Dwarf Planet Ceres' Bizarre Bright Spots Shine in Stunning Up-Close View

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

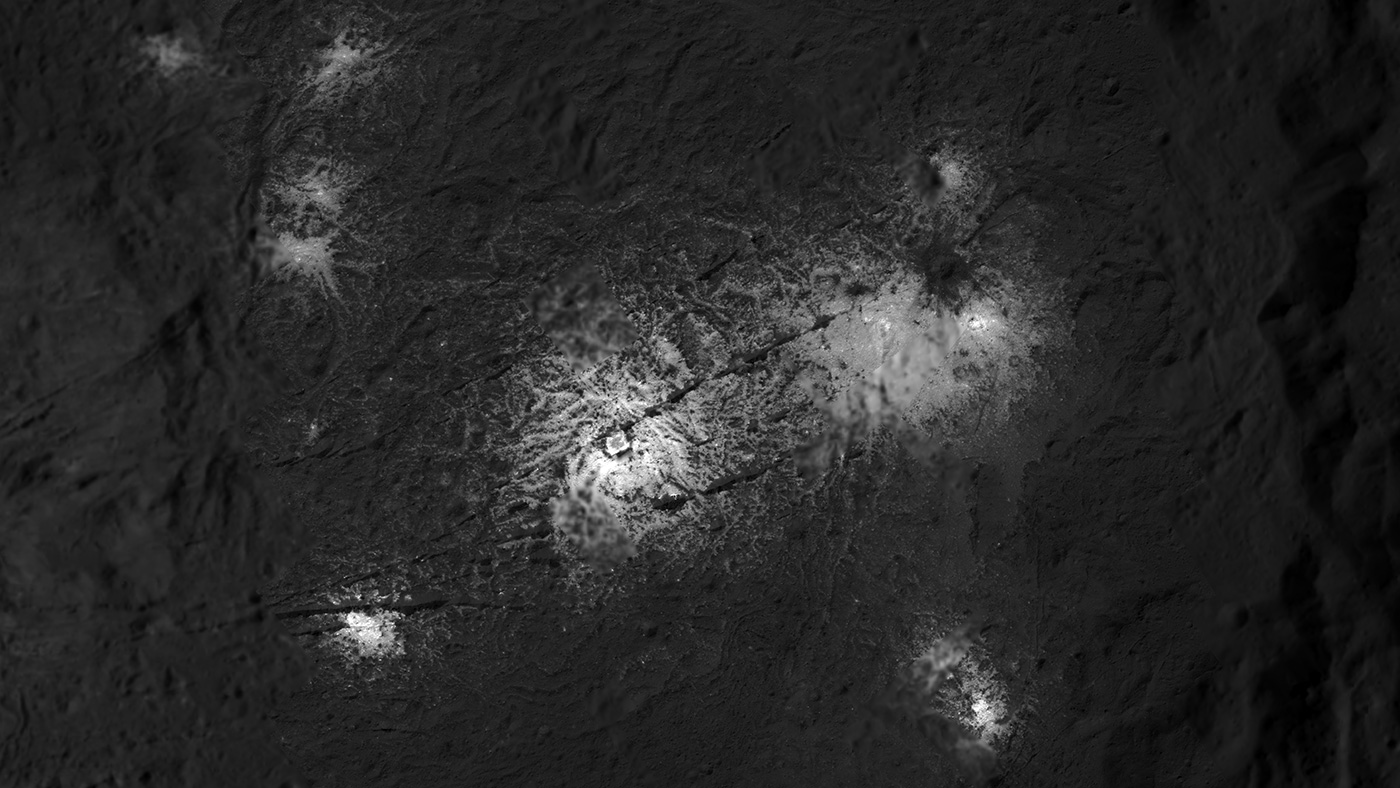

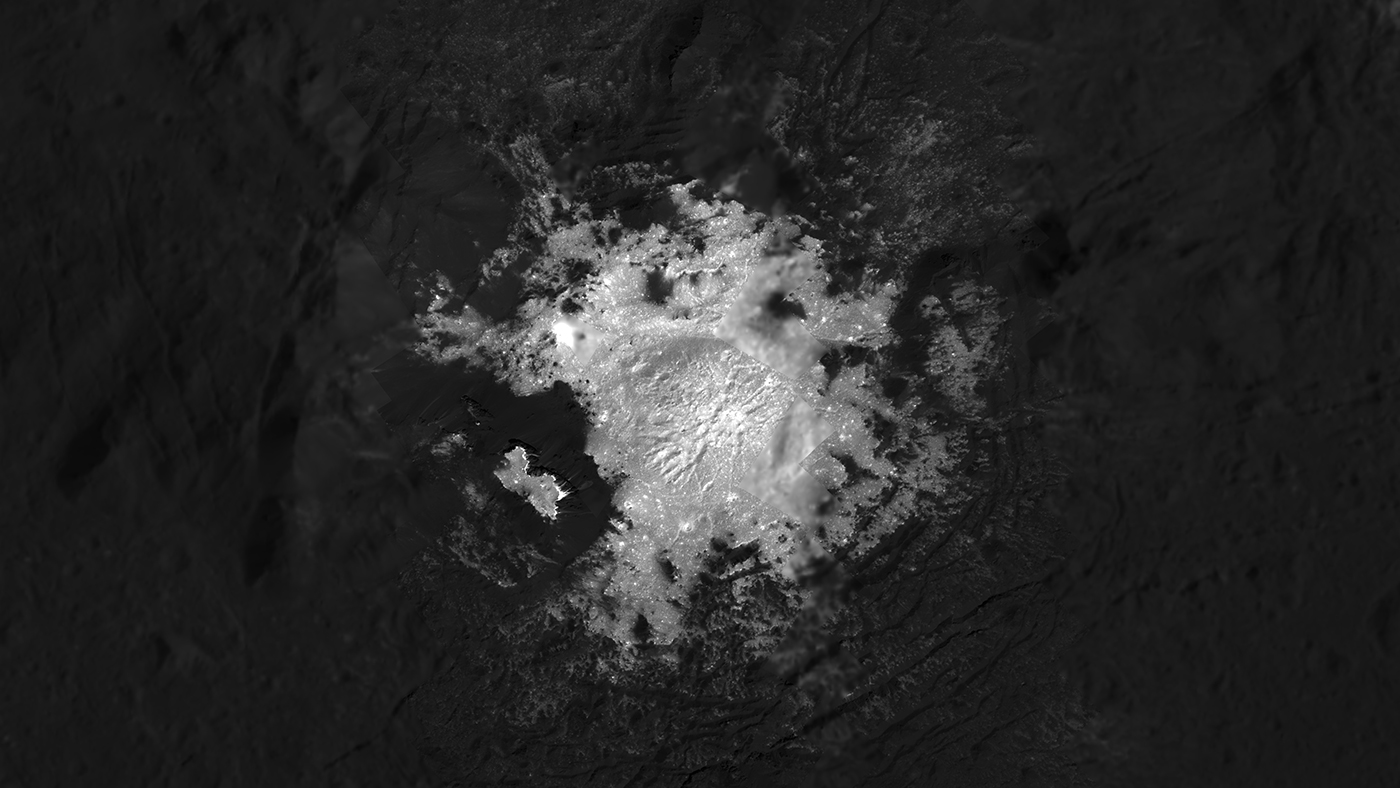

You may have seen the bizarre bright spots speckling the dwarf planet Ceres — but not like this.

NASA's Ceres-orbiting Dawn spacecraft has captured jaw-dropping new photos of several of the bright-white features, formally known as faculae, that lie at the bottom of the dwarf planet's 57-mile-wide (92 kilometers) Occator Crater.

Dawn snapped the images from an elevation of about 21 miles (34 km) — just three times higher than a commercial airliner flies, NASA officials said. [In Pictures: The Changing Bright Spots of Dwarf Planet Ceres]

"The new images of Occator Crater and the surrounding areas have exceeded expectations, revealing beautiful, alien landscapes," Dawn principal investigator Carol Raymond, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement yesterday (July 16).

The $467 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007 with a bold goal: to orbit and study the two largest bodies in the asteroid belt: Vesta and Ceres. Both objects are considered leftovers from the solar system's planet-formation period (hence the mission's name).

Dawn reached Vesta in July 2011 and eyed the object up close for more than a year, finally leaving for Ceres in September 2012.

Dawn discovered the Occator Crater bright spots during its approach to Ceres in early 2015, and later found a number of other crater-associated faculae around the dwarf planet. The probe's observations have since revealed that the bright spots are salty deposits, composed primarily of sodium carbonate and ammonium chloride.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists think this material was left behind when briny water boiled away into space, but they're not sure where, exactly, those brines came from — specifically, how deep underground the reservoirs were.

Dawn team members are using the probe's observations to tackle this and other questions about the 590-mile-wide (950 km) Ceres. Some of the most intriguing data and eye-popping photos come from Dawn's most recent mission phase, during which the probe has circled above Ceres at an altitude of just 21 miles or so.

Dawn spiraled down to this superlow orbit early last month and will remain there through the end of its operational life, which is expected to come in a few months. The spacecraft is nearly out of hydrazine, the fuel that powers Dawn's small orientation-controlling thrusters. When the hydrazine is gone, Dawn will be unable to point its science instruments at Ceres, or its communications gear at Earth.

The Dawn team is presenting the results from the latest (low-orbit) mission phase this week at the Committee on Space Research conference in Pasadena.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.