Pluto Flyby Anniversary: The Most Amazing Photos from NASA's New Horizons

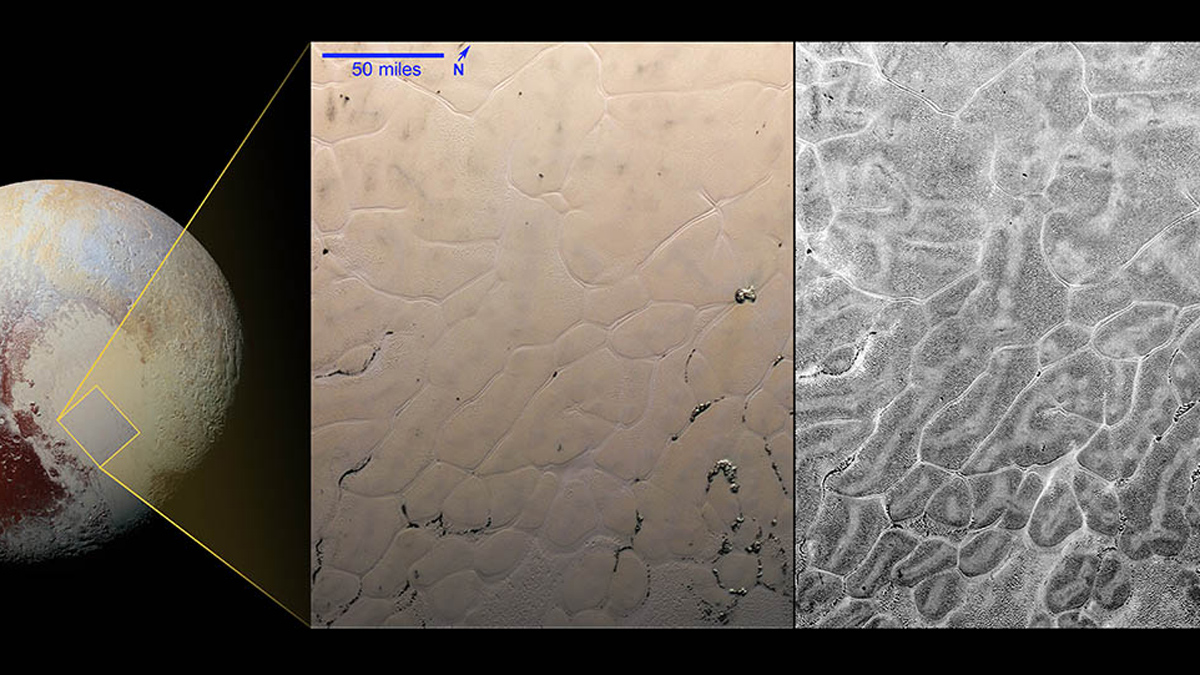

Sputnik Planum

Scientists on NASA’s New Horizons mission have processed images of Sputnik Planum — the western half of Pluto's "heart" — to reveal intricate, never-before-seen patterns in the surface textures of these vast glacial plains. The left inset on the image shows an enhanced-color close-up of a region of cellular plains in the middle of Sputnik. The right-hand inset is a "scattering map" of the same region, created by combining two images of Sputnik Planum taken at two very different viewing angles as New Horizons spacecraft flew past. The scattering map reveals that the centers of cells tend to be smoother, while their edges tend to be rougher and more pitted. The boundaries between ice cells in many cases tend to be even brighter and hence smoother than the cell centers. This pattern is very likely a consequence of the convective flow that New Horizons scientists think is taking place within the nitrogen ice of Sputnik Planum, where warmer ice rises at the centers of cells, travels outward, and descends at the edges, like a cosmic lava lamp.

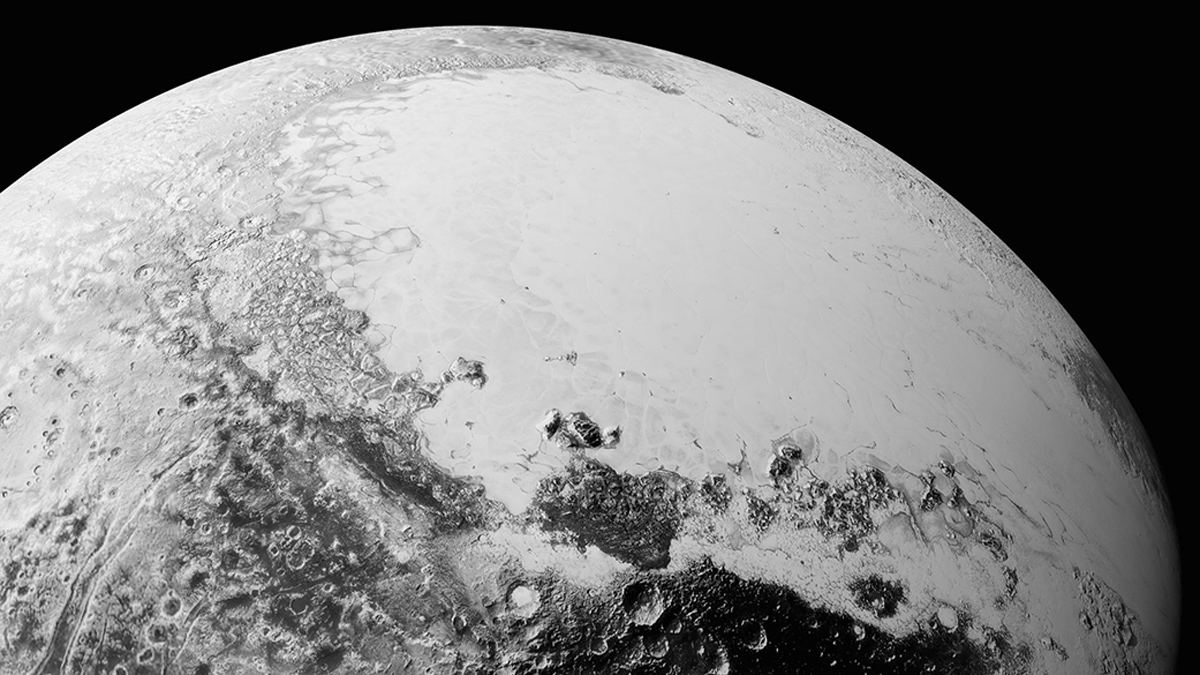

Spherical Mosaic

This synthetic perspective view of Pluto shows what you would see if you were approximately 1,100 miles (1,800 kilometers) above Pluto’s equatorial area, looking northeast over the dark, cratered, informally named Cthulhu Regio toward the bright, smooth, expanse of icy plains known as Sputnik Planum. The entire expanse of terrain seen in this image is 1,100 miles (1,800 km) across. The images were taken as New Horizons flew past Pluto on July 14, 2015, from a distance of 50,000 miles (80,000 km).

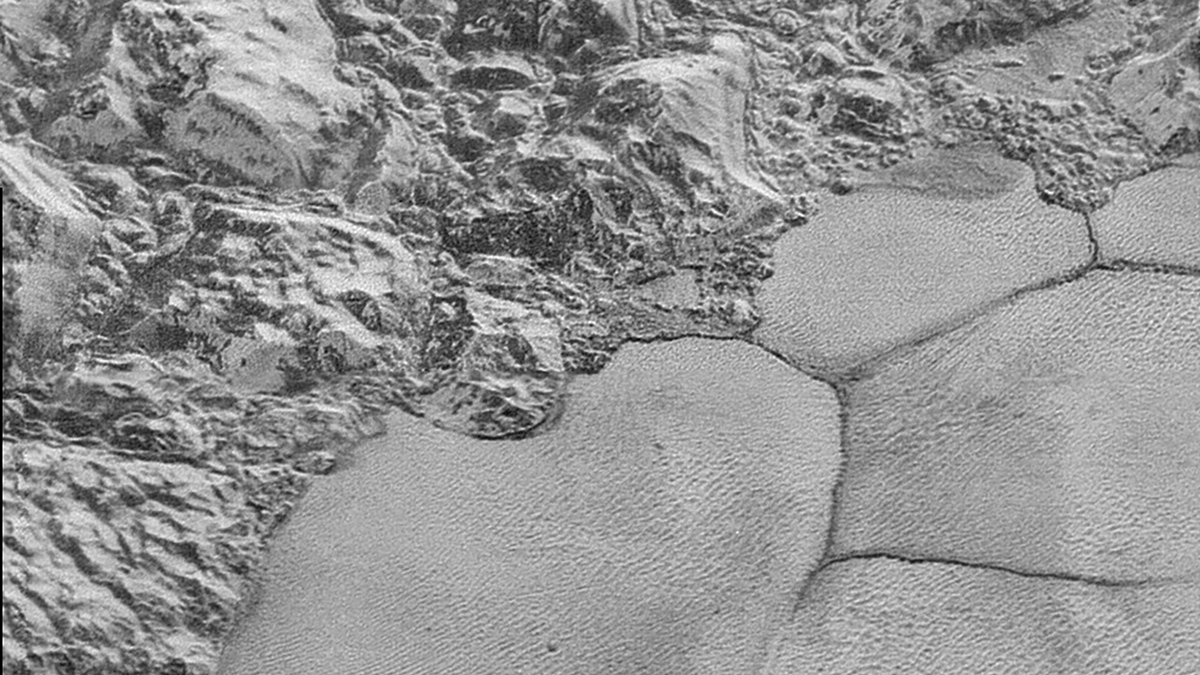

al-Idrisi Mountains

In this high-resolution image from NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, great blocks of Pluto’s water-ice crust appear jammed together in the informally named al-Idrisi mountains. Some mountainsides appear coated in dark material, while other sides are bright. Several sheer faces appear to show crustal layering, perhaps related to the layers seen in some of Pluto’s crater walls. Other materials appear crushed between the mountains, as if these great blocks of water ice, some standing as much as 1.5 miles high, were jostled back and forth. The mountains end abruptly at the shoreline of Sputnik Planum, where soft, nitrogen-rich ices form a nearly level surface, broken only by the fine trace work of striking, cellular boundaries and the textured surface of the plain’s ices (which is possibly related to sunlight-driven ice sublimation).

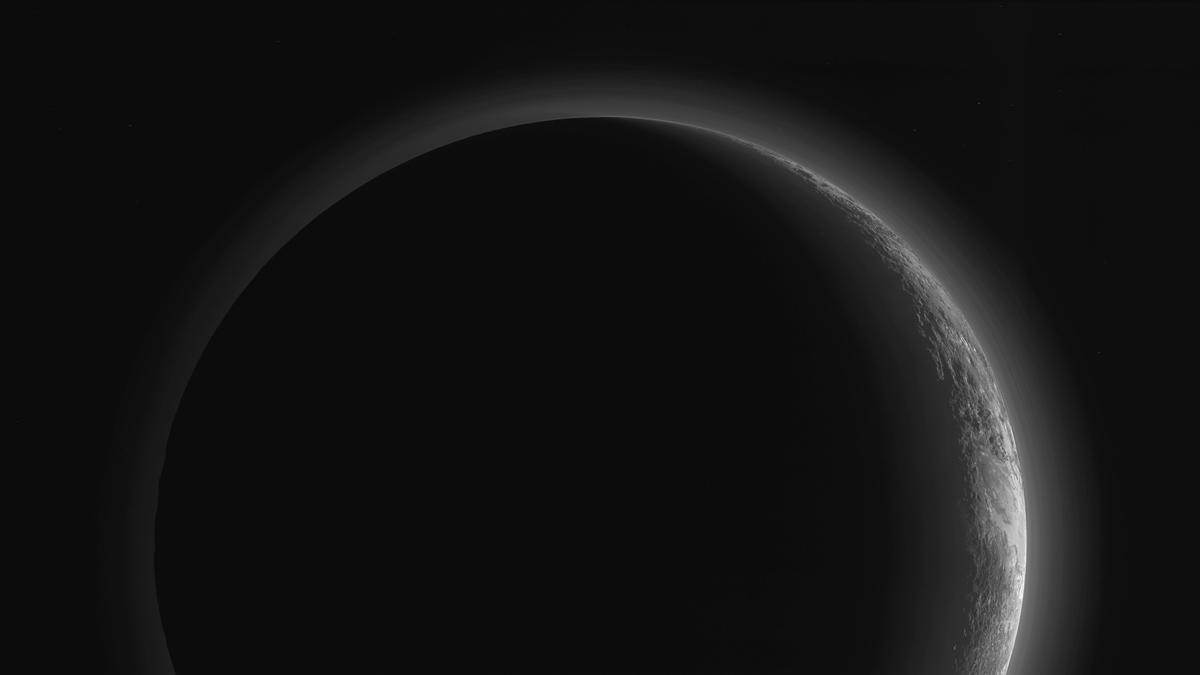

Stunning Crescent

This image of a crescent Pluto was made just 15 minutes after New Horizons’ closest approach to the dwarf planet on July 14, 2015, as the spacecraft looked back at Pluto toward the sun. The wide-angle perspective of this view shows the deep haze layers of Pluto's atmosphere extending all the way around Pluto, revealing the silhouetted profiles of rugged plateaus on the night (left) side. The shadow of Pluto cast on its atmospheric hazes can also be seen at the uppermost part of the disk. On the sunlit side of Pluto (right), the smooth expanse of the informally named icy plain Sputnik Planum is flanked to the west (above, in this orientation) by rugged mountains up to 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) high. The backlighting highlights more than a dozen high-altitude layers of haze in Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere. The horizontal streaks in the sky beyond Pluto are stars, smeared out by the motion of the camera as it tracked Pluto.

Closest Approach So Far

Guests and New Horizons team members count down to the spacecraft's closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015 at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

The Next Stop

New Horizons did not just stop or shut down after its historic Pluto flyby. Instead, the spacecraft kept streaking outward into the Kuiper Belt, a region of icy objects at the fringe of our solar system.

And that's where New Horizons will find its next target. The spacecraft has a date with the Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69. On Jan. 1, 2019, New Horizons will fly by the icy object and give astronomers their first glimpse at what such objects really look like.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.