Blood Moon of January 2019: 5 Questions Answered for the Total Lunar Eclipse

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

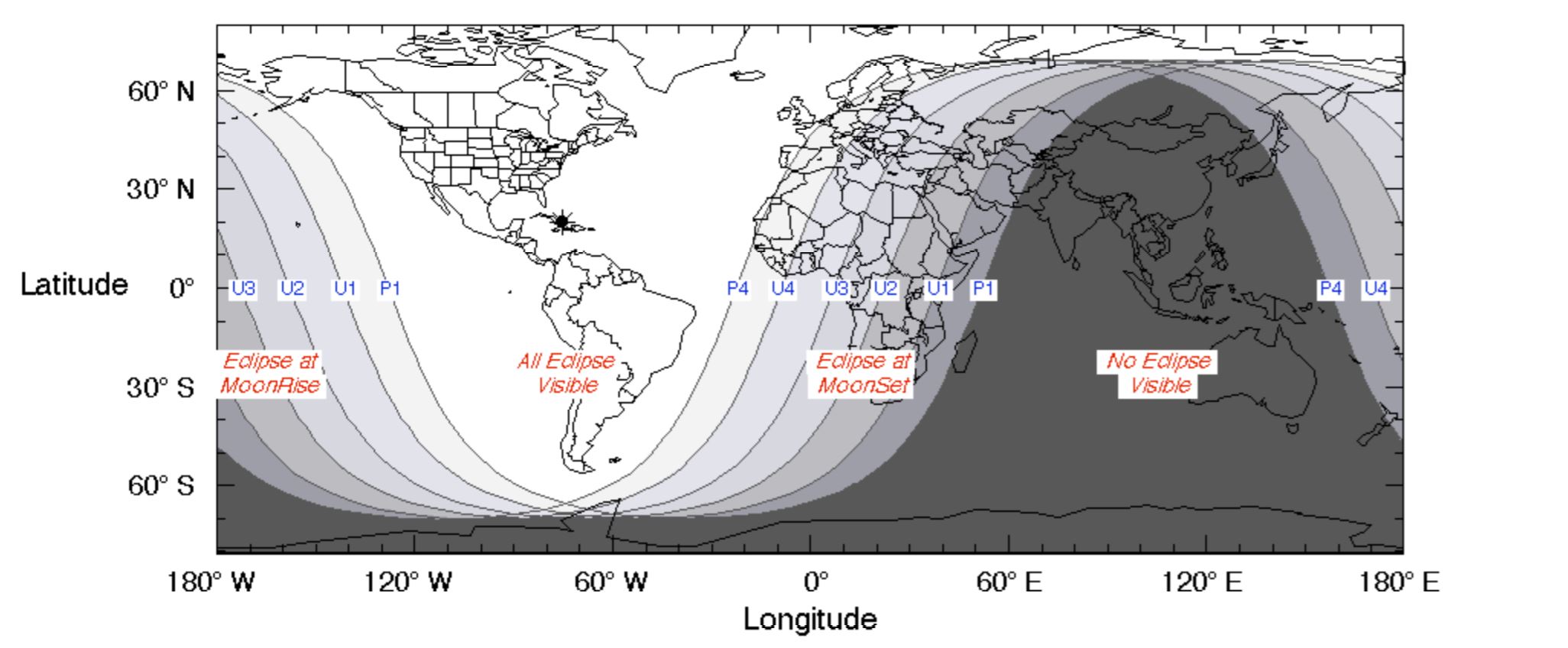

A total lunar eclipse will appear overnight from Sunday (Jan. 20) to Monday (Jan. 21), and the potentially copper-colored moon — dubbed a "blood moon" — will be visible from all of North and South America.

A lunar eclipse can occur only during a full moon phase. And since this full moon will appear to be one of the largest of 2019, NASA also describes the lunar eclipse's full moon as a "super" moon. The term has only been used in the past few decades, and became especially popular during the three consecutive supermoons of late 2016.

Walter Freeman, a physicist at Syracuse University, answered five popular questions about the enthralling event that will be visible to millions of people this month. [Super Blood Moon Lunar Eclipse of January 2019: Complete Guide]

Should those watching the lunar eclipse be aware of anything when they look up?

"There are no precautions you need to take when observing a lunar eclipse, since the moon is never bright enough to hurt our eyes like the sun is," Freeman saidin a Jan. 9 statement from Syracuse University. "A blood moon is one of the few opportunities we have to see both the moon and the stars in the sky at the same time, since the moon is usually too bright!"

How often does this sort of eclipse happen?

"There is a little less than one total lunar eclipse per year on average," Freeman said. Lunar eclipses don't occur every month because the moon's orbit is tilted, "so usually when the moon is full, the Earth's shadow passes a little bit above or a little bit below it." That's why most months don't have a lunar eclipse. The super blood moon of Jan. 21 will occur this time around because the moon will pass through the top portion of Earth's shadow.

What should viewers expect to see?

Minutes after 10:30 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, or shortly past 7:30 p.m. Pacific Standard Time, Earth's shadow will start passing in front of the moon from the lower left, he said, and about an hour later, the full lunar eclipse appears. This totality lasts roughly another hour, and at about 1:45 a.m. EST on Jan. 21 (10:45 p.m. PST on Jan. 20), the full moon will return to its normal appearance.

Why is a total lunar eclipse called a blood moon?

"A little bit of sunlight is refracted by the Earth's atmosphere… bending around the edges of the Earth" before reaching the moon, causing the reddish tint. The moon doesn't disappear from sight, but does become "10,000 or so times dimmer than usual."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When will a total lunar eclipse be visible from North America after Jan. 21?

"The next total solar eclipse visible from the United States will be on Nov. 8, 2022 — visible as the moon sets in the West just before sunrise," Freeman said.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.