Full Moon Shines with Saturn at Opposition Tonight: How to See Them

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Late Wednesday night (June 27), the moon and Saturn will be extremely close in the sky, and both will be opposite from the sun — a lineup that will attract the attention of even casual skywatchers.

Sometimes, sky almanacs referencing the position of the planets will use the term "opposition." But what exactly does that mean? As seen from our vantage point here on Earth, opposition refers to whenever a planet is located in the sky in a position that's directly opposite to the sun.

This is also the time when the planet in question appears at its best position for observation. For all intents and purposes, it is in the sky all night long: rising in the east as the sun is setting in the west, reaching its highest point in the sky at midnight (or 1 a.m. if daylight saving time is in effect), and setting in the west as the sun is about to rise in the east. [When, Where and How to See the Planets in the 2018 Night Sky]

This situation happens only for the so-called superior planets — that is, planets that are located farther from the sun than they are from Earth. Of the bright, naked-eye planets, only Mars, Jupiter and Saturn can appear in opposition, or diametrically opposite to the sun in our sky.

The two "inferior" planets, Mercury and Venus, can never appear opposite to the sun because they are situated closer to the sun than they are to Earth. Instead, the best time to try to see these two inner worlds is when they are at greatest elongation, which is their greatest angular distance from the sun. Mercury can pull far enough away from the sun to be visible for up to 90 minutes before sunrise or after sunset. Venus can be visible for as much as 4 hours before sunrise or after sunset. But neither planet can remain in view for an entire night.

Opposition intervals

In the case of a superior planet, three celestial bodies must be in proper alignment in this order: sun, Earth and planet. Earth, of course, is in the middle, flanked by the sun on one side and the planet in question on the other.

Put another way, when Earth, which takes one year to move around the sun, passes (or "laps") a slower outer planet, that is the moment of opposition. Because Mars takes 684 days to make one trip around the sun, Earth catches up to Mars about every 2.2 years. Mars will come to opposition on July 27 of this year. Its next opposition will come in October 2020, followed by another in December 2022.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jupiter moves around the sun much more slowly than Mars, taking nearly 12 years to make one complete orbital circuit. For this largest of all planets, oppositions come roughly one month later each year. Jupiter was at opposition this year on May 10. Next year, opposition will come on June 12, and in 2020, it will happen on July 15.

To the ancient starwatchers, before they knew about more distant worlds like Uranus and Neptune, Saturn was known as the most distant planetary wanderer. Saturn was the Roman equivalent of the Greek god Cronus, the god of time. And to the ancients, Saturn seemed to take a lot of time moving from one zodiacal sign to another — in some cases, up to two and a half years. In fact, Saturn takes 29 and a half years to orbit the sun. For this reason, oppositions of Saturn come only about two weeks later in the calendar each year.

Saturn and the moon will align

Saturn will arrive at opposition to the sun this week. It happens on Wednesday; the moment that it will be directly opposite to the sun will occur at 1300 GMT. That's 9 a.m. EDT and 6 a.m. PDT. Of course, Saturn will not be visible at these times across North America, as it will be daytime.

Skywatchers in this region will have to wait until later that evening, after sunset, to see Saturn low in the east-southeast sky. But it will not rise alone; it will keep company with the moon, which will be practically full. In fact, another way to define a "full" moon would be to say that the moon is at opposition. Full phase happens when the moon is opposite to the sun in the sky and its entire disk is fully illuminated by sunlight. That happens at intervals of about 29.5 days. The moment of full phase will come at 0453 GMT on Thursday morning, or 12:53 a.m. EDT and 9:53 p.m. PDT on Wednesday night. [Full Moon Calendar 2018: When to See the Next Full Moon]

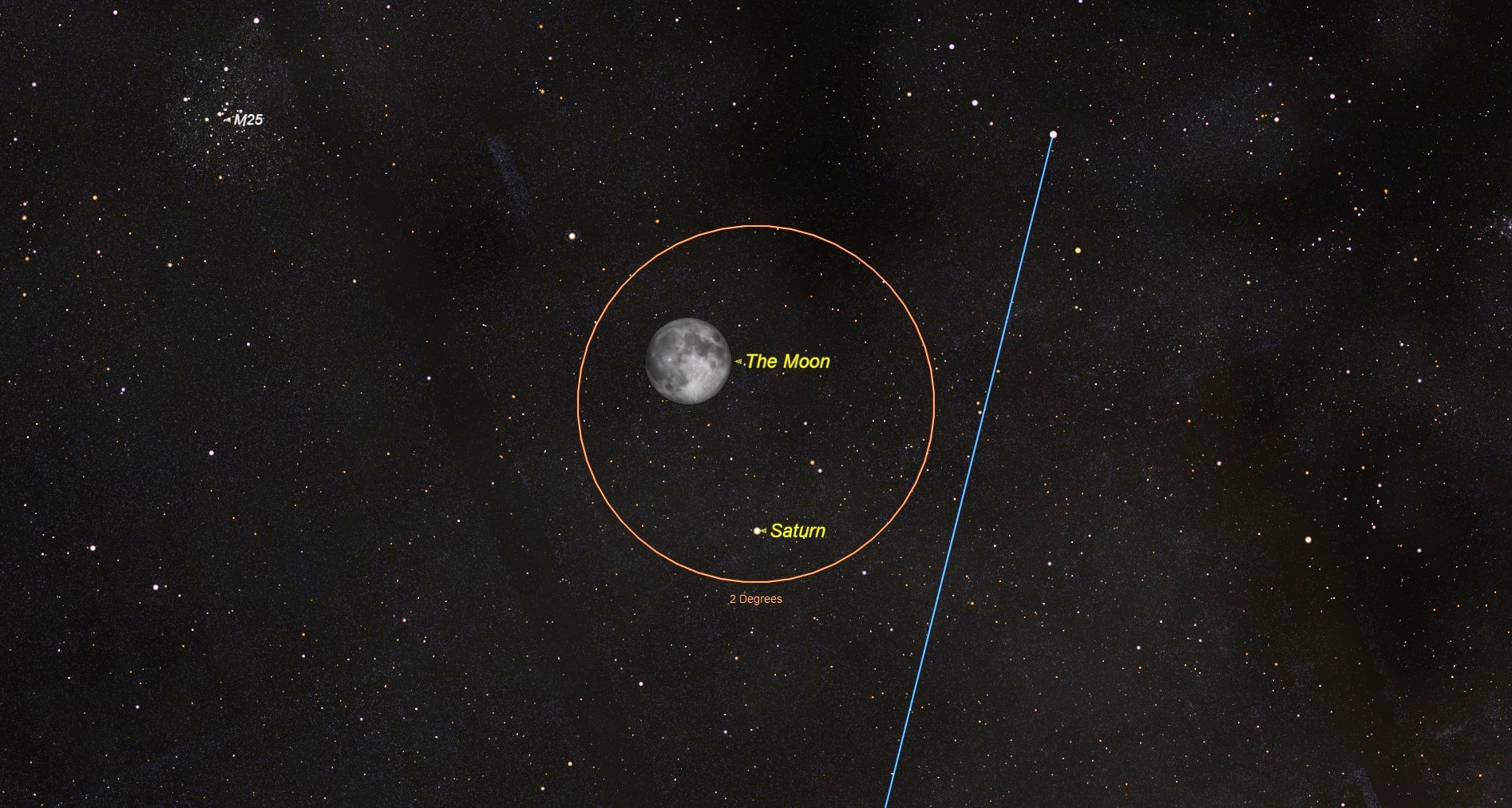

Or, put yet another way, the moon will reach a point in the sky opposite to the sun 15 hours and 53 minutes after Saturn does. And along the way to arriving at full phase, the moon will pass rather close to Saturn. In the sky, the moon will appear to the upper left of Saturn as both rise above the east-southeast horizon on Wednesday evening.

Depending on your location, however, the view will be somewhat different. For those in the Eastern time zone, the moon and Saturn will be closest together — about 1 degree apart — at around 11:30 p.m. In the Central time zone, the pair will be closest at around 10 p.m. From the Mountain time zone, the moon and Saturn will be closest at around 9 p.m., in bright twilight. For the Pacific states, the time of closest approach will coincide with local sunset (around 8:30 p.m.), and the gap between the two will have widened to about 1.3 degrees.

The Seeliger effect

When a superior planet is at opposition, it will also be near the point in its orbit where it is closest to Earth, which means it will also be shining with its greatest radiance. In the case of Saturn, it will appear to glow sedately with a yellow-white hue of magnitude 0.0. To compare that with the brightest stars of the summer, blue-white Vega and orange Arcturus, Saturn's brightness will match Vega's and appear only a trifle dimmer than Arcturus'. At that brightness, there will be no problem in seeing Saturn visually, in spite of its proximity to the dazzling full moon.

And if you train a telescope on Saturn, its famous ring system will also appear a bit brighter than normal, but for a different reason. The rings are composed of a multitude of highly reflective ice particles ranging in size from dust to boulders, grouped in complex subsystems of rings within rings. And for a day or two before and after opposition, the shadows of these icy particles will be hidden, just as sunlight is hitting the rings straight on. As a consequence of this geometry, the rings appear to surge in brightness compared to the planet's gaseous globe. This brightness enhancement — known today as the Seeliger effect — is named for the German astronomer Hugo von Seeliger (1849-1924), who used it as circumstantial evidence that the mysterious rings were actually composed of individual particles rather than being made of solid disks.

So while there is no question that this summer will certainly belong to Mars because of its unusually close approach to Earth in late July, at least on Wednesday night, attention will be focused on "The Lord of the Rings," which will appear at its very best in 2018. And accompanying it across the sky from dusk till dawn on that same night will be our nearest neighbor in space.

Joe Rao serves an associate at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in the Lower Hudson Valley of New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.