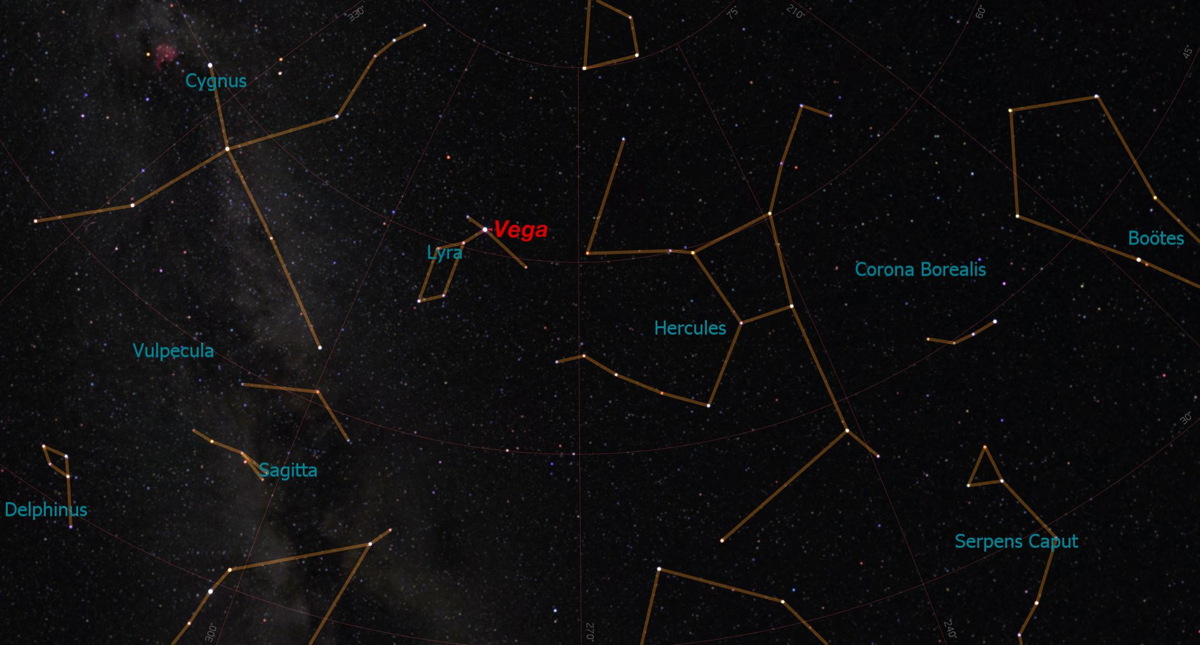

Vega Shines Overhead in Lyra Constellation This Week

In the evening hours approaching midnight, Northern Hemisphere skywatchers will be able to spot the brilliant bluish-white star Vega (pronounced VEE'-guh, not VAY'-guh, unlike the car model from the '70s) as it shines nearly overhead this week.

Vega, located just 25 light-years away, belongs to the constellation Lyra, the lyre. At magnitude 0.03, it is the third-brightest star that most U.S. observers get to see, outshone only by Arcturus (now in the western sky, at magnitude minus 0.05) and Sirius (magnitude minus 1.44). (Lower magnitudes denote brighter light sources.)

Because both Vega and Arcturus are in our early summer evening sky, try to see if you can detect a difference in their brightness levels. They are separated by less than one-tenth of a magnitude; that alone will make it difficult. And the fact that Vega is "an electric, steely blue that shines steady and cold in contrast to golden Arcturus," as Peter Lum put it in his book "The Stars in Our Heaven," (Pantheon Books, 1948), doesn't make it any easier, as you'd have to compare the brightness of two different colors. [Night Sky: Visible Planets, Moon Phases & Events, July 2017]

Say "cheese"

On July 17, 1850 — 167 years ago — Vega became the first star (other than the sun) to be photographed, when it was imaged by William Bond and John Adams Whipple at the Harvard College Observatory. Using the daguerreotype photograph-producing process of the day, it took an exposure of 100 seconds to capture an image of Vega.

Planet nursery?

In January 2005, astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, announced that features observed in a cloud of dust swirling around Vega may be the signatures of an unseen planet in an eccentric orbit around the star. In Earth's solar system, dust particles created by asteroid collisions and the evaporation of comets spiral in toward the sun. The gravity of the planets affects the distribution of these dust particles. Observations of Vega with the Infrared Astronomy Satellite in 1983 provided the first evidence for a href="https://www.space.com/9662-wallpaper-27.html">large dust particles around another star, possibly debris related to the formation of planets. This discovery likely inspired Carl Sagan to place an alien listening post at Vega in his novel "Contact."

So much to see

Lyra is also a rich repository for observers with amateur telescopes. Two fainter stars form a small triangle with Vega; one of these also joins three others in a parallelogram, a rather uninspiring star pattern. However, you should try to locate Epsilon Lyrae, the other faint star in the Lyra triangle. Here lies much more than meets all but the sharpest eye. Appearing to the average eye as a single star, it may be seen as a very close double by those with exceptional vision — the two stars are separated by just over one-tenth of the apparent diameter of the full moon. Through binoculars, Epsilon Lyrae easily splits into two stars. But then, using a 3-inch (7.6 centimeters) or larger telescope reveals that these two stars are themselves both doubles! That makes four stars for Epsilon Lyrae, better known as the "Double-Double" star in Lyra.

The star Sheliak is one of the two stars that form the southern side of the parallelogram and appears to diminish by half of its normal brightness about every 13 days, when it's eclipsed by a darker companion star.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Between this winking star and its neighbor, Sulafat, is the famous Ring Nebula, Messier 57. Visible in small telescopes as a tiny oval patch of dim light, it is the gaseous shell puffed out from a dying star, which is evolving to become a white dwarf. Millions of years ago, this star exploded, hurling out great masses of gas. We see the star now through the thin part of this gaseous envelope.

And when you look at Lyra tonight or later this week, ponder the fact that you're looking in the general direction toward which our solar system is traveling in space, sometimes referred to as the "apex of the sun's way." Most of the stars that surround Lyra have proper motions that carry them away from Vega's vicinity; this "spreading apart" effect is an illusion of perspective, akin to the way telephone poles ahead of us appear to move apart as we drive along a road. In fact, we're moving toward Vega at 12 miles per second (19 kilometers per second), and we'd either come pretty close to it, or possibly even collide with it, in about 500,000 years. But thankfully, this will not happen, since Vega itself is moving, too! [Best Telescopes for the Money - 2017 Reviews and Guide]

A "punny" conclusion

Many star books refer to Lyra as a harp. But that's not quite the case. In terms of size, a small harp can be played on a person's lap, whereas larger harps (like the one that was used by the late Harpo Marx) are quite heavy and must rest on the floor.

But Lyra represents a lyre (pronounced like "liar"), which is quite a different instrument entirely. A classical lyre has a hollow body constructed out of turtle shell, which served as a sound-chest or resonator. To play a lyre, people would not strum the strings with their fingers as they would with a harp but rather play it like a guitar or ukulele, with a pick (called a plectrum).

Many hundreds of years ago, if a young man were courting a young lady, he might take her to a dark, quiet and serene setting, and as she gazed upward at the starry firmament, he would entertain her by playing his lyre.

Many years ago, Dr. Fred Hess, a very popular lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium, would tell his audience that this romantic tradition actually continues to this very day, but without the instrument. "On any given summer night, a young man might take his girlfriend to a beach or parking lot," he would say. "And as she stared up and looked into the starry night sky, in all likelihood, she too was probably listening to a liar."

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.