Early Moon Photos Revealed More Than Was Known

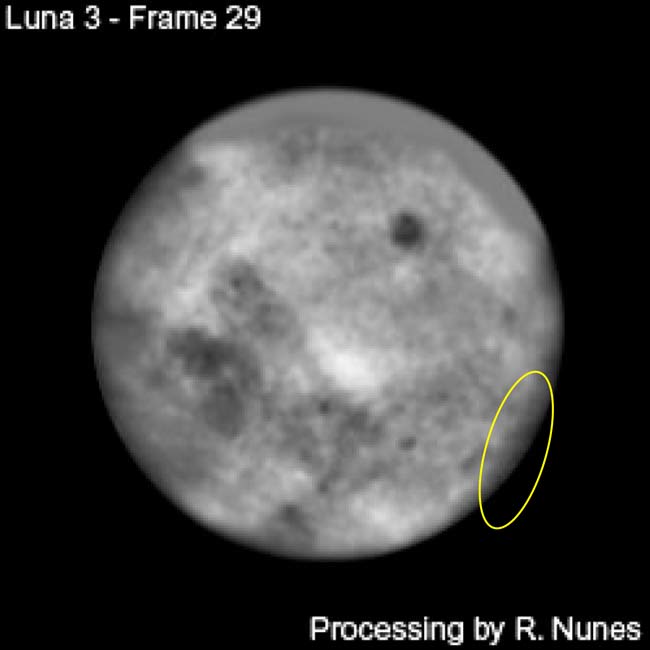

Newly reprocessed images of the Moon's far side taken by Soviet spacecraft more than 40 years ago may have confirmed that the Moon's biggest impact scar was glimpsed far earlier than previously thought.

The images were acquired by the Luna 3 and Zond 3 spacecraft in October 1959 and July 1965 respectively and provided the first look at the Moon's forever hidden far side.

The original murky and noisy images have now been re-processed by amateur astronomer Ricardo Nunes and add weight to a proposal by V.V. Shevchenko and V.I.Chikmachev of the Sternberg State Astronomical Institute in Moscow that a dark smudge visible on the Moon's limb in Luna 3 images is part of the western edge of the enormous South Pole-Aitken Basin (SPAB).

Gargantuan basin

The SPAB is a gargantuan impact basin-1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers) diameter-that sprawls between the lunar South Pole and the crater Aitken. The basin is 8 miles (12 kilometers) deep.

Despite its size, over subsequent years only slivers of the basin were seen in images and it took until 1992 for the SPAB to be seen in its entirety; courtesy of the Galileo spacecraft while en-route to Jupiter.

Further image processing work by Nunes on images captured by Zond 3 reveal the eastern portion of the SPAB's mountainous outer rings. Those now-eroded peaks were thrust up 4.1 billion years ago, and the yawning basin they encircle is an important tool for looking deep into lunar history.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The formation of SPAB was a huge event in early lunar history, and its influence was likely felt all across the Moon," said Lisa Gaddis of the Astrogeology Program at the U.S. Geological Survey. "Not only is SPAB the biggest 'hole' in our solar system, but it must have dug down deeply enough to expose and excavate materials from deep within the Moon."

The Moon's mantle is the region buried more than 62 miles (100 kilometers) below the impact-pummelled outer crust, and only the most powerful impacts can liberate the well concealed mantle material. It is still hotly debated how much mantle material resides within the basin, although high levels of the iron and thorium-thought to be abundant in the mantle-are present.

Moon rocks

The Apollo missions returned 842 pounds (382 kilograms) of Moon rock, but none of it was from the mantle.

Scientists would love to study this well-guarded material "It would tell us a lot about what exists at depth within the Moon," Gaddis says. "It would also help us to understand how a large impact event behaves, when the event occurred, how much material might have been thrown out, how much melted and the composition of the mantle or lower crust."

The SPAB may also harbor some far-flung samples, as Gaddis explains: "Although it's generally believed that most material currently seen within SPAB is derived locally, there may be small amounts of 'foreign' materials in SPAB from other, younger impacts on the Moon. So it's possible that we'd find compositions that have not yet been sampled on the Moon. We'd also learn something about the early history of the Earth/Moon system and how it formed."

Theorists say the Moon was carved from Earth in a spectacular collision by a Mars-sized object.

Far-side exploration

Researchers now understand the importance of the SPAB, but had the basin been seen fully in those first far side images, lunar exploration may have steered a different course.

"It would likely have changed lunar maps and our understanding of the occurrence and distribution of large impacts on terrestrial planets. It also might have influenced exploration or at least imaging of the far side at an earlier time," Gaddis said.

The next time we lay eyes on the SPAB may well be courtesy of NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) to be launched in 2008. LRO is bristling with instrumentation and will provide our best look at the SPAB, nearly 50 years after it was stumbled upon by Luna 3.

- Top 10 Apollo Hoax Theories

- Moon Shots: The Best of Your Amazing Images

- Top 10 Cool Moon Facts

David Powell is a space reporter and Space.com contributor from 2006 to 2008, covering a wide range of astronomy and space exploration topics. Powell's Space.com coveage range from the death dive of NASA's Cassini spacecraft into Saturn to space debris and lunar exploration.