Dangling on a Wire: A Tale from the Making Of '2001: A Space Odyssey'

Michael Benson is an artist, writer and filmmaker whose previous books include "Cosmigraphics: Picturing Space Through Time" and "Planetfall: New Solar System Visions." His latest book, "Space Odyssey," documents the making of the iconic film "2001: A Space Odyssey," which celebrates its 50th anniversary in April 2018. In this excerpt from "Space Odyssey," Benson describes the extraordinary (and quite literally suffocating) lengths Stanley Kubrick went to — with the help from stuntman Bill Weston — to film a realistic spacewalk.

You can read a Q&A with Benson on his new book here.

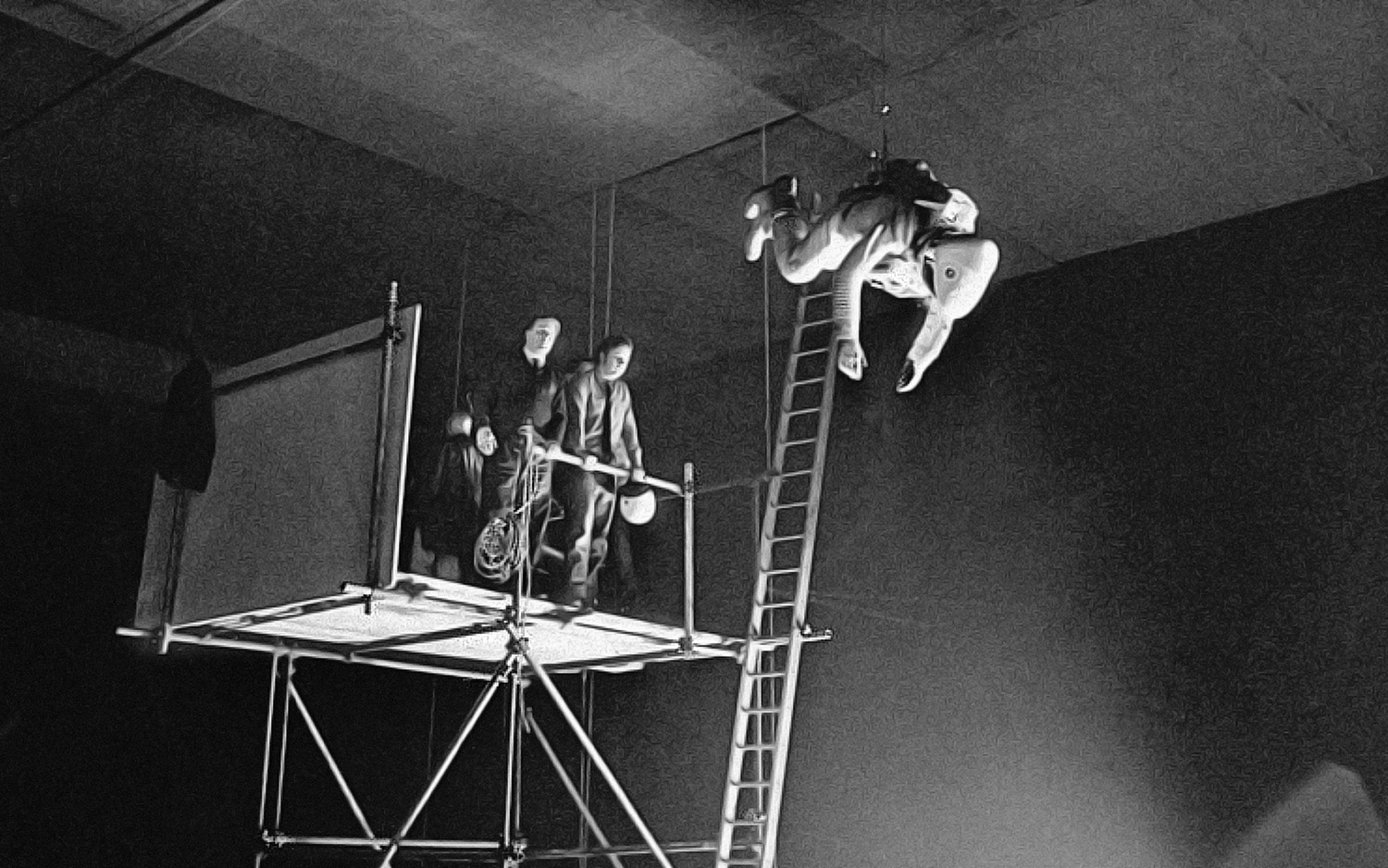

Perhaps the single most extraordinary sight during the film's production could be seen high above Stage 4 on certain days in July, August, and into the fall of 1966. That was where stuntman Bill Weston was doing EVA wire-work: extravehicular spacewalk sequences. As with the Emergency Air Lock and Brain Room scenes — only now a good thirty feet above the unforgiving concrete floor, with absolutely no latitude for error — the wirework was handled by Eugene's Flying Ballet and supervised by its leader, Eric Dunning, who'd been trained by Arthur Kirby, the man who'd first demonstrated the technique in a sensational London staging of "Peter Pan" in 1904. [Gallery: Making of '2001: A Space Odyssey']

Weston's audacious performances, which unfolded without a safety net, comprise some of the most physically and technically demanding scenes shot during the making of "2001: A Space Odyssey." Decades before digital effects, they constitute an extraordinary, largely unsung moment in film history. With the camera always positioned directly below him, Weston could rotate and maneuver freely on an x-axis. It was the only way to simulate weightlessness in a gravitationally bound studio environment, and the portrayal later won rave reviews for its realism from those who'd actually done it.

Dan Richter, fortunate to witness the scene, provided a vivid description in his 2002 book "Moonwatcher's Memoir: A Diary of '2001: A Space Odyssey'." "Passing through the door onto the great stage is like entering a cathedral," he wrote. "All around are vast curtains of black velvet. High above, hanging from invisible piano wires, stuntman Bill Weston, in a space suit, slowly turns like a modern angel in the black abyss . . . For a moment, I have trouble breathing. It is stunning. Stanley is in a huddle around the big 65-millimeter camera with Bryan Loftus, Peter Hannan, and other crew members."

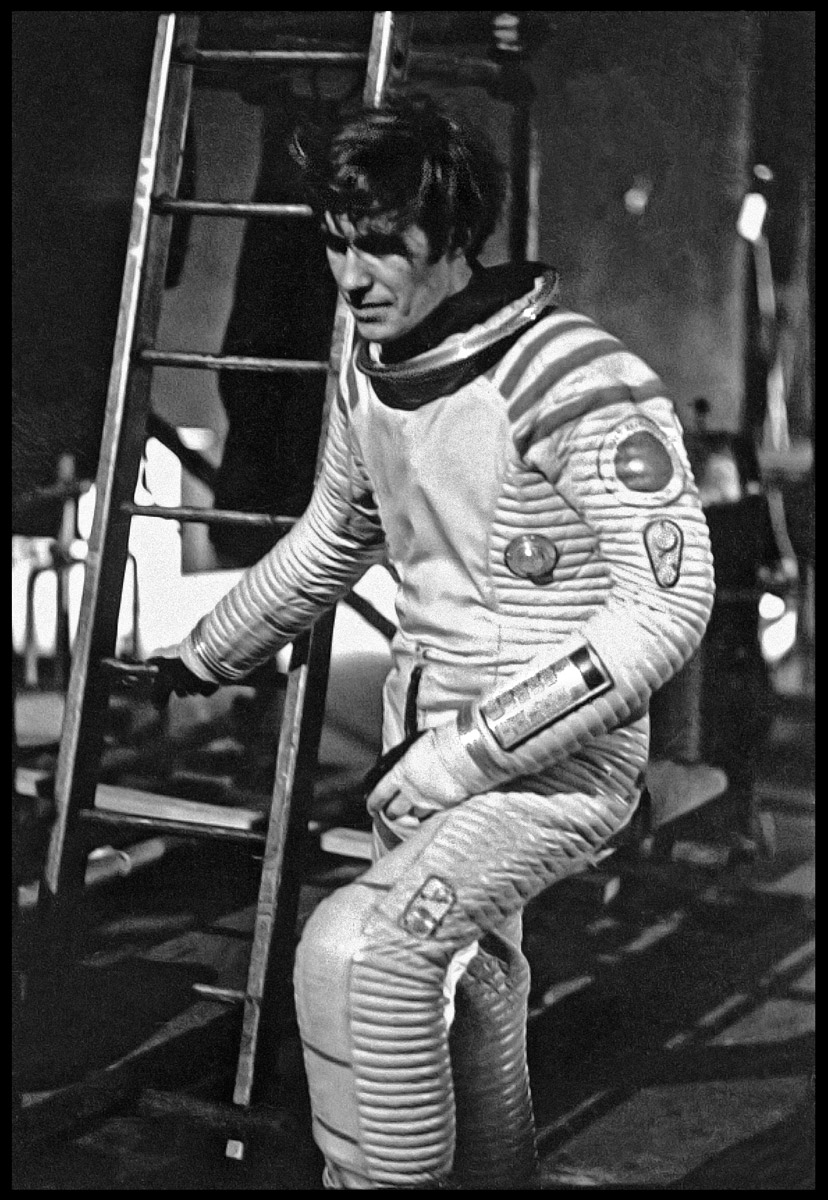

A square-jawed, striking presence who looked not unlike the young Clint Eastwood, Weston was over six feet tall and had been brought up in India under British colonialism. Then twenty-five, he'd become a stuntman after "some freelance soldiering in Africa." He'd done a number of films prior to "2001," but nothing remotely as ambitious as this. Prior to his space walks above Stage 4, he'd been outfitted with a salt-and-pepper wig and doubled for Keir Dullea in the emergency air lock scene. He'd also spent hours hanging at odd angles in the overheated HAL Brain Room for shots where Dullea's face didn't need to be visible through his helmet.

In his ceaseless drive for realism, Kubrick had turned down the suggestion that air holes be punched into the back of Weston's helmet. He was worried that light might leak through and be visible through the visor. When Weston countered by proposing that the air holes he was suggesting could be screened by black gauze, which should have taken care of any possible light leakage, Kubrick still refused. The director also insisted that Weston wear his Bowman wig in the sweaty, overheated environment of the suit—a directive the stuntman soon evaded by discreetly flipping the thing into a corner of his high launch platform. [Stanley Kubrick's Iconic '2001: A Space Odyssey' Sci-Fi Film Explained (Infographic)]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kubrick's intransigence meant Weston's space suit was hermetically sealed. While he did have a small tank of compressed air stashed in his backpack, it contained only ten minutes' worth—and this was unregulated, simply feeding into his helmet via a tube until empty. Given the complexity of the shots, and the amount of time it took simply to remove the platform used to prepare the stuntman's wires and suspend him, ten minutes wasn't enough. And there was another problem: even when the tank was feeding air into the suit, there was no place for the carbon dioxide Weston exhaled to go. So it simply built up inside, incrementally causing a heightened heart rate, rapid breathing, fatigue, clumsiness, and eventually, unconsciousness.

Though Kubrick and Cracknell could use megaphones to issue orders from below, there was no real communication between the stuntman and the ground. Weston had only those ten minutes of air siphoning into the helmet, with the exhaled carbon dioxide building up the whole time. In view of the perilous circumstances, he'd worked out his own way of mitigating the risks. When Weston started to get groggy from the CO2, "I was doing the alphabet backward, and as long as I could do it, I guessed I was okay." He'd arranged a signaling system with Dunning's wire man: if he extended his arms directly outward in a crucifix shape, he was near his limit and should be brought in very soon. If he did it twice, it was an emergency, and he needed to be recovered immediately.

It took almost five minutes to move his launch tower out of the shot and that much time to bring it back. Added to this, ever since Hannan's injury, Kubrick had checked the camera frame only from off to the side, "because he was still terrified of something dropping on him," remembered Weston. This, in turn, required that after the stuntman's release from his platform, and after the inevitable discussion down below, the camera still had to be moved back into position. All this took yet more time. With just ten minutes of air to mitigate the CO2 buildup in the first place, they were operating at the outer limits of Weston's endurance.

"The first time I went out, Kubrick was really sort of agitated because it had been explained to him that I had limited time," Weston recalled. With the tank almost empty and the air growing inexorably more poisonous, he recited the alphabet backward until he started to lose his thread. He gave himself another couple minutes and then with reality greying into a buzzing haze all around him, he extended his arms in the crucifix position. Illuminated by a powerful beam of light, rotating slowly in a black abyss, Richter's modern angel had become a floating, crucifed spaceman. Through the helmet, Weston heard "someone tacking up to Stanley and saying, 'We've got to get him back.'" He also heard Kubrick's response: "Damn it, we just started. Leave him up there! Leave him up there!" [One HAL of a Ship: 'Space Odyssey' Model Shows Astounding Detail]

By now, he was using his last ounces of strength to make repeated cruciform shapes with his arms. Then he blacked out. "They brought the tower in, and I went looking for Stanley," the ex-mercenary recalled. "I was going to shove MGM right up his . . ." He paused. "And the thing is, Stanley had left the studio and sent Victor [Lyndon, the associate producer] to talk to me." Kubrick didn't return to the studio for "two or three days," said Weston. "I certainly remember it as two or three days . . . I know he didn't come in the next day, and I'm sure it wasn't the day after. Because I was going to do him."

Lyndon arranged that Weston get "Elizabeth Taylor's dressing room, including a refrigerator with beer and stuff in it." He also got "the biggest coming up for R&R, and Stanley would pay for it"—that is, a large raise. By the time Lyndon judged Kubrick could safely return to the studio, all was forgiven. Even so, Weston commented decades later, "Stanley, if he got involved, it was pretty much an empire of destruction."

You can buy "Space Odyssey" on Amazon.com.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.