Baby Exoplanet Weighed for First Time

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Astronomers have measured the mass of a very young alien planet for the first time, thanks to more than two decades' worth of data collected by two of the European Space Agency's star-mapping satellites.

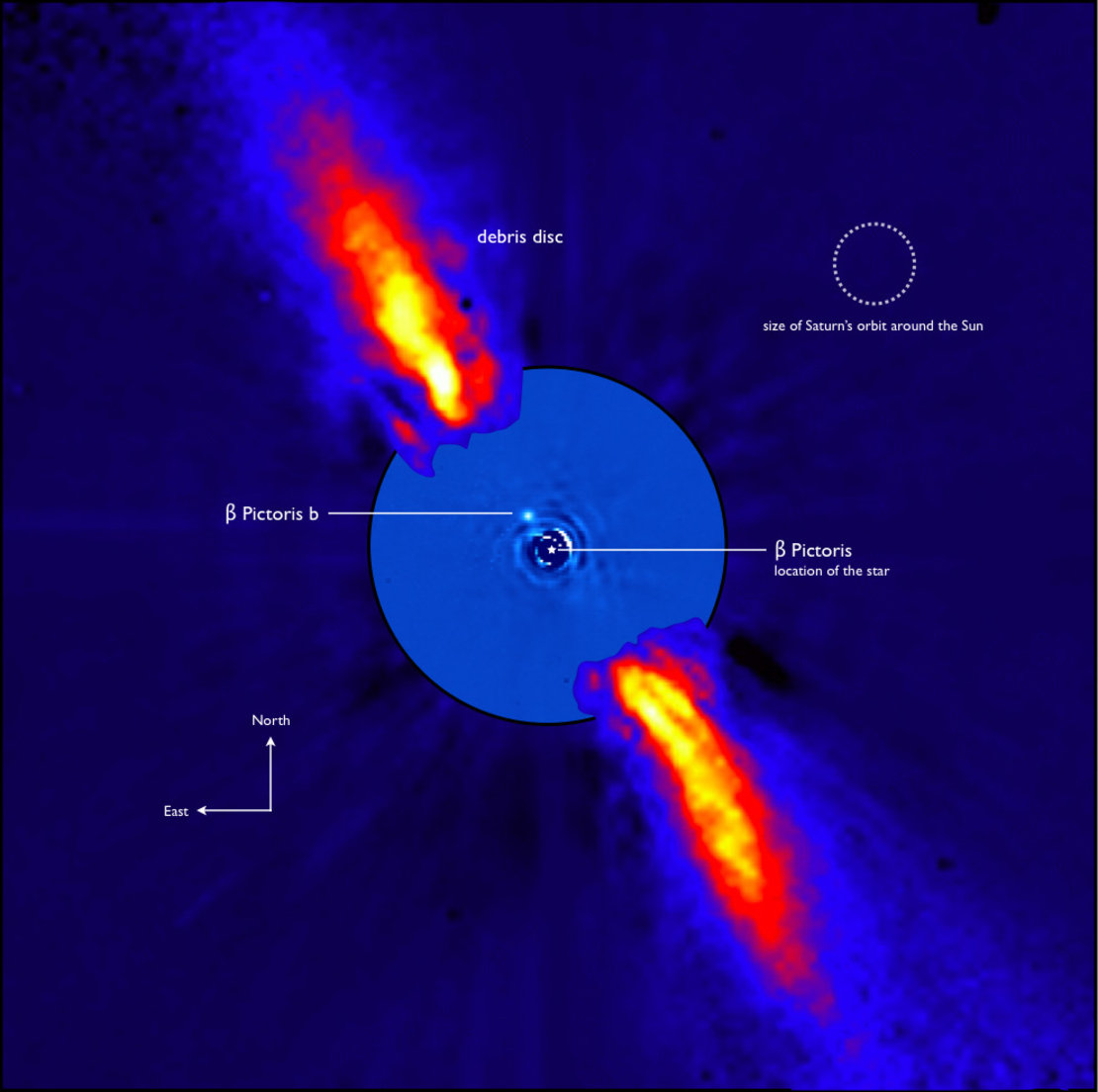

The exoplanet — known as Beta Pictoris b — is a gas giant like Jupiter, but scientists estimate it is nine to 13 times more massive than our solar system's biggest planet. Discovered in 2008, this exoplanet orbits the star Beta Pictoris, the second brightest star in the constellation of Pictor.

Because this star is still very young, it demonstrates how planets form and evolve. However, because the star is still forming and pulsing with activity, it's challenging for astronomers to accurately measure the star's radial velocity (speed as the star moves toward and away from Earth as its planet orbits). This is a method commonly used to estimate the mass of exoplanets. [Beta Pictoris b in Pictures: An Alien Planet Image Gallery]

Instead, the weight of Beta Pictoris b was calculated based on the position and motion of its host star in the sky over a long period of time, according to a statement from ESA.

"The star moves for different reasons," Ignas Snellen, lead author of the study and astronomer from Leiden University, the Netherlands, said in the statement. "First, the star circles around the center of the Milky Way, just as the sun does. That appears from the Earth as a linear motion projected on the sky. We call it proper motion. And then there is the parallax effect, which is caused by the Earth orbiting around the sun. Because of this, over the year, we see the star from slightly different angles."

The researchers also detected "tiny wobbles" in the star's motion, which means the star deviates from its expected course due to the gravitational pull of Beta Pictoris b, according to the statement.

"We are looking at the deviation from what you [would] expect if there was no planet, and then we measure the mass of the planet from the significance of this deviation," Anthony Brown, co-author of the study and researcher from Leiden University in the Netherlands, said in the statement. "The more massive the planet, the more significant the deviation."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, in order to accurately estimate the mass of Beta Pictoris b, the researchers needed to collect observations over a long period of time. This required combining data from the Gaia spacecraft (launched in 2013) and the ESA's Hipparcos satellite, which studied Beta Pictoris 111 times between 1990 and 1993. Combining measurements from the two spacecraft revealed that the infant exoplanet is between nine and 13 times more massive than Jupiter, according to the statement.

"By combining data from Hipparcos and Gaia, which have a time difference of about 25 years, you get a very long-term proper motion," Brown said. "Hipparcos on its own would not have been able to find this planet, because it would look like a perfectly normal single star unless we had measured it for a much longer time."

The findings were published Aug. 20 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.