Notes from Mars 160: Making Field Sketches During an EVA

The Mars Society is conducting the ambitious two-phase Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analog mission to study how seven crewmembers could live, work and perform science on a true mission to Mars. Mars 160 crewmember Annalea Beattie is chronicling the mission, which will spend 80 days at the Mars Desert Research Station in southern Utah desert before venturing far north to Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station on Devon Island, Canada in summer 2017. Here's her fifth dispatch from the mission:

Anyone who knows me knows I am not famed geologist Grove Karl Gilbert. In fact, I can't remember the last time I drew in the landscape for any reason. In terms of art-making, it never was, and still is not, an interest for me.

But I am always thinking about the role that the techniques and strategies of art will have in the long-term growth of small micro-societies living in extreme adversity in space. [See more Mars 160 photos here, and get daily images by the Mars 160 crew]

Here, at the Mars Desert Research Station, I've designed some art-based research to explore how observation in the field is a primary means of obtaining scientific knowledge for planetary field science. This series of drawing experiments focuses on the deliberate practice of geological field sketching in simulation. In particular, I'm thinking about whether field sketching improves the gathering of data in the field.

In a comparative study in two different kinds of deserts (one hot, dry desert and one polar desert) conducted between the Mars Desert Research Station here in Utah and Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station on Devon Island in Canada, the scientist/researcher is challenged to extend tools, methods, resources and protocols of geological field drawing in ways that may be useful for conducting planetary field science in an extreme environment like Mars. For our twin Mars 160 mission, field drawing tests in phase one will inform and conceptually deepen a parallel series of experiments in phase two.

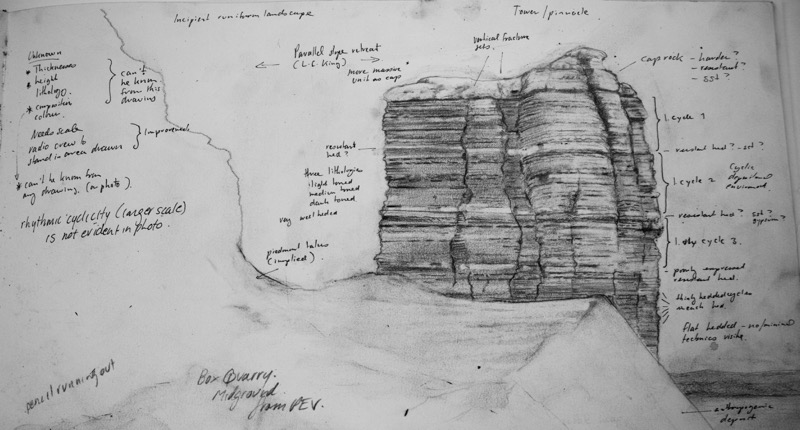

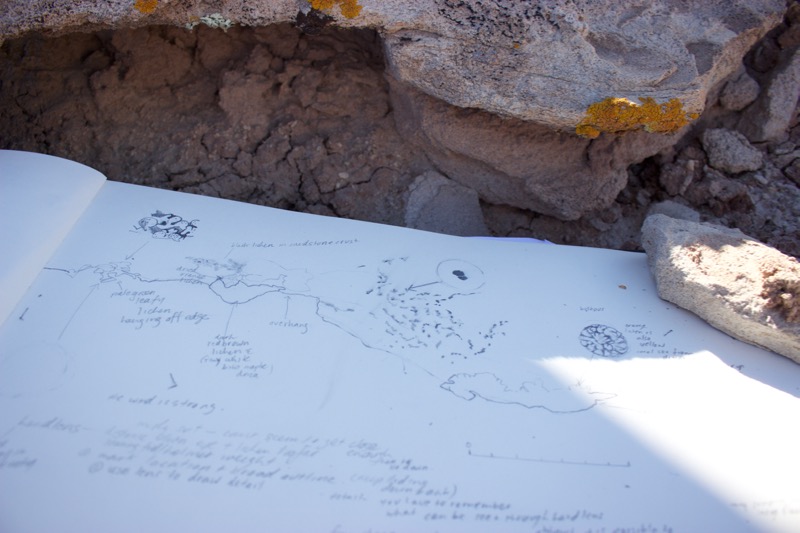

So far I've begun to test out how drawing in the spacesuit functions in terms of time constraints for the EVA (extravehicular activity) and tools (drawing tools like electric erasers and geological tools such as the hand lens, pictured above). And I've used my field sketches as blind data to see what a geologist can discover from the sketch without any prior knowledge of the subject drawn, both singly and in comparison with photos.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And always in my heart, I think about how the immersive experience of art affects us.

Today I was part of a team on a science EVA to Box Canyon Quarry. The science goal was to sample gypsum found in the high steep cliffs, from the veins of the pinstriped Summerville, in the crack fills and the nodules of the powdery greenish-white slopes of the Tidwell and in the crystals that grow in the sediment in depositions of both of these geological formations. As Mars 160 team member Jon Clarke, a geologist, says, "This is a very rich site for Mars analog research and is an excellent Mars analog with respect to geomorphology. Both canyons, large and small, are common on Mars, as are evaporites."

To reach Box Canyon, we drove to the lower Pinto Hills in the PEV (Pressurized Exploration Vehicle), aka the Ford Explorer. My role on this EVA was to act as the RoverCom by staying in the vehicle. This meant Jon Clarke and biologist Anushree Srivastava could safely leave the vehicle in full simulation to do sampling while I maintained the radio and a safe base in the PEV.

This gave me an opportunity to try to draw an outcrop of the cliffs from the PEV.

Jon Clarke suggests that on Mars, one mode of operation on an EVA might be that several astronauts are on the surface while one remains or returns to the rover to take notes and map the area with a sketch.

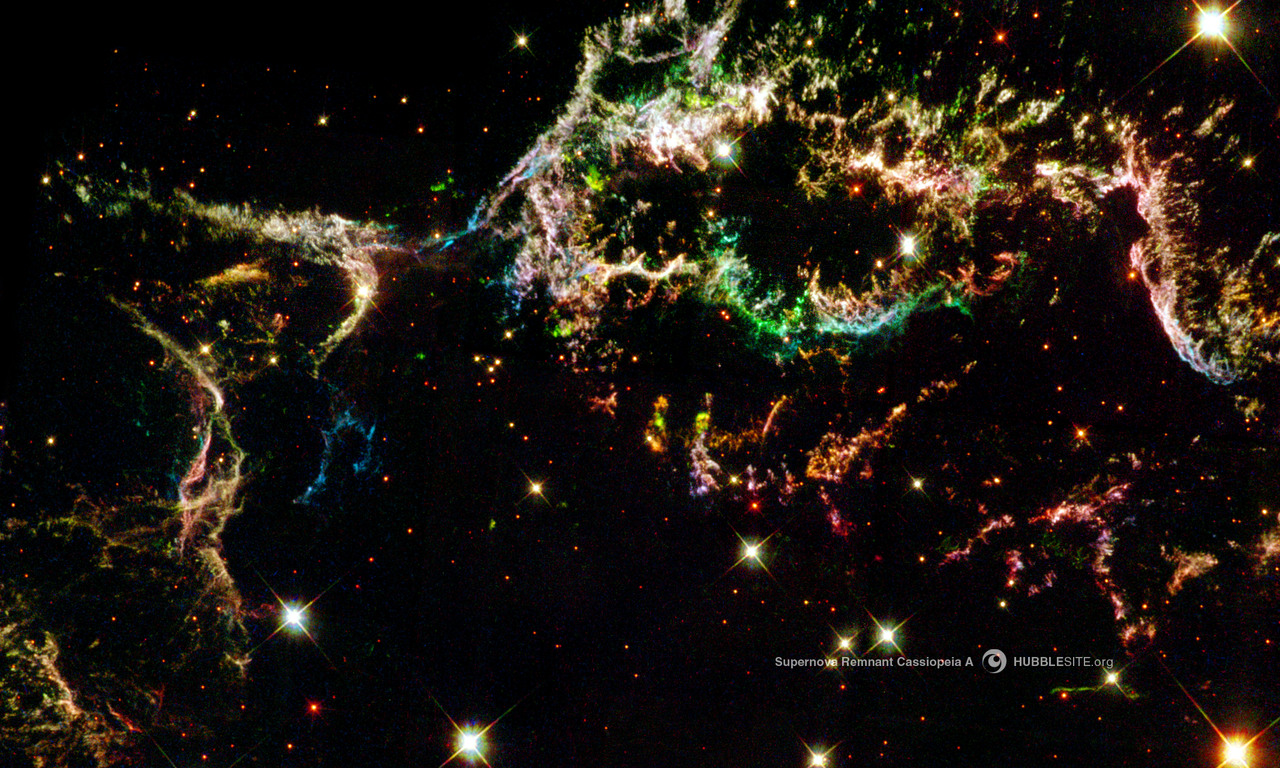

As I watched the others sampling at the base of the cliff, I ate a bit of early lunch from our lunch box and thought about the atmosphere on the surface of Mars. How will we understand our position in the landscape through the screens of spacesuits? [Spacesuit Suite: Evolution of Cosmic Clothes (Infographic)]

What will the light be like on Mars? What kind of shields will be used on the pressurized vehicles that travel across its terrain? Will the windows of the PEV be strongly tinted, and how will vision be affected? What does this mean for geological field drawing inside the vehicle?

Windows on pressurized vehicles won't give full protection from the cosmic radiation on Mars, but like here on Earth, ultraviolet rays are absorbed by glass and polycarbonates.

Shields on Martian vehicles will be used to keep out other types of radiation — for example, low-level cosmic rays, which are there all the time, and the particles from solar storms, which are predictable so we can plan ahead. Compared to deep space, the planet Mars itself will protect us by half and the Martian atmosphere, though thin, will also give some defense. On Mars, we can presume visibility through the windscreen will be at least as clear as it is through the tint in the windows of our PEV.

(By the way, for engineering reasons, the windows on PEVs on Mars will have to be smaller because of the internal atmospheric pressure on the hull. Windows are a weak point structurally, and I know engineers who would like to omit them from space vehicles altogether).

We can take it as a given for geological field drawing on the surface of Mars that wearing the spacesuit will change the way we use tools, processes and techniques that relate to drawing. For instance, I notice how, without the suit, when I erase something from the paper, I immediately blow away the shavings of the eraser with my breath without touching the drawing. In comparison, when drawing in the space suit, I brush away shavings from the paper with gloves, sometimes smudging the drawing.

Because the spacesuit prioritizes vision, we must adapt.

Here, in the back seat of the PEV, I'm thinking that the provocations of geological field sketching are not all necessarily related to technique or what can be done or not done within the physicality of the suit.

It's good to know what you are dealing with. When drawing, there is a virtual or abstract dimension in perception that is always dynamic. We bring our experiences and our prior patterns of sensorimotor perception to the context of the drawing, as part of our lived relation to the subject of drawing.

This means, for example, that when we see surface or texture, we intuit depth, volume and weight. To draw something, then, is to think through materials to understand potential in imperceptible qualities of form, not just flat, inert surfaces. So drawing doesn't simply register something that is already there. "Field drawing," says Jon Clarke, "is a way of imprinting on your mind what's important." [Buzz Aldrin: How To Get Your Ass To Mars (Video)]

Of course, anytime you draw, the unexpected occurs.

I spent two hours drawing an outcrop that I thought might demonstrate the complexity of Summerville Formation and the Tidwell and Salt Wash members of the Morrison Formation.

The drawing was very dull — not even first-year art school standard, oh no. And although it would be better if I didn't post this drawing on this worldwide blog, today I am not feeling too proud. More importantly, failures in field drawing tell me much more about its value than successes.

It was only as we were leaving Box Canyon Quarry that I recognized something that I intuitively knew about my drawing from the very start. As we drove past the huge cliffs on our way back to the Mars Desert Research Station, I slowed the PEV and gazed up at the fluted columns of the rock face. For the first time, I could clearly see the thin horizontal beds of fine-grained clastic and evaporitic rocks, their intricate geometric patterns. And everything snapped into place. In proximity, I saw the detail of the cliff for the first time, and then I understood what I had been drawing.

Jon Clarke identified the outcrop in my drawing as incipient runiform landscape. He said, "What is most apparent from the sketch is its sedimentary architecture, its rhythmic cyclicity, which can be seen in three or possibly four similar cycles of sedimentary deposition. This kind of deposition is not necessarily evident in a photo. The average geologist would immediately be interested in the stratigraphic sections, the edges of the sandstone ledges and the thicker bedding."

What can't be seen in the drawing is the lithology. What rock types make this up?

Understanding lithology is tricky at any distance. "If you really want to know what you are dealing with, you need to scratch it or pour acid on it," Jon Clarke told me, "and nothing replaces direct contact." Thickness and height here in my outcrop drawing are unknown.

Today's field sketching test in the PEV reminded me of something else. After driving past the outcrop on the way home, I remembered how point of view and purpose in drawing are closely related. To position the cliff in my vision, I had parked the PEV smack in the middle of the quarry, mid-distance from the cliff face. Subsequently, I made another choice — to position the image of the outcrop roughly in the mid-ground of the picture plane. To find the mid-ground, our eyes measure distance from the foreground, where we can discern detail, back and forth to a vanishing point on the horizon.

Mid-ground is somewhere in between. As in space, a scale, human or otherwise, is necessary, especially in this enormous landscape where there is little vegetation.

I could have driven closer to see detail in a feature of the cliff, or I could have parked farther away to allow me to see more of the geological context of the outcrop.

Jon Clarke says that in geological field drawing, often it is the big picture that is missing. In this drawing of mine, one does gets a sense of the "objectness" of the subject and its location, but with little context or detail. To me, drawing the outcrop in the mid-ground feels picturesque. The outcrop is fixed, contained or held in place. There is no doubt that changes in scale change what is visible. Critically, it is important that choices in scale show processes that shape the landscape.

As the granularity of the field sketch for geology is significant in both determining location for the PEV and the position of the subject on the paper, the learning from this situation was evident. The mid-distance as a location for the field sketch provides neither detail nor geological context for field drawing, although it may provide some content — for example, in this case, stratigraphy.

In the same way that knowing chemistry isn't enough to understand mineralogy, drawing a field sketch can only inform field science. These preliminary recommendations about how a field sketch might function from the PEV tentatively address questions of scale.

If the purpose of the sketch can be defined, the researcher can commit in terms of locating the vehicle in relation to the subject so it can be seen within its geological context. This might mean moving in closer to see detail, or expanding the depth of field.

Perhaps it might be good to avoid the mid-ground.

And make sure you take plenty of lunch.

Editor's Note: To follow The Mars Society's Mars 160 mission and see daily photos and updates, visit the mission's website here: http://mars160.marssociety.org/. You can also follow the mission on Twitter @MDRSUpdates. For information on joining The Mars Society, visit: http://www.marssociety.org/home/join_us/.

Annalea Beattie is an artist and writer based in Melbourne, Australia, and her art practice is based on space science. She is a member of The Mars Society's Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analog mission, where her art-based research explores how observation is key to the role of all field geologists, including those on a planetary exploration crew. Follow The Mars Society on Twitter at @TheMarsSociety and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.