold day," said researcher Michael Meyer of the University of Arizona.

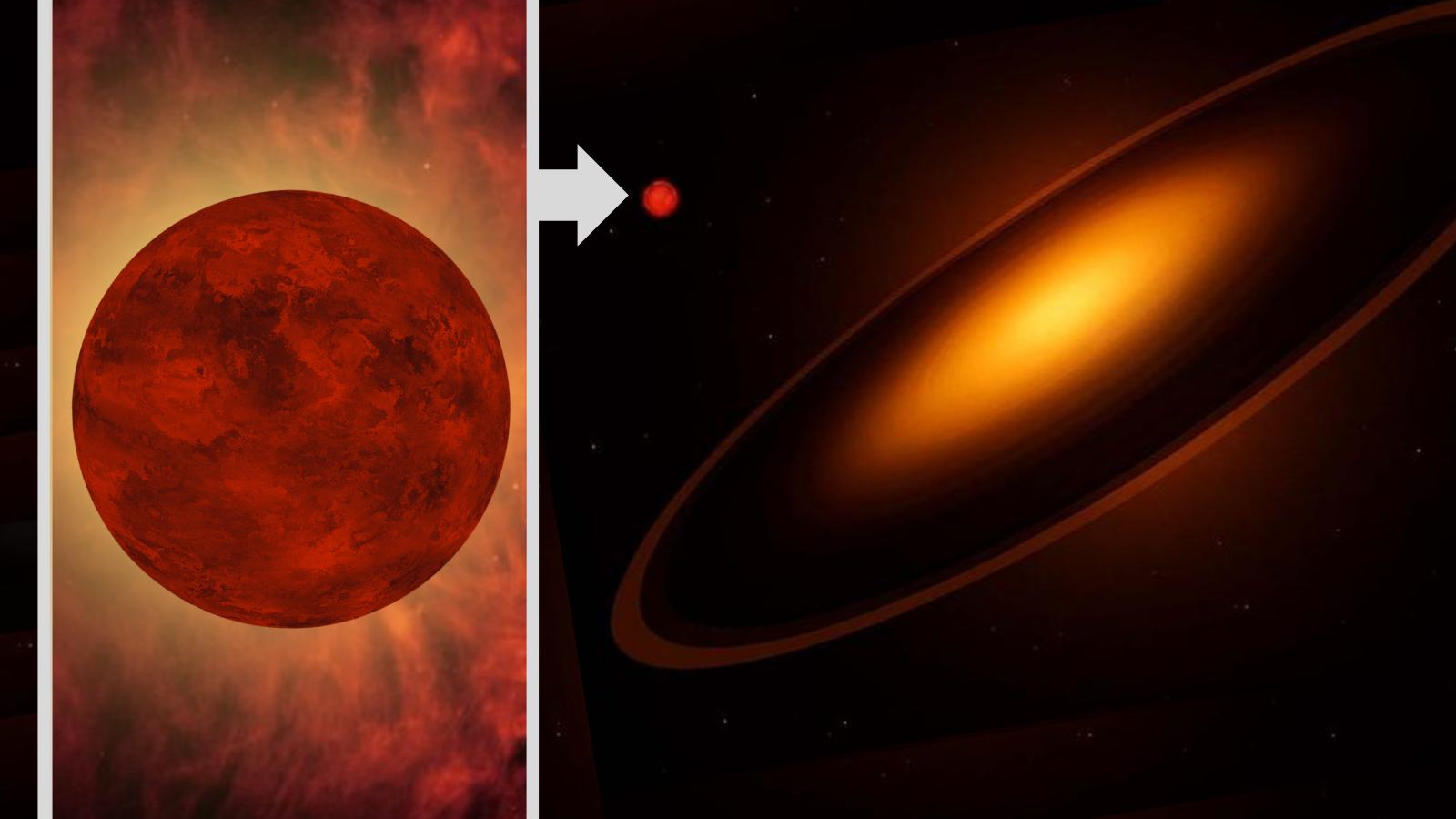

Meyer and his colleagues found "warm" dust, between minus 280 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit, orbiting the stars at an estimated distance from their stars in the same range that Earth and Jupiter are found in our solar system. This allowed them to infer the presence of colliding larger rocky bodies and to estimate that at least 20 percent and up to as many as 60 percent of stars like our sun in the disk of our galaxy could give rise to rocky planets like Earth.

"From those observations of dust, we infer the presence of colliding larger rocky bodies, not unlike asteroids and other things in our solar system that we know bang together and generate dust," Meyer told reporters here at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). "By tracing that dust, we trace these dynamical processes that we think led to the formation of the terrestrial planets in our solar system."

The best guess scientists have for the time scale of the formation of Earth, as a result of collisions, is when our sun was between 10 million to 50 million years old (it is now about 4.6 billion years old). Meyer found the warm dust trails in stars between 3 million and 300 million years old.

The results are detailed in the Feb. 1, 2008, issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Still no consensus on planet definition

Since the late 1990s when astrophysicists started finding evidence of planets beyond our solar system, more than 250 now have been found, and it has become more and more unclear what exactly a planet is. The International Astronomical Union arrived at a new formal definition a couple years ago, but scientists still disagree.

In fact, Meyer says he is less interested at this point in what the definition is.

"I am interested in how common different masses of objects are and their sizes are from the inner solar system to the outer solar system," Meyer said. "That will tell us a lot about how our solar system evolved ... Really the question is, 'How common are planetary systems like our own around sun-like stars in our galaxy?'"

The diversity of exoplanets now found is broad in terms of size and proximity to their parent suns, said astronomer Debra Fischer of San Francisco State University. And the planets resemble the creativity in architecture that you might get from a "school child" if you gave the kid clay and asked him or her to model planets in a solar system. Fischer, Meyer and a few other planetary scientists were set to present their research in detail to scientists on Monday at the AAAS.

The materials necessary for carbon-based life in the universe, including water, are common, scientists have found. The trick is to finding planets in the right location, Fischer said.

"To my mind, there's two things we have to go after," Fischer said. "We have to find the right mass planet and it has to be the right distance from the star," she said. The trouble is that these "right-mass, right-place planets are in the anti-sweet spot for every [detection] technique that exists now."

Planetary scientists are looking forward to more data on exoplanets in coming years if all goes well with NASA's Kepler Mission, set to launch in February 2009 and designed to survey our region of the Milky Way galaxy to detect and characterize hundreds of Earth-size and smaller planets that are close enough (but not too close) to their stars to support possible life. A similar French mission, COROT, is already making observations.

New view of our solar system

The findings of the past decade have yielded a "revolution" in scientific thinking about our solar system, said planetary scientist Alan Stern, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate.

A couple decades ago, Pluto was thought to be in the outer solar system, but scientists now see Pluto in the middle of the solar system. A vast ring of small objects beyond Pluto, called the Kuiper Belt, is now seen as the outer solar system, Stern said.

Also, scientists used to think that our planets formed pretty much where we see them today. Now evidence suggests that planets migrate a great deal early in their lives. Also, evidence suggests that many more planets existed in our solar system than the eight major planets we now count, Stern said.

Scientists might even find objects the size of dwarf planets, (currently the only recognized dwarf planets are Pluto, Ceres and Eris), or even the size of Mars and the gas giant planets, in the solar system's Oort Cloud of dust, located even beyond the Kuiper Belt (although the distinction between the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud is coming into question among scientists), Stern said.

- Solar System Like Ours Found

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Video: Planet Hunters

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.