In First, Einstein Relativity Experiment Used to Measure a Star's Mass

The mass of Stein 2051 B, a white dwarf star located about 18 light-years from Earth, has been a subject of some controversy for over a century. Now, a group of astronomers has finally made a precise measurement of the star's mass and settled a 100-year-old debate, using a cosmic phenomenon first predicted by Albert Einstein.

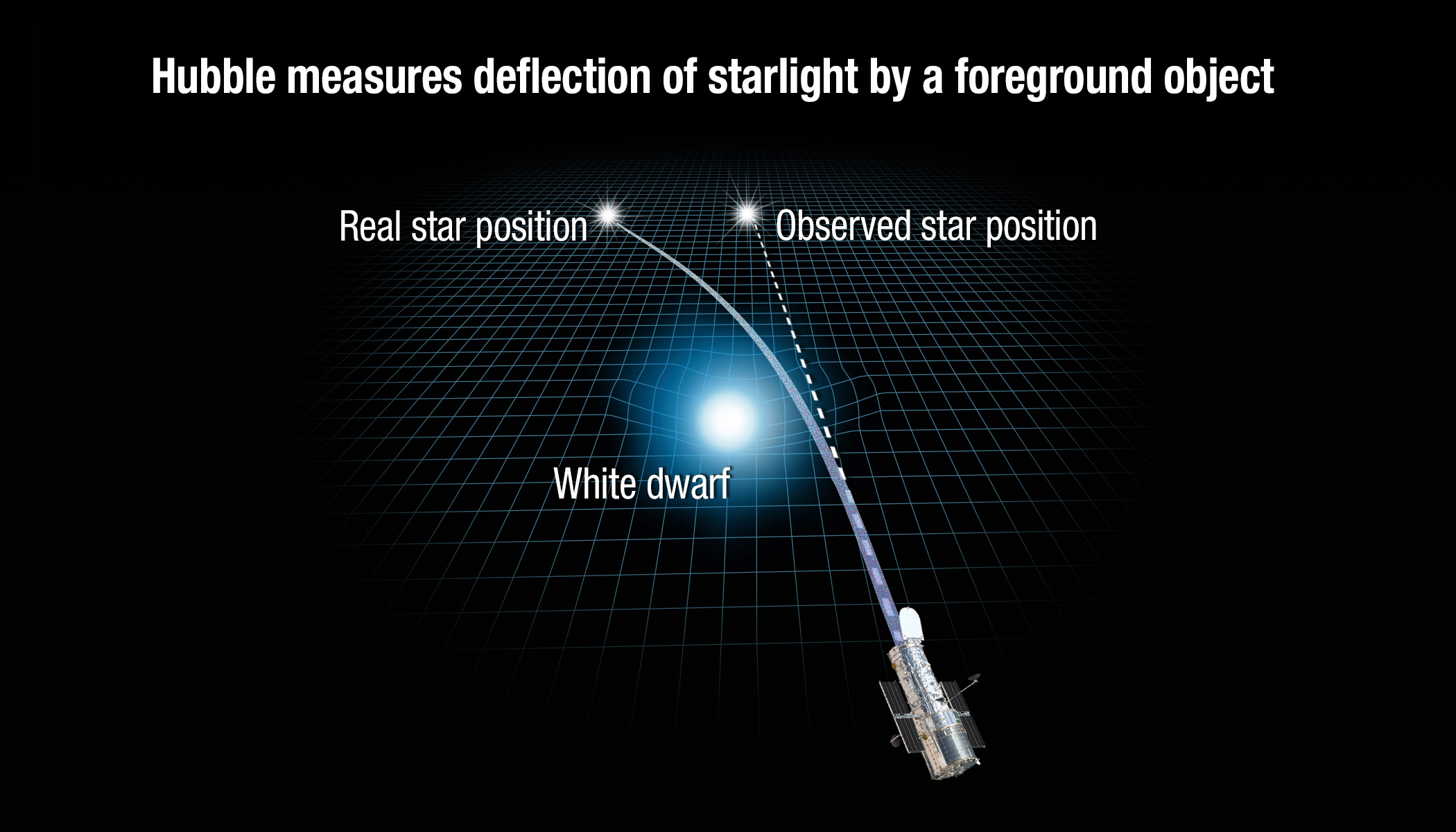

The researchers calculated the star's mass using carefully timed observations made by the Hubble Space Telescope, which studied Stein 2051 B when it eclipsed another, more distant star, as seen from Earth. During this transit, the background star appeared to change its position in the sky, moving ever so slightly to the side, even though its actual position on the sky had not changed at all.

This cosmic optical illusion is broadly known as gravitational lensing, and its effects have been observed extensively throughout the universe, especially near very massive objects, such as entire galaxies. The effect occurs because a massive object warps the space around it and acts like a very large lens, bending the path of the light from the more distant object. In some cases, this creates the illusion that the background star has been displaced. [Einstein's Theory of Relativity Explained (Infographic)]

(Water can also create this kind of displacement illusion; try placing a pencil in a glass of water, and note that the submerged half of the pencil appears disconnected from the dry half.)

Einstein predicted that these displacement events could be used to measure individual stellar masses. That's because the extent to which the background star's position is offset depends on the mass of the foreground star. But telescopes at the time lacked the sensitivity to make that dream a reality.

The scientists behind the new work said no one, before now, has ever used the displacement of a background star to calculate the mass of an individual star. In fact, there is only one other example of scientists measuring this displacement between individual stars: During the 1919 total solar eclipse, scientists saw the sun displace a few background stars. That measurement was possible only because of the sun's proximity to Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A paper describing the new work was published online today in the journal Science.

A cosmic lens

Einstein's theory of general relativity hypothesized that space is flexible rather than fixed, and that massive objects (like stars) create curves in space, sort of like a bowling ball creating a curve on the surface of a mattress. The degree to which an object warps space-time depends on how massive that object is (similarly, a heavier bowling ball puts a deeper imprint on a mattress).

A ray of light normally travels in a straight line through empty space, but if the ray passes close by a massive object, the curve in space created by the star acts like a bend in the road, causing the light ray to veer away from its formerly straight path.

Einstein showed that this deflection could direct more light toward the observer, similar to how a magnifying glass can focus diffuse light from the sun down into a single spot. This effect causes the background object to appear brighter, or it creates a ring of bright light around the foreground object called an Einstein ring.

Astronomers have observed Einstein rings and "brightening events" when very massive foreground lenses, like entire galaxies, create the phenomena. These have also been observed along the plane of the Milky Way galaxy, where individual stars likely cause the lensing effect. It has also been used to detect planets around other stars.

In the new study, astronomers reported the first ever observation of so-called "asymmetric lensing" involving two stars outside Earth's solar system, in which the position of the background star appeared to change.

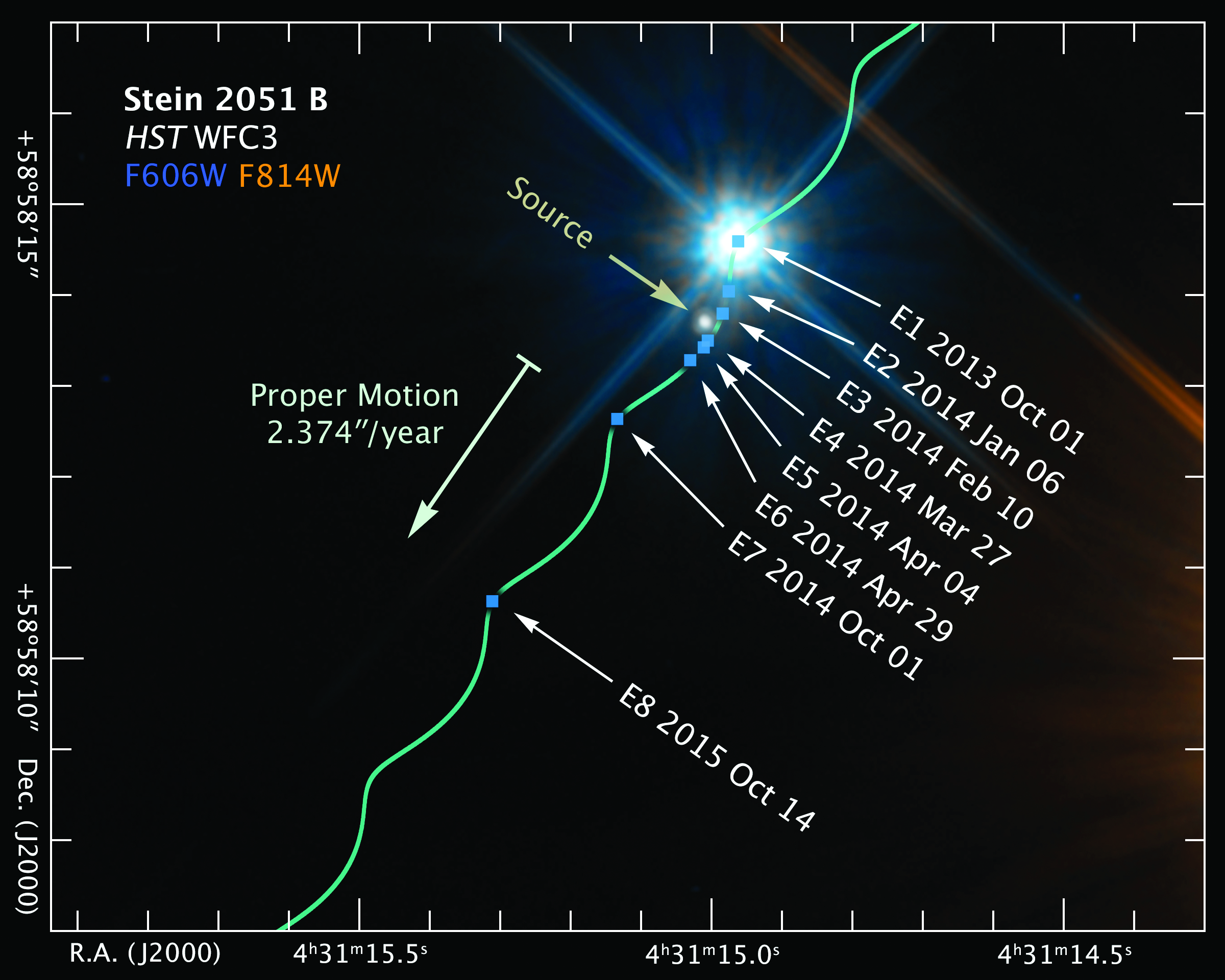

The degree of displacement is directly related to the foreground object's mass. With relatively "light" objects, like stars, the displacement is extremely small and thus more difficult to detect, according to Kailash C. Sahu, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, and the lead author on the new paper. In the case of Stein 2051 B, the displacement was about 2 milliarcseconds on the plane of the sky, or about equal to the width of a quarter seen from 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) away, Sahu said.

Measuring such a subtle change required a powerful instrument, like the Hubble telescope's high-resolution camera, which was installed in 2009. This instrument also made it possible to pick out the light from the displaced star, which was somewhat overshadowed by the light from Stein 2051 B — like a firefly next to a lightbulb, Sahu said.

The researchers took eight measurements between October 2013 and October 2015, so they could observe the white dwarf moving across the sky, eclipsing the background star and creating the displacement. The scientists also observed the actual position of the background star after the white dwarf had passed by.

Many variables could affect whether scientists can observe more events like this. Those variables include the alignment of the two objects, the mass and proximity of the foreground object, the separation between the foreground and background object, and the sensitivity of the telescope. But Sahu said he thinks his team has demonstrated the effectiveness of the method and that scientists could use it to measure the masses of about two to four nearby stars per year.

Star fossils

White dwarfs are stars that have stopped burning hydrogen in their cores and subsequently shed their outer layers. In each of these stars, the remaining mas has collapsed into a dense core known as a white dwarf. This collapse drives up the temperature on the surface of these objects, so they may burn hotter than "living" stars.

"At least 97 percent of the stars in the sky, including the sun, will become or already are white dwarfs," Terry Oswalt, a professor of engineering and physics at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida, wrote in an accompanying Perspectives article in Science. "Because they are the fossils of all prior generations of stars, white dwarfs are key to sorting out the history and evolution of galaxies such as our own."

The mass of Stein 2051 B has been "a source of controversy for over 100 years," said Oswalt, who was not affiliated with the new research.

The current picture that scientists have of white dwarfs suggests that the mass and radius of these objects reveals important information about how they formed, what they're made of, and what kind of stars they formed from, according to Sahu.

Previous measurements of the mass of Stein 2051 B suggested it was largely composed of iron, but that finding presented several problems based on accepted theories about white dwarf formation and stellar evolution, according to the research paper. For example, to form large amounts of iron, the star that would become Stein 2051 B would have to have been extremely massive, but the radius of Stein 2051 B suggests it formed from a star not much larger than the sun.

If those measurements of Stein 2051's mass were correct, it would have sent astrophysicists back to the drawing board to figure out how such an object could have formed. Sahu said astronomers realized their measurements of Stein 2051 B's mass were probably incorrect, but they had no way to know for sure.

Typically, the only way to measure the mass of a star is to observe how it interacts with another massive body. For example, in a binary system where two stars orbit each other, the heavier star will have a large influence on the motion of the lighter one, and by observing the two stars' interaction over time, scientists can calculate more and more specific values for the stars' masses. Stein 2051 B has a companion, but the two bodies orbit very far apart, so their influence on each other is minimal.

The new result shows that Stein 2051 B is in fact a very normal white dwarf, and it fits in just fine with the accepted formation theory Sahu said. Its mass is about 0.68 times the mass of the sun, indicating it formed from a star about 2.3 times the mass of the sun, Sahu said. That's compared to the previous measurement which placed the white dwarf's mass at about 0.5 times the mass of the sun. Not very many white dwarfs have had both their masses and radii measured precisely, he added .

"It confirms white dwarf mass-radius relationship," he said. "[Astrophysicists] have been using that theory, and it's good to know it's on solid footing."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter