ESPRESSO Planet Hunter Ready to Drink in the Universe for Alien Worlds

A powerful new planet hunter has begun searching the heavens for rocky, potentially habitable worlds.

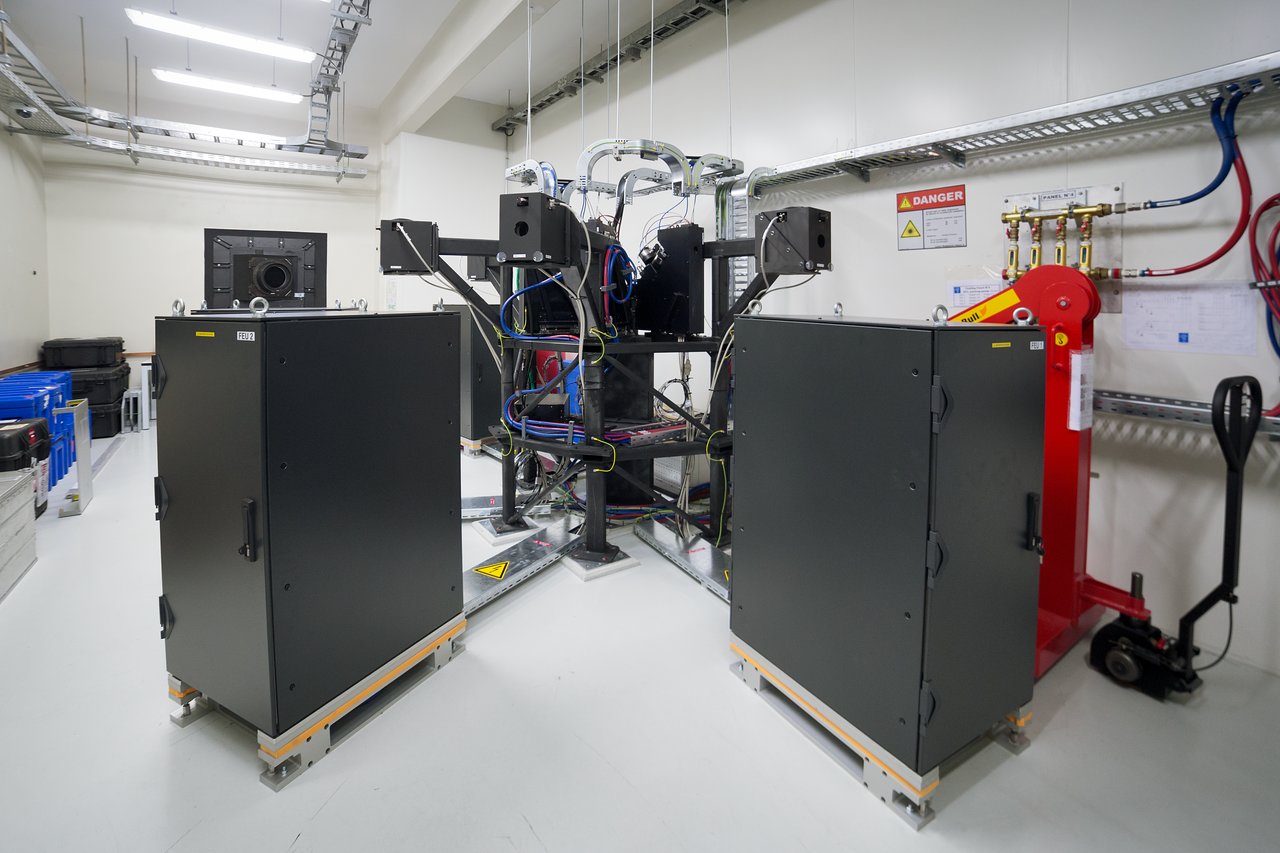

The ESPRESSO instrument, which is installed on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in northern Chile, made its first observations last month, project team members announced today (Dec. 6).

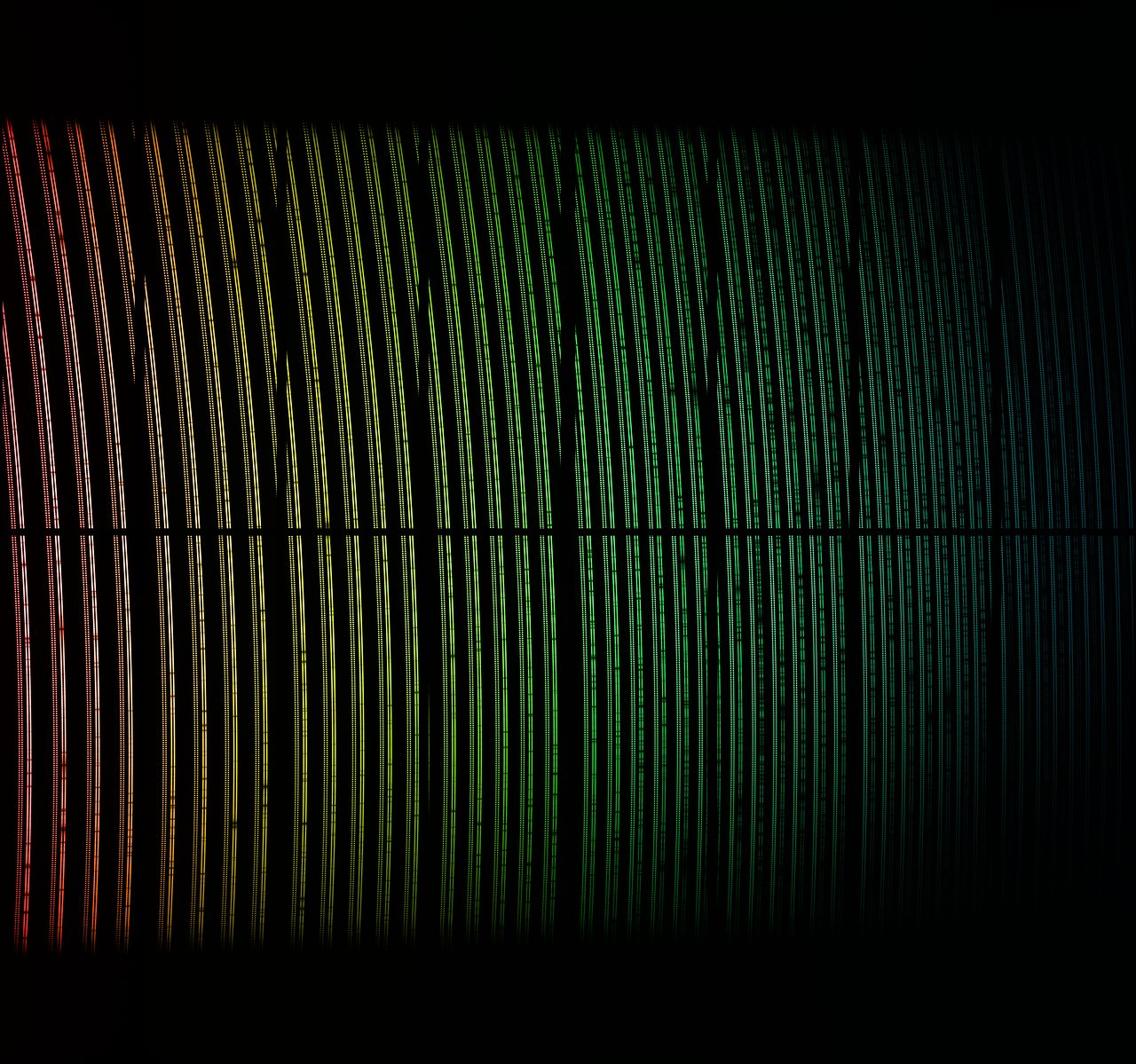

ESPRESSO is designed to find alien planets via the "radial velocity" method — that is, by detecting the tiny wobbles in a star's movement caused by the gravitational tug of orbiting planets. The instrument is the next-generation version of the prolific HARPS spectrograph, which has discovered more than 100 exoplanets to date. [7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets]

Only NASA's famous Kepler space telescope, which looks for the tiny brightness dips caused when planets cross their star's face, has found more alien worlds than HARPS. (The gap between the two is pretty big, however: Kepler's tally currently stands at 2,515 planets across its two missions, along with 2,500 or so additional "candidates" awaiting confirmation by follow-up studies or observations.)

"ESPRESSO isn't just the evolution of our previous instruments like HARPS, but it will be transformational, with its higher resolution and higher precision," project lead scientist Francesco Pepe, of the University of Geneva in Switzerland, said in a statement.

Just how precise will ESPRESSO (whose name is short for Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet and Stable Spectroscopic Observations) actually be? Project team members are aiming for a velocity-measurement precision of just a few centimeters (1 inch or so) per second, compared with the 1 meter (3.3. feet) per second capability of HARPS. ESPRESSO should therefore be able to spot some of the smallest planets ever found, ESO representatives said.

Part of the improvement is due to technology advances, and part owes to ESPRESSO's placement on a much larger telescope, team members said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

HARPS sits on an 11.8-foot (3.6 m) scope at ESO's La Silla Observatory, which is also in Chile. The VLT consists of four 26.9-foot-wide (8.2 m) "unit telescopes" — and ESPRESSO will be linked to all of them, achieving the light-collecting equivalent of a single 52.5-foot-wide (16 m) scope, ESO representatives said.

"This success is the result of the work of many people over 10 years," Pepe said. "ESPRESSO will be unsurpassed for at least a decade. Now I am just impatient to find our first rocky planet!"

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.